Handy stools for bar or kitchen are enhanced when built in macrocarpa

By Vivien Edwards

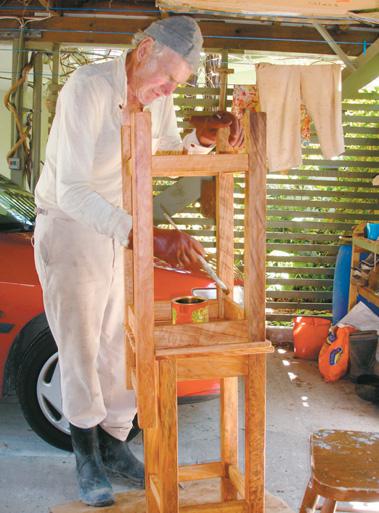

Circular saw noises drift up from my neighbour’s shed to my office, and I know that John Ellery is busy at work making useful wooden objects.

He creates indoor and outdoor furniture using native and homegrown timber sourced from the family farm at Arohena in the Waikato. Ata, his wife, a contemporary artist, keeps a watchful eye on his progress, but at a respectful distance. John works in a shed that is not untypical.

It is a 2m x 3m cubicle with a small window, narrow benches and shelving, situated at the back of the double carport. He does what he can in the available space, which he also shares with a fridge. He uses a portable workbench and spreads his work out when necessary into the carport. The all-purpose carport is also host from time to time to home-grown produce – a bunch of ripening bananas from John’s garden, a net bag of walnuts drying, macadamias or a string of red onions. Sometimes, the tools and work have to spread beyond the carport. To make working around the cars easier, John built an extension into the side of the carport, giving himself more bench space and additional shelving.

He added a window to improve the lighting. In this area, he has made large, rough-sawn outdoor

macrocarpa garden seats, a bird house and the macrocarpa bar stools which he describes here and

which were requested by his son Ian.

The plan

From macrocarpa sections, I cut out the rear legs (45 x 45 x 750mm), front legs (45 x 45 x 610mm), top rail for the back support (60 x 15 x 290mm), front and rear supports for the seat slats (65 x 18 x 290mm), the side-rail seat supports (45 x 18 x 250mm), the front and rear lower rails (45 x 18 x 290mm) and two side lower rails (45 x 18 x 250mm). The two seat slats which sit on the side seat supports are cut at 45 x 15 x 270mm, while the five seat slats in the middle are 45 x 15 x 370mm.

I use dowelling for ease of construction, measuring and cutting as I go, and joining them to the stool with PVA glue. Place the dowels off-centre on the end of the rails, to avoid hitting the dowels coming into the legs at right angles.

The front and rear sections of the stool are put together separately then joined. The slats for seating

are then assembled, working from the outside into the centre. The finished stool is dressed with a raw beeswax, natural turpentine and raw linseed oil mixture. To build a stool with no back, make rear legs the same measurements as front.

Cutting

I use 50-year-old macrocarpa which I find is not the easiest timber to work with, as inner tensions cause it to spring and to curve.

First I cut the legs to size – you can often get two legs out of a piece of rough stock and sand the saw marks off them. Then cut the front and rear seat supports to which slats will be secured. Mark a curve in the top of the seat supports, to a maximum depth of 15-20mm. This will create a more comfortable seating base when the slats are on.

I clamp the seat supports together and trim out both curves identically with a rasp.

Front and rear

The first section to be assembled is the back. The two rear legs are connected by the top back rail

(25mm from the top of the rear legs), back seat support (140mm from the top of the legs) and

bottom rear rail (150mm up from the bottom of the legs). I mark the outer edge of the rails 12mm from the edge of the legs. Before connecting the rear seat support to the legs, be sure to drill the five evenly spaced dowel holes in top for the seat slats. Once the top rail is on, there is insufficient room to use a drill. I attach a collar to the drill bit to control the hole depth for the dowels.

Assemble the front section in a similar way, with the front seat support flush with the top of the

legs, and the bottom rail 150mm from the bottom of the legs, and 12mm in from the edge. The front and back sections are joined with the seat-support side rails flush with the top of the front

legs, and the lower side rails parallel with the lower rails at the front and rear. Use a rule and set square to measure up the exact location for the front and back sections. I use dowel markers placed in the holes drilled in the end of the rails to help pinpoint where the dowels go. The spike on the buttons is imprinted when the rail is set against the leg and given a light tap.

