Knowing how to use dies and taps can be a useful skill in the home workshop.

By Bert Toomey

Photographs: Gerald Shacklock and Bert Toomey

From time to time in the home workshop, you may need to make a new threaded hole for a bolt and create the threads on the bolt itself. It’s handy to know how to use the dies that are rotated onto a bolt blank to make these threads, and to know how to use the taps that create the threaded holes. This skill will be especially good for those interested in model engineering, go-karts or light engineering, but who have not been trained in the use of hand tools for making threads.

There are many different thread sizes. These are made to international standards. In all cases, the size of a thread eg, 6mm or ½ inch and so on, is determined by the diameter of the rod or bar on which it may be cut.

DIES

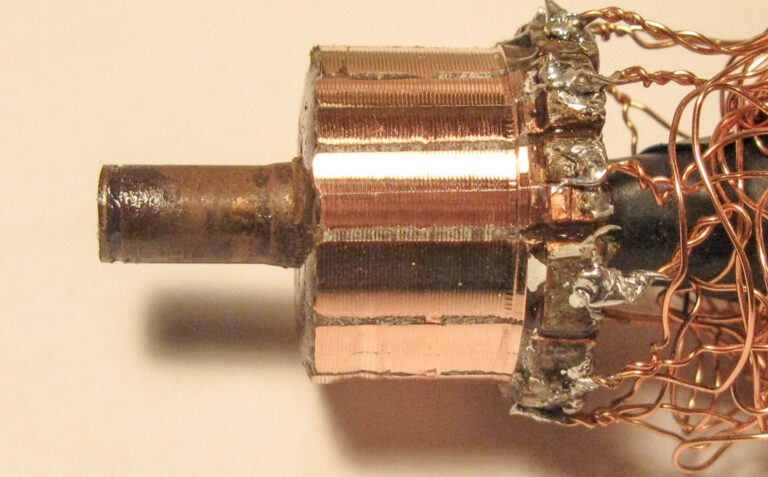

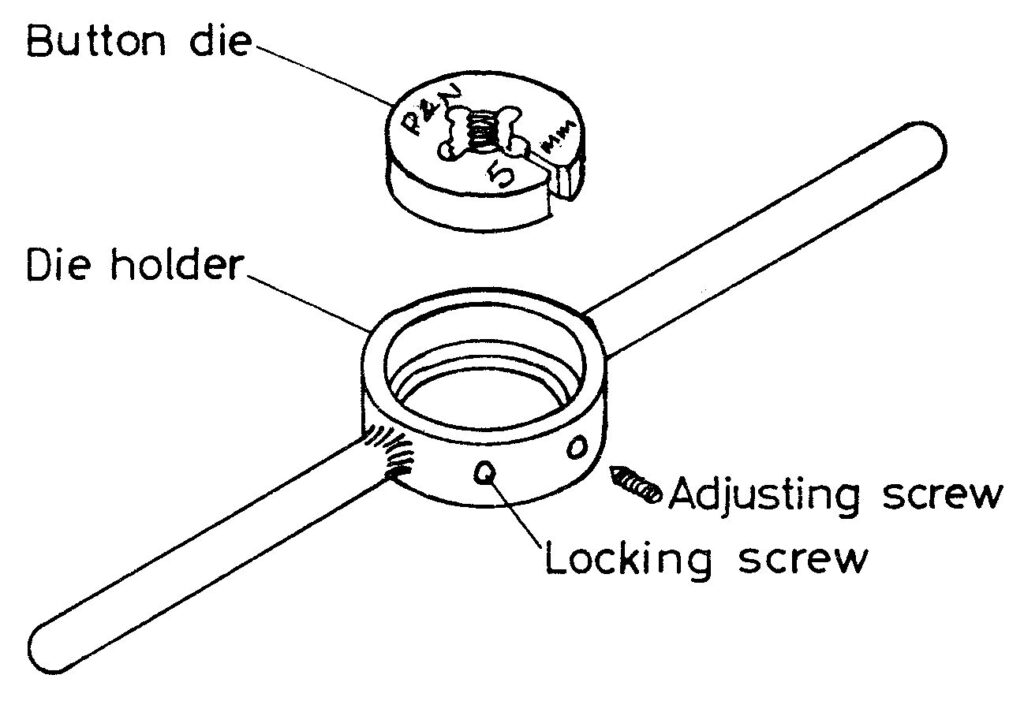

External or male threads are cut with dies. Some types are called circular split dies. The split enables the die to be adjusted to the correct size. FIG 1 shows one of the smaller varieties, sometimes called button dies. There also dies which are made in two halves, the holder fitting into a two handled stock. All dies have the size stamped on them. For circular dies, this is USUALLY the starting or relieved side, and should face DOWNWARDS when in use, enabling the die to start cutting.

