A sheddie’s extraordinary collection of objects gives a vivid snapshot of bygone eras

By Nathalie Brown

Photographs: Derek Golding

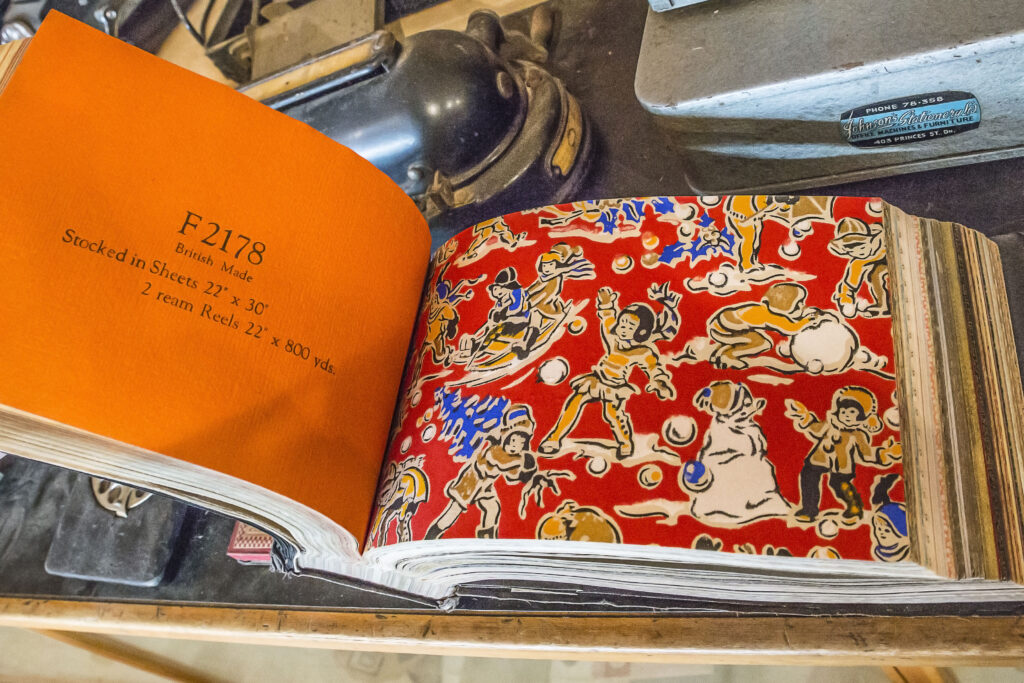

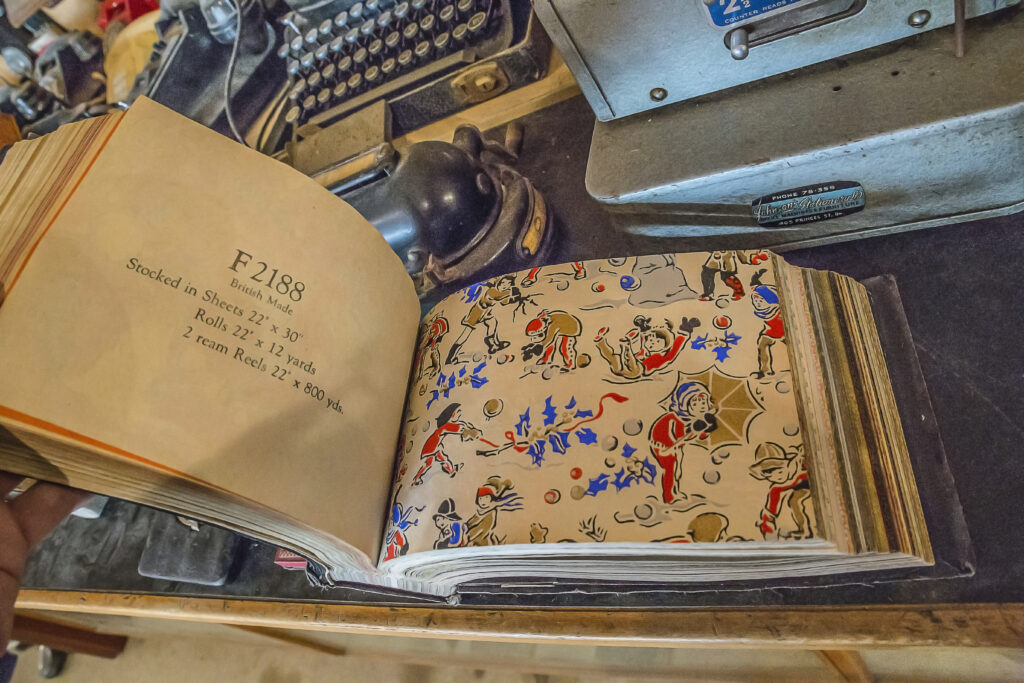

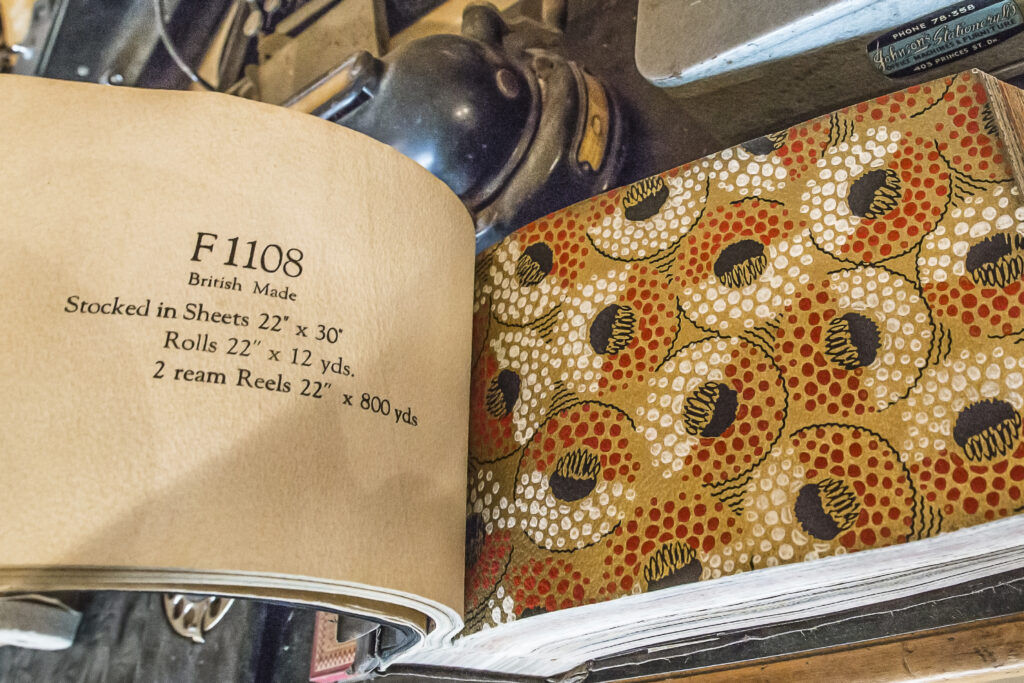

It started with a teddy bear, then an American Greyhound bus, a wind-up Sherman tank and an aeroplane. Alastair Allan held on to his toys long after others would have put them aside. He’s still got them, along with several thousand other items that he has bought or acquired over the past 70 years or so. He declares he is holding on to the past for the future to tell the story of how people lived in North Otago as far back as 150 years ago.

Born in Oamaru in 1934, Alastair spent his first five years with his parents at the Loman Run, a grazing property of just over 3,000 acres at Kauru Hill in North Otago.

“It was quite well known around North Otago at the time – still is to this day,” Alastair muses. “My grandmother drew it in a ballot in August 1914 just as World War I broke out.”

He recounts the family story of how, in 1916, they put a house, a woolshed and a hut on the run.

“They were built by Craig and Co from Oamaru and transported by Maheno transport who had to take the materials on a traction engine and trailer and unload them a mile away from the house-site because the formed road stopped there. For that last mile or so it had to be sledged in. The buildings were the typical weatherboard with an iron roof.”

Before moving to the Loman Run Alastair’s paternal grandparents owned the Palmerston Hotel and had previously owned hotels all over the South Island.

In the late 1950s, after Alastair married Margaret Gray, he bought a poultry farm about 7km from Oamaru with 600 hens, and built that up to around 3500 birds.

