A set of modular rolling cabinets make space in the garage

By Jude Woodside

Photographs: Jude Woodside

The first law of shed dynamics is: The need for shed space will always grow to exceed the space available. For some reason, women seem pre-programmed to believe that a garage is intend to house a car, whereas we know that the only time a car should be found in a garage is when it needs some work.

With space at a premium, it is incumbent to make the best use of it. So I evolved an idea for a modular set of moveable cabinets that could be rolled out for each job and configured as required. It means I could easily house my commonly used tools and still retain space in the shed.

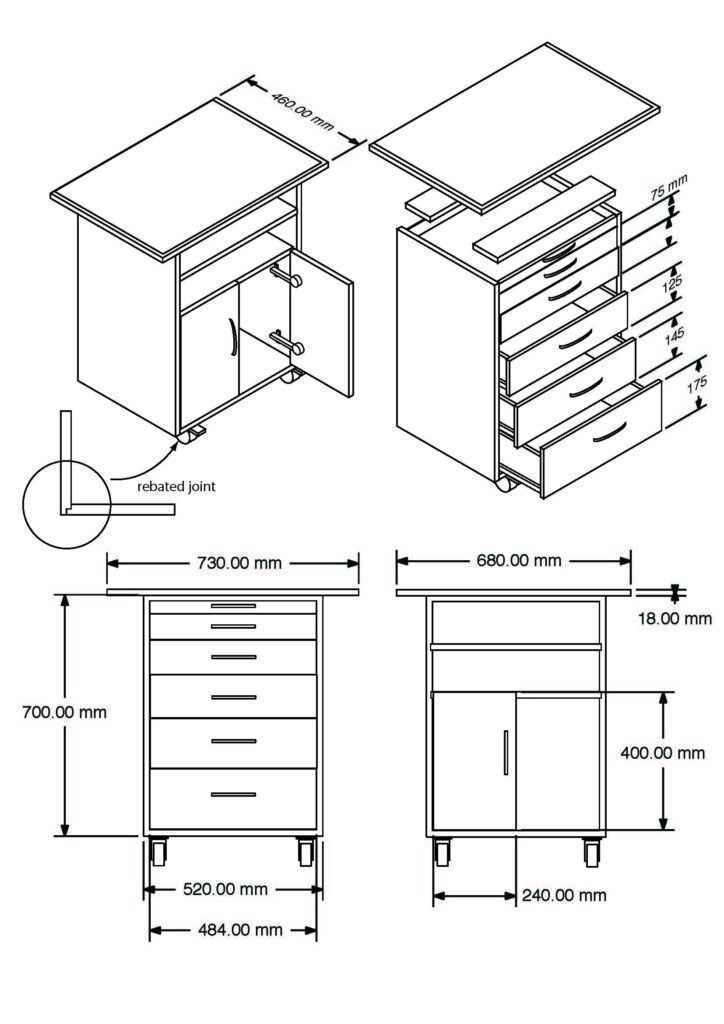

Each cabinet was built from 18mm C-D ply, which may appear like overkill but you can never be sure what use each cabinet may be put to outside of carrying tools. It is easy to underestimate the weight of a cabinet full of tools. The sides top and bottom are 18mm and back is 4mm ply to help it all align and strengthen the carcass.

C-D grade is construction grade ply and often has gaps in the plys. This is usually not a concern and the carcass can be edged with timber or veneer at some later stage.

Castors

The cabinets run on 63mm castors for which the front two lock and the rear are fixed. Beyond this each box can be configured to suit. Some have drawers others shelves and doors or a mixture of each. The tops overhang the cabinets and have clashing on the front and sides to prevent the ply splinters catching on fabric.

It’s best to plan in advance which cabinets will have drawers; the layout of the mounting holes for the drawer glides is so much easier when the cabinet is in pieces. It can be done after assembly but it’s awkward and usually inaccurate.

To lay out the drawers I have used a simple progression formula. This is based on establishing a couple of parameters to allow the dimensions to be worked out. A graduated system does allow for a better look, even in a workshop cabinet. It permits a better balance by keeping the heavier things on the base.

I designed these to suit my way of working so the cabinet tops stand 815mm off the ground and are 450mm x 700mm in one case and 450mm x 500mm in another.

The wheels are 95mm high and the top is 18mm thick. That leaves the actual length of the sides as 700mm x 400mm.

Cutting

First cut the ply to size. To save time and frustration, I have the supplier cut the pieces to size. It is worth remembering the way the grain runs in plywood too and cutting the piece to maximise use of the grain. It is possible get sufficient material from one sheet for two cabinets of this size. Any waste will make up the cross pieces, doors and shelves.