Some sets of dies have guides for each size of rod. To make “starting” easier, the end of the rod should be chamfered at an angle of approx 45°. This may be done on the grinder or by filing in the lathe.

Hexagon die nuts are also made in standard sizes. These should be used to recut a damaged thread or finish a thread cut on a lathe.

USING DIES

With the rod held in a vice, apply the starting side of the die to the chamfered end of the rod, applying a downwards pressure. To start, turn the die clockwise for two or three turns and then reverse for half a turn. From then on, turn the die about three quarters of a turn and then reverse for half a turn. This action clears the swarf from the work and is repeated until the required length of thread is obtained.

If you continuously rotate the die, this will often strip the thread due to a build-up of swarf. For thread diameters in excess of 12mm, it’s best to set the dies oversize and take several cuts. Some lubrication should be provided. A light oil is suitable in most cases. The smaller range of circular split dies has no guide bushes. Starting these square with the rod can be a problem, and setting the die in the lathe drill chuck may help.

TAPS

In engineering terms, taps are the tools used to cut threads inside a hole. Tap design has kept up with the ever increasing range of materials that are available and of course advancements in CNC technology and machines which are very demanding on cutting tools. While this is great for the high tech guys with their fancy machines it also has benefits for those of us cutting threads at home. There are application specific products available to do just about any job in any material we need to thread, but the three most common types that we are likely to find a use for in our sheds are; Hand Taps (otherwise known as straight machine taps), Gun Nose Taps (otherwise known as spiral point taps) and Spiral Flute Taps.

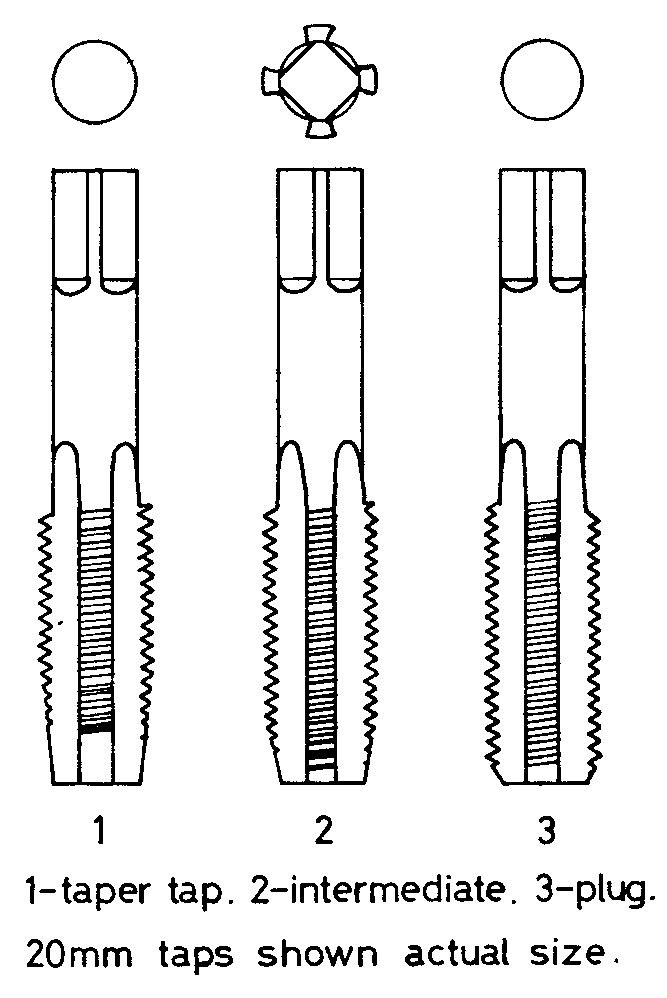

Hand Taps are made in sets of three, called taper, intermediate and plug or bottoming tap, as illustrated. These are a general purpose tool suitable for hand or machine tapping and as a general rule can be used for threading holes up to 1.5 x diameter i.e. 8mm tap will tap up to 12mm deep.

