A Greek invention overturns technology history

By Peter Minturn

Photographs: Antikythera mechanism research project, Peter Minturn

Many years ago in a history of technology, I read a passing mention of a strange artefact, a piece of mechanical gearing, that was in the Athens National Archaeological Museum. I didn’t know then, but getting to see this would become an obsession in my life.

The artefact was recovered in 1900 from an ancient Greek galley. This ocean-floor wreck was accidentally discovered by sponge fishermen sheltering from a storm by the tiny island of Antikythera. One of the artefacts later taken from the ship was a corroded block of copper which, after it was cleaned, revealed the vestiges of a complex gear train. This has come to be known as the Antikythera Mechanism.

This story so captivated me I tracked down a complete book about this unique artefact. The author said that the complex gear train in this 2000-year-old piece of precision engineering was not duplicated in clocks until the 1750s. I promised myself if I ever went to Athens I would see this incredible monument to Greek civilisation and in my 70th year fulfilled this long-held ambition.

A lifelong study

Amazingly, the Athens Museum did not give this block of corroded copper the attention it deserved, despite disputing several times with academics that it was indeed as old as the wreck that dated from about 100BC. It was not until 1958 that Derek de Solla Price, an English physicist and Professor of the History of Science at Yale University, went to Athens to examine the mechanism. Its study consumed the rest of his life.

Writing in Scientific American in 1959, Price said: “The Antikythera mechanism must therefore be an arithmetical counterpart of the much more familiar geometrical models of the solar system which were known to Plato and Archimedes and evolved into the orrery and the planetarium. The mechanism is like a great astronomical clock without an escapement…”

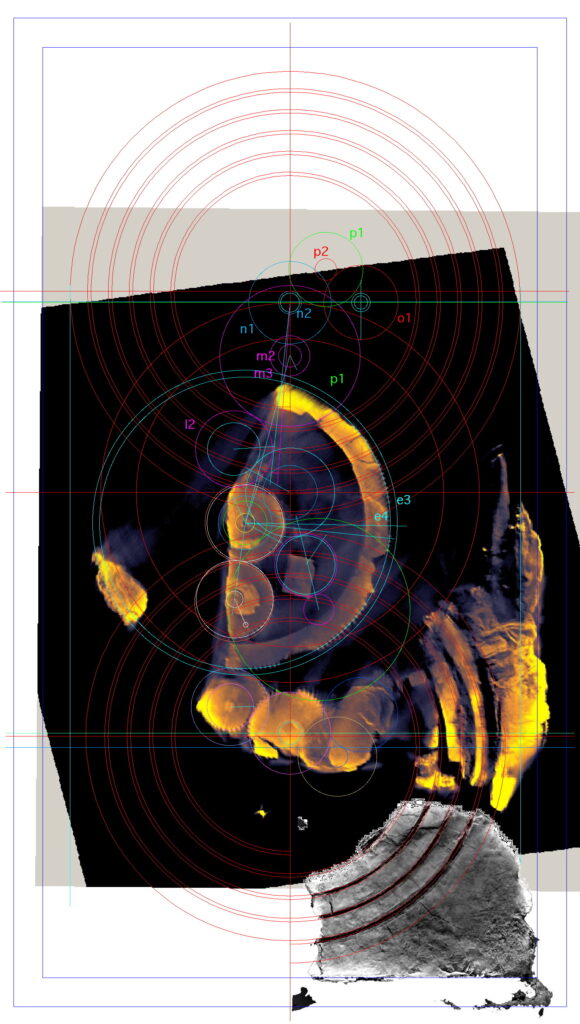

He described the front dial – “the only known extensive specimen from antiquity of a scientifically graduated instrument” – with its two scales, names of the signs of the zodiac and the months of the year. The two back dials with inscriptions were more complex. Using X-rays, Price suggested the inscriptions on the upper dial were the rising and setting of the five planets known to the Greeks (Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn), with the letters, number and lines of the lower dial recording sun and moon movements.