Special inheritance

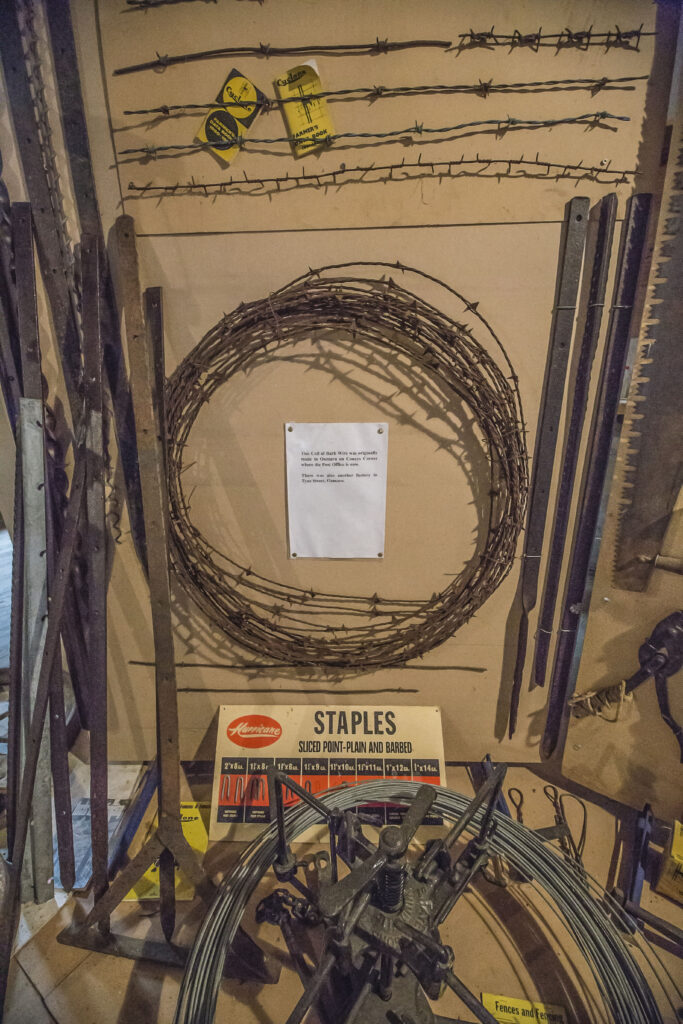

Around the same time, he inherited a lot of equipment relating to farming in general from the run – horse gear, sheep brands, drenches, and the like.

A member of a vintage car club and vintage machinery club, he acquired old vehicles and their parts. He added to his hoard by visiting clearing sales and second-hand shops, while people who knew he was interested in anything that reflected the (mostly rural) past would donate items they no longer wanted. Even after the advent of TradeMe Alastair never bought anything on-line. In the early days, he stored all his finds in sheds on the poultry farm.

Margaret died in 1990 and six years later he married Dolina Hill who became familiar with what was in the sheds and makes all the labels for what she wryly calls ‘Alastair’s junk’.

When Alastair retired from poultry farming in 2001 he cleaned out the two poultry sheds (24.5x8m and 14x12m) and the 15x8m feed shed he had built in the 1950s before installing his vintage tractors and machinery. He began mounting displays and over the years people came to visit in organised groups and occasionally as individuals.

The pleasure in collecting, he says, is being able to tell people what things are – holding on to things from the past for the future.

Historic displays

Several of his displays are now housed in Whitestone City, the tourism attraction in Oamaru’s historic precinct. The grocery store, pharmacy and most of the barber’s shop there came from Alastair’s sheds.

The grocery store carries a wall plaque to recognise Alastair’s contribution to the tourist attraction: Alastair Allan General Store – Local man Alastair Allan has been collecting items from the local community for over 60 years and we are proud to show in these shops the highlights of his collection.

The shelves of the store are stacked with boxes of Huntley and Palmers Cheesals, Rickitt’s Bag Blue to brighten laundry whites, Ipana Toothpaste in the bright yellow and red tube; tins and boxes and bottles of baking ingredients… you get the picture. There’s a smart black coffee grinder, a broad display of large biscuit tins, tea caddies, bottles of fruit cordials. And there’s more…jars and bottles and thermos flasks. Tintex Makes Home Dying Easy. Old-fashioned milk bottles, tins of Edmonds Acto Cake Baking Powder and Andrews Liver Salts.

There are stacks of beautiful honey tins from regional apiarists – The Glass Bros., No. 5RD Gore; the Wilsons at Elderslie, Oamaru; R.D. Benny in Central Otago, and R.W. Marshall of Hampden, North Otago.

Many of the items in the displays are faded, foxed and rusted but that makes them all the more attractive than anything that might have been recently replicated.

The Chemist Shop has display cabinets full of little flat boxes and tins which anyone from the ’40s to the ’70s, will recall. There is a display of little implements, glass bottles, and instruments from a bygone era for applying leeches; a “breast reliever”; and a selection of ferocious-looking metal grips and plungers with faded red rubber tubes, seemingly the parts of a collection of medical syringes. Other items in the displays were sourced from the Pharmacy Guild.