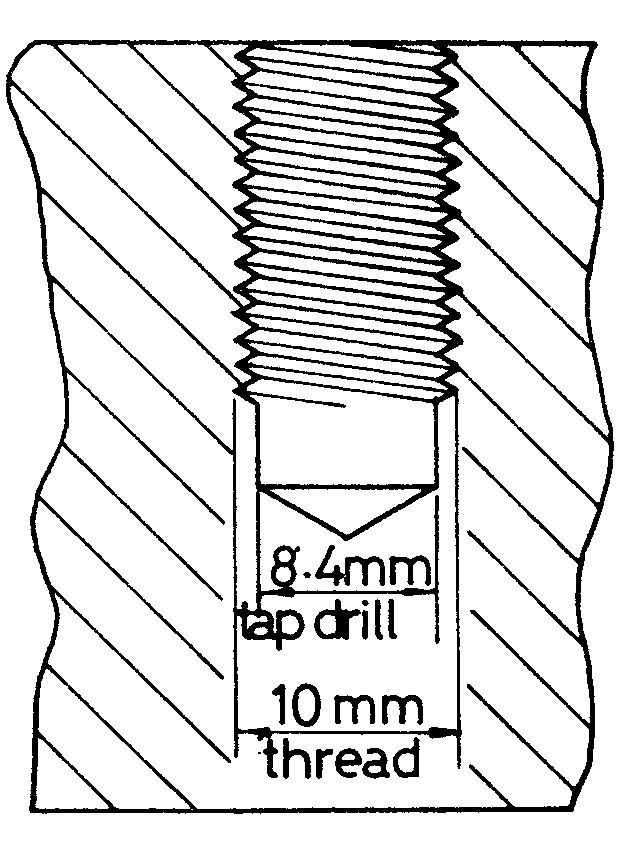

The hole to be threaded has to be smaller in diameter than the thread size.

Sometimes the tapping drill size is marked on the tap but the best idea is to get hold of a set of engineer’s tables. A cheats guide to selecting the correct drill size for 10mm x 1.5mm tap is – Tapping Size Drill = major diameter – pitch or 10mm -1.5mm = 8.5mm, remember this is just a good guide, the best thing to do is ask your local Engineering merchant for a wall chart, most will supply you one for free.

USING TAPS

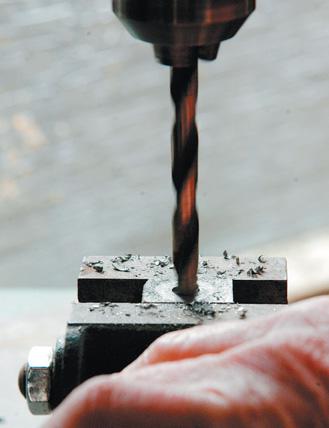

The technical term for cutting a thread inside a hole is called tapping. The technique is similar to that used for dies. The taps are gripped with a tap wrench (using an adjustable spanner is not recommended) and turned clockwise to get the tap started.

This is where things can get tricky. Taps are made from lots of different materials but the main ones we come across are likely to be HSGT (High Speed Ground Thread). This doesn’t mean run them as fast as possible, but refers to the raw material which is a tough high speed steel. These are the biggest selling range in NZ and the design of most manufacturers has improved dramatically in recent years. The other is carbon steel which is the cheaper material used to make most of the taps that we were taught with at school, polytechnic or as apprentices. Carbon steel taps are not relieved and are not as tough as HSGT taps. This is why we were taught to regularly reverse the taps to break and clear the swarf. This is still the case with carbon steel taps which should be reversed frequently, particularly in the case of “blind” holes.

HIGH SPEED STEEL

Now, when we use the modern design HSGT hand tap it is a very different story. The geometry is relieved and they are made from a much tougher material (high speed steel). The relief means the taps can be used by hand or for machine tapping and you don’t have to reverse the tap all the time to break the chip. In fact you must resist the temptation to constantly reverse the tap as the chip can damage the tap when you reverse.

Hand taps, either Carbon or HSGT come in three different leads, the TAPER tap is used first, which starts the thread, the INTERMEDIATE is used next and the PLUG tap cuts a full thread to the bottom of the hole.

Gun Nose taps (Spiral Point Taps) are primarily designed for through holes however they can also be used in blind holes if there is ample clearance at the bottom of the hole to accommodate the chips/swarf. Gun taps have angular cutting faces at the point which forces the chip forward. This means they are tougher than hand taps due to the shallower flutes allowing for a stronger cross section. The cutting action should be continuous with no reversal until the full depth has been reached. They can be used in either machine or hand applications.

Spiral Flute taps are designed for machine use and primarily for blind holes. As the name suggests they have a spiral flute similar to that of a drill bit. The shear action of the spiral flutes draws the chip out of the hole which allows greater depth of threading without chip clogging. They are used to the best advantage in soft material, like mild steel or aluminium that produces long string chips.

Some taps have a centre hole in the end of the shank. This enables the tap to be guided when you are threading holes in heavy work e. g. large castings. Figure….shows how this centre may be used to advantage. Provide lubrication, except for cast iron which does not need it. Taps and dies are available to cut both right and left-hand threads.

* Additional information supplied by Kevin Donovan, General Manager, Patience & Nicholson (NZ) Ltd.