The book was my introduction

His book Gears from the Greeks was the little tract that introduced me to this incredible artefact. In it he wrote: “Nothing like this instrument is preserved elsewhere. From all we know of science and technology in the Hellenistic Age, we should have felt that such a device could not exist.” Price wrote later that the mechanism required a complete re-think on the history of technology. In Price’s opinion, “It must rank as one of the greatest mechanical inventions of all time.”

In June this year, my wife and two English friends spent two weeks in Greece. On a hot afternoon while everyone enjoyed a siesta, I took off to the Archaeological Museum’s air-conditioned concourse. I asked the young woman behind the reception desk if she spoke English, telling her I had come 12,000 miles to see the “gear train from the Greeks.” She told me without hesitation the exact hall and display case number where I could find it. Surprisingly, the Athens Museum still does not rate this artefact as sufficiently important to include it in its current guide.

First view

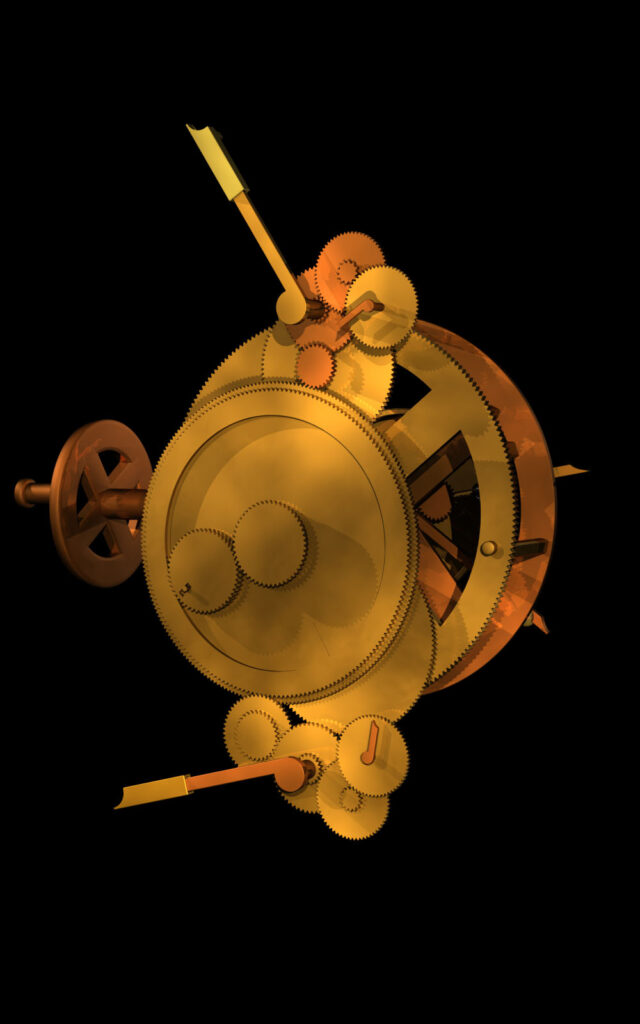

Passing the treasures of Ancient Greece without a second glance, I went directly to the hall and there it was. It’s a blob of corroded copper about the size of a CD and the thickness of a large paperback novel, sitting majestically in a case of its own in the centre of the room. And yes, you can clearly see the cogs. Beside it sits a modern model, as it would have looked 2000 years ago.

As I was studying this surprising piece of ancient shed work, an American asked me what it was. When I explained, this guy was enthralled, realising this block of corroded copper summed up a remarkable collection of knowledge and technology.

The people who designed it had to have the astronomical knowledge the device was built to predict. They had to have the ability to turn that knowledge into a mathematical equation reflected in the device’s gear ratios. They then had to find some ancient sheddie with the engineering skills to make this gear train (there were no toolmakers or clockmakers in ancient Greece, as far as we know). A gear train that was not re-invented for centuries.