Joining

When joining front and rear sections, lay the back section on the bench, glue the dowel holes and insert the leg dowels all the way home. Glue up the rails and apply glue to the face of the leg where the rail will meet it.

Now fix the rails onto the dowels, glue and insert dowels into the end of the rails and then manoeuvre the front section on top of these dowels. Hammer evenly and gently around the front section, using a wooden block to protect the legs. Stand the stool on even level surface to see it

is sitting square, and clamp it until the glue dries.

Seat slats

Ease the edges with a slight chamfer by lightly planing and sanding.

Chamfer the end grain on the tops of the chair legs with a sharp chisel. I also round off the edges of the wooden slats before applying them. Drill five, evenly spaced dowel holes for the seat slats in the top of the front seat-support rail. In the slats themselves, I drill three holes for dowels in the slats which sit on the outer seat supports (matching two holes on the rail and one on top of the front leg), and two dowel holes at either end of the five slats in the middle of the seat.

Place the outside slats first, and work towards the last slat at the centre. As can happen with macrocarpa, one slat in the stool I made had sprung a curve, and needed clamping to secure it in place.

Dressing

When the glue has dried, dress the finished stools with a mix of raw beeswax, natural turpentine

and raw linseed oil (see recipe).

At first, I fi nd it pays to dress the wood every 2-3 hours, then twice a day, then once a day for a month until stool will not take up any more dressing. From then on, only occasional touch-ups are required when the wood dries out.

CUTTING LIST FOR BACKED STOOL

2 rear legs 45 x 45 x 750mm

2 front legs 45 x 45 x 610mm

Top rail for seat back 60 x 15 x 290mm (25mm from top of rear legs)

Front and rear seat supports 65 x 18 x 290mm (curvature 15-20mm in centre)

Front and rear rails 45 x 18 x 290mm (connecting legs 150mm from bottom)

4 side rails 45 x 18 x 250mm

2 seat slats 45 x 15 x 270mm (on side seat supports)

5 seat slats 45 x 15 x 370mm

ASSEMBLY

4 dowels 6 x 40mm (Top rail for seat back)

16 dowels 8 x 40mm (front and rear seat supports, seat side rails)

16 dowels 8 x 40mm (lower rails)

16 dowels 8 x 20mm (to attach seat slats).

PVA glue

FURNITURE DRESSING (ENOUGH FOR TWO STOOLS)

Raw linseed and raw beeswax give a more golden colour than refined products, and raw beeswax is around a quarter of the price. Natural turpentine is available through some art outlets. I have tried substituting mineral turpentine, but it was too oily and proved unsatisfactory.

100ml raw linseed

240ml natural turpentine

12gm raw beeswax

Melt the beeswax in warm linseed oil over hot water.

FROM FARM TO TIMBER

John’s relationship with wood goes back to his education at Takaka District High School, where

woodworking classes were held once a fortnight. At Massey College (which later became the University) he gained a Bachelor of Agricultural Science, majoring in dairy manufacturing.

He met and married Ata at Te Awamutu, and went into partnership with Ata and her brother Jay on the family farm at Arohena. Tradesmen and contractors were hard to come by because of the

distance from town, so developing do-it yourself and No 8 wire philosophies were a natural progression.

As part of his degree, John learned welding and brazing, useful around the farm for manufacturing metal trusses, sheep pens and turning pipe into gates. He was responsible for the stock and worked with sheep, cattle, deer and goats, improving their health and birth-rates. He increased lambing percentages from 95 -140 percent after making the sheep an easy-care flock. The sheep bought from Feilding-favoured flat land and could not deal with hill country, which was a prime factor in leading John to develop his own breeding programme.

There was little or no time then to create objects from wood, but planting and nurturing trees was

part of farm development. Eventually, the original 500 acres became 2500 acres through the

acquisition of run-down adjoining blocks. John and Ata collected small trees from felled areas and planted them out to increase the native bush area, which now amounts to 500 acres, and adjoins 1500 acres of native Department of Conservation land.