The rear of the cabinet is a 4 mm piece of ply, MDF or particle board. Ply is the most durable and this is simply slotted into a 4mm slot that is trenched on the rear of the components. It serves to align the pieces, keeping the whole square rather than contributing any structural strength.

First, sort the pieces as they come from the supplier. Work out which pieces are for each cabinet, selecting the outer and inner sides, (although this is only for the workshop it is still good practice to keep the better, long sides on the outside for appearance).

Cut the rebate for the connection. I rebate both the sides and the bottom so that they present the largest possible area of contact for gluing and the joint itself adds some rigidity to the construction. It’s not strictly necessary and since we are using polyurethane glue and screws a butt joint would be fine and save time. But I find the rebate helps in assembly, which I normally do single-handed.

Trench

Cut a trench 9mm deep 9mm from the edge on both ends of the bottom and sides. I also cut some scrap pieces that will serve as cross pieces on the top to hold the tops in place, too. Cut a 4mm trench for the top on the back edge of the two sides, the bottom and one of the cross pieces.

I usually do this on the saw but it would probably be quicker on a router. Setting up my router takes more time than I like (a new router table is the next project).

It helps to mark the backs on the sides in particular so you don’t inadvertently trench the wrong side.

Next mark up a template for the placement of the drawer runners. This will serve both sides. Mark the rear and front edges on both pieces and clearly mark the side (left or right) and the front or rear on the template. Mark the corresponding side on the other side of the template too. This saves a good deal of confusion and eliminates error.

Lay out the drawer runners on the top of the template in the order you want them. Mark and drill the pilot holes for each runner. Flip the template and drill the pilot holes on the opposite side.

Attach all the drawer slides. These slides can also be used for sliding shelves. Fixed shelves are attached via trenches.

Drawers

The drawers are constructed in a utilitarian fashion, using the simple box glue-and-screw construction. Make the false fronts from the leftover 13mm material. The drawer slides are attached and the false front screwed into place. If you are using a ply with a timber face that will not be painted, cut the material for drawer fronts last so the material presents a consistent grain pattern.’

The handles were the cheapest available at the bulk store closest to me and selected on the basis that there were not protruding parts which could conceivably catch on clothing. As they cost around $2.30 each, I was able to secure enough for the door handles too.

Assembly

Begin the assembly by gluing the sides to the base and inserting the backboard. Screw the sides to the base to hold it until the glue sets. Similarly glue and screw the cross pieces in place. The backboard helps to ensure that all the pieces are square and housed. It helps enormously with locking all the elements in place while you set up clamps and establishing square is far easier.

Second cabinet

The second cabinet has shelves and doors to hold larger power tools out of sight. The sides are trenched and the shelves are fitted in place and glued and screwed. The lower shelf is set back a little from the cabinet front edge via a stopped trench to allow the doors to close flush with the cabinet side.

I opted for hidden hinge hardware here to avoid the need for clips and other door closing hardware. The hinges are placed into a 32mm hole cut in the door with a Forstner bit. Accuracy is vital although there is some scope for after-fitting adjustment.

With the cabinets assembled, it is now a good time to fix the castors. With the cabinets upside down, mark the position of the front castors allowing sufficient overhang for the locking mechanism to protrude to be easily foot-operated.

Lessons

Lesson No 1: Every brand of caster will vary and it pays to check on the overall height of the castors. My first lesson was that fixed castors and lockable castors, even of the same brand and wheel size, are not the same depth. It required that I add spacer blocks to the fixed castors at the rear to keep the top parallel to the ground.

Lesson No 2: if I was doing this again I would use a swivelling castor on the rear too. At the risk of handling like a supermarket trolley it does make for better manoeuvrability. The fixed castor is more restrictive than I had anticipated.

The tops are 430mm x 700mm and 430mm x 650mm. The fronts and sides are clashed with solid timber (15mm). I prefer to use biscuits where I can to attach these. They help to hold the piece in place while it sets.

Tops

The tops are designed to be removed to make them more useful. They are also intended to be butted together to make a larger working area if needed. The tops could be faced with laminate, leather or sheet metal depending on your needs. I have rounded the corners on the front edges, again to avoid catching passing clothes etc. and the edges are all smoothed off with sandpaper. It might be an idea to face the edges with veneer at some later time and finish with polyurethane to keep them clean.

Next stage is to make cabinets for the mitre saw and a dedicated router stand. But that’s another project.