Distinctive collection

The Barber’s Shop & Tobacconist was largely supplied by Alastair: brushes, combs and clippers, bottles and jars of styling lotions and cremes for the discerning gentleman; bone-handled cut-throat razors, razor strops, things that look like early era curling tongs. Little leather manicure sets with ivory handles. A folder full of black and white photographs of the Brylcreme Style of the Month for junior, mature and senior men. Another cabinet holds an array of tobacco products in a distinctive array of tins.

The vehicles, machinery and implements in the Whitestone City agricultural display came from Alastair’s sheds and still, you can barely see a gap in his home displays.

A couple of small private museums have also acquired items for their displays but there are still thousands of items yet to find a new curator.

Says Alastair. “Most of it has come from around North Otago and it would be nice to think it would stay here.”

Gear and gizmos

The uses of these gizmos would baffle most baby boomers let alone millennials but Alastair usually had a good idea of what they were used for because they were often from his era. But in the early days, when he first began collecting, there were folk three and four decades older than he was and they were able to tell him what was what.

The much sought-after Beattie washing machine relieved women of the hours it took to do the laundry

Other display areas are devoted to kitchen utensils: grinders, peelers, mincers, egg beaters, irons, a flour bag collection, blue-and-white enamel ware, cardboard imitation Willowware

Mops, brooms and carpet sweepers have their own nook in one of the sheds

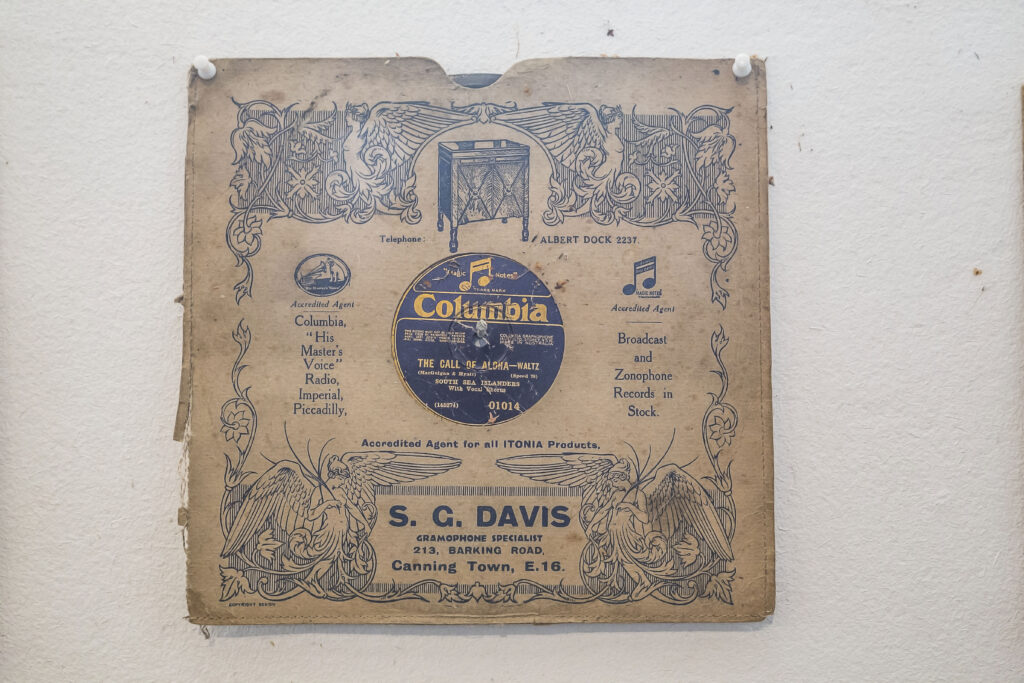

Gramophones galore!

Another display is devoted to the mechanisms for making dairy products: butter churns, a butter conditioner to extract the butter milk. And a pump to save the day when guests arrive for a plate of scones or pikelets with cream and jam but: “Blow it, I’ve run out of cream.” Pop a pat of unsalted butter with a splash of milk in the receptacle, give it a vigorous pumping and hey presto! “You can hardly tell the difference from fresh cream,” says Alastair. It’s called a Bell Cream Maker

The medical instruments for treating animals are terrifying. The stomach pump (don’t even think about how that worked) and drench guns circa 1840 for horses belonged to Alastair’s grandfather

A seal skin rug covers your legs while you take a ride in the open carriage

Alastair has a shed full of farm vehicles including a 4WD Massey Harris tractor, and the second oldest Fordson in New Zealand – a 1918 model. The tractors are in running order but cranking them is beyond Alastair’s strength these days.

Here is a video of Alastair giving us a tour of his shed.