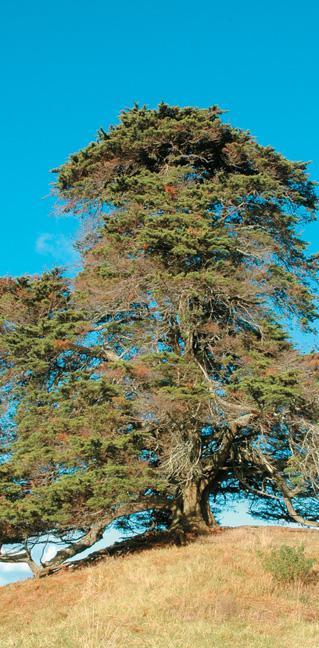

They also planted timber trees on the farm, including radiata pine, Lawsonia, poplars (sought-after for truck decking) and a 100-tree macrocarpa hedge.

When they retired, John and Ata shifted to Te Puna, Tauranga, but before leaving they brought in a

portable sawmill to cut down the exotic trees. Enough timber came out of the 50-year-old macrocarpas to build John and Ata’s son a new house on the farm, to pay the contractor and to keep John busy for a few years with future woodworking projects.

He made his rural-looking Te Puna fence from the trunks and branches of trees from the farm, using Lawsonia for the posts and Casuarina for the rails, treating the wood with Metallex. Later when several rails needed replacing, he used wattle and cherry.

John now has time to indulge in hobbies and interests that he was unable to do while farming. Besides his woodwork, he is helping to form a bird sanctuary in part of the Te Puna Quarry Park where introduced predators caused depredation of the native bird population. Part of his contribution to this project is to grow native tree seedlings to increase the native birds’ food supplies.

Macrocarpa timber, used here to make these breakfast bar stools, has been a popular species for shelterbelts and windbreaks in farming. It is only recently that these trees have begun to come into their own as a furniture and joinery timber, particularly with the control of native forestry species such as rimu and kauri. Macrocarpa is one of three cypress species commonly used in New Zealand. Cupressus Macrocarpa (Macrocarpa), cupressus lusittanica (Mexican Cypress or Lusitanica) and chamaecyparis Lawsonia Lawson Cypress. Macrocarpa and Lusitanica are often interchanged as “macrocarpa”. All the cypress species are a

similar in appearance, density, durability and all have a characteristic spicy, cedar smell when freshly cut.

Macrocarpa has been used as a substitute for kauri though its grain structure is less fine than that of kauri. Its use in windbreaks has given the timber the unfortunate reputation of being rather twisted in its grain. But shelterbelt and plantation-grown timber can have clean straight grain, and this kind of timber is easily worked. Macrocarpa is a low-to-medium density softwood.

It varies in colour from pink to golden-brown and will age to a dark honey-colour over time, unless it is exposed untreated to the elements, when it quickly assumes a silvery grey colour.

It is a naturally durable timber and will last 10-15 years in the ground and twice that above ground, untreated. This has contributed to its popularity, especially in farming applications and latterly as outdoor furniture.

All the “cypress” timbers have been used extensively in boatbuilding, furniture and joinery. They all machine well and can be finished to a high standard. The characteristic smell is supposed to be a deterrent to insects, particularly moths. Drying is a problem with this species. It cannot be kiln-dried green due to the potential for internal checking and collapse. Macrocarpa must be air-dried to

about 30 percent moisture content before it can be finished in a kiln and then at strictly controlled temperature and humidity levels.

Macrocarpa and the other cypress species shrink very little when drying, unlike radiata for example, and they move less in use, making them a good furniture timber.

Macrocarpa is a moderately stiff timber with a modulus of rupture of 74 MPa at 12% moisture. Lawson Cypress, also known as

Port Orford cedar or Oregon cedar (from its North American origins), is somewhat lighter in colour than either of the other Cupressus

species and considerably harder with a modulus of rupture of 98 MPa at 12% moisture. Furthermore it can be kiln-dried from green without the fear of checking and

rupture that attends the other two varietals.