What the American and I did not know was, since I had read Price, another chap who worked for the Science Museum in London also became hooked. Internet research reveals his name is Michael Wright and he was responsible for restoring old clocks at the museum.

He became obsessed

After Derek Price died in 1983, Wright’s studies revealed that Price had made some fundamental errors. Price had approached the mechanism from a purely theoretical viewpoint, whereas Wright could see from his knowledge of clocks that Price’s conclusions on the device’s purpose did not match up with the gear trains he had predicted were inside.

Wright became so obsessed with the study of the mechanism, and the fact that the Science Museum would not let him work on it in their time, that on every available leave he would take off to Athens to study the artefact to a point where his obsession cost him his marriage.

The Science Museum and the Athens Museum did not know that Wright was building a replica in his “shed”. As Wright began to document his work for publication he learnt that the Athens Museum had contracted to have the mechanism X-rayed with the latest CT (Computer Tomography) machine known as the Bladerunner, made by a company called X-Tek.

Exceeded all expectations

Wright regarded the artefact as his own by now and has written that he was beside himself with anger. Despite this, he turned up when they hauled the 7.5-tonne machine into the museum. They expected to be able to see the teeth of the gears hidden in the mass, but the machine exceeded all their expectations when it revealed that on some of the gears were engraved words like COSMOS and SPHERE. On one dial was engraved “235 divisions on spiral” which confirmed Price’s theory that the machine was geared to replicate the Metonic Cycle (after Meton of Athens) of 235 lunar months. One of the Greek translators said it was as if the manual for the machine had been built into it.

This machine was able to duplicate all the astronomical knowledge of the Greeks. The knob on the side, when turned, would have engaged the solar gear which in turn drove other gears that moved the day-of-the-year pointers, and the lunar and planetary gears would trace eccentric orbits, sometimes reversing much as planets appear to do in the sky.

As for the Athens Archaeological museum, maybe one day they will feel as fond of this blob of copper as they do about the golden mask of Agamemnon. As a goldsmith, I can appreciate the beauty of this and the other splendid gold works in that museum, but from an intellectual level, compared to that blob of corroded copper, the gold works are just kids’ stuff.

* For more information: http://www.antikythera-mechanism.gr

Signs

Interpreting signs is part of the detailed, shrewd analysis that is uncovering the secrets of the Antikythera Mechanism. Nature magazine in November 2006 reported that among the glyphs or sculptured symbols on the mechanism are the Greek capital letter sigma (Σ) and the Greek capital letter eta (Η). Sigma (Σ) stands for lunar eclipse, from the Greek word for moon, selini (ΣΕΛΗΝΗ) and eta (Η) means solar eclipse, from the Greek word for sun, (h)elios (ΗΛΙΟΣ).

The letters are also important for authenticating the date of the mechanism. Nature reported Haralambos Kritzas, director emeritus of the Epigraphic Museum, Athens, saying the style of the writing could date the inscriptions to the second half of the second century BC. Some examples: Σ sigma has the two lines not horizontal but at an angle, Y upsilon has the vertical line short, Π pi has unequal legs, Θ theta has a short line in the middle, in one case a dot.

What it does

In the article, “Decoding the ancient Greek astronomical calculator known as the Antikythera Mechanism” in Nature, November 2006, the 17 authors described the Antikythera Mechanism as “a unique Greek geared device, constructed around the end of the 2nd century BC. It is known that it calculated and displayed celestial information, particularly cycles such as the phases of the moon and a luni-solar calendar…” The magazine reported that surface imaging and high-resolution X-ray tomography of the surviving fragments enabled the authors us to reconstruct the gear function and double the number of deciphered inscriptions. The mechanism predicted lunar and solar eclipses on the basis of Babylonian arithmetic-progression cycles. The inscriptions support suggestions of mechanical display of planetary positions now lost.