An English Tall Case clock suits an antique clock mechanism

By Doug Tucker

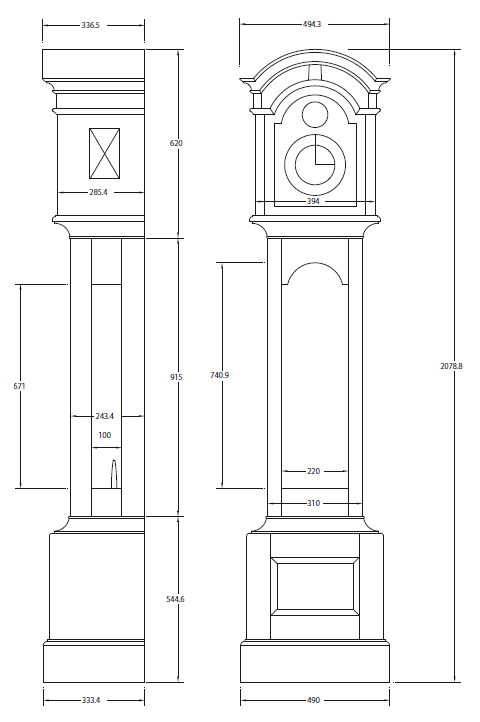

I had always wanted to build a grandfather clock case and was given the incentive when a client gave me a modern clock mechanism and a photocopy of a reproduction of an English Tall Case clock to follow.

I had to increase the plan dimensions to fit the mechanism, ash wood was chosen and I ended up with 23 metres of approximately 200 x 25mm rough-sawn at an average length of 2.4 metres costing just under $300. This is not the ideal style of clock case for anything other than an antique clock mechanism. In modern clock mechanisms, the pendulum swing (which should always be tested) needs a straight-waisted trunk style of clock. However, this project has been done to the requirements.

I designed this case with simple and easy access for future repairs. I see so many clocks where it’s a struggle to extract the mechanism because no thought has been given to servicing. Would I do it again? Absolutely, I enjoyed every moment of the 101.5 hours of construction time. The construction time was directly related to the quality of the build and I am very pleased with the result.

Timber

I bought two pieces of 300 mm wide timber, knowing I would have to cut off approximately 100mm to get them through my thicknesser. The timber was machined to 20mm thickness and then coarse-sanded to 18.3 mm.

My design was for 18mm, as this is readily available in pine at local timber yards. All lengths for the base and trunk of the clock were cut over length by 20mm. I tried to keep similar grains in pairs on either side of the centre, like a mirror image, and to balance the effect on the clock. As glass panels were specified, the only wide timber needed was for the base panels. For this, I laminated two pieces back together to give the large front panel.

I also decided to use solid timber for the sounding board carrying the chime rods and mount. There was no need for this to be a perfect match as it was inside the case. Fortunately, my sander would sand 400mm in width in one pass. I had designed the case to be in three pieces so that it was easy to transport.

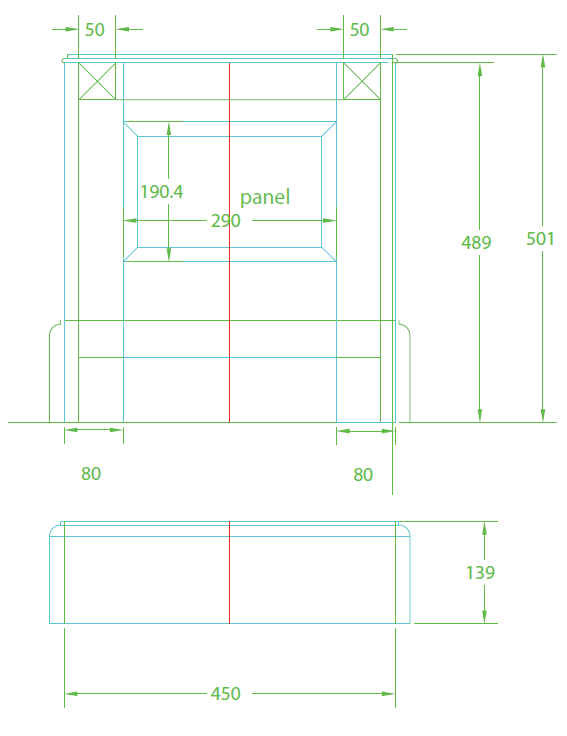

The base

I started on the base as the control for the rest of the case. The components were cut to size and finely sanded with 240 grit sandpaper. I began routering and rebating the various parts, taking care not to damage the fine finish. I was fortunate to be able to buy a vertical panel router bit in the shape I wanted in New Zealand.

I opted to groove the styles for the raised panels so I could glue in a tongue to give a tongue and groove joint. This gave me the panel groove in one operation. It also meant I could run the groove full length without worrying if had I stopped off at the right place. I routered the vertical front edges which were to be mitred with a 45-degree “F” cutter so that alignment was perfect and locked in place with only up-and-down movement. I used a 3mm round-over cutter for the styles and rails as, without overpowering the panel trim, I wanted to take off the sharp edge. I stopped this 20mm from the connecting part (internal corners).

Panels

I glued the front mitre joints first. Next, I used a 5mm round-over router bit so I could router the edge down to 20mm above the skirting board, then cut the panels on the router, taking several small cuts until I reached full depth.

This also helps eliminate chip or burn from the cutter. The machined relief of the panel edges is sanded before assembly as it is difficult to do when assembled. The glued-up and assembled base I left overnight to fully cure.

The skirting was cut with mitres for the front and sides. I routered an ogee profile on the top edge to add some decoration and to remove the square edge prior to cutting the mitres and lengths to size. I machined a mahogany strip 6mm thick, with a rounded front edge (bull nose), to fit around the top of the base unit, allowing a 3mm overhang and then a 6mm thick strip of the ash, to be set back from the mahogany strip by 9mm with a square edge. This breaks up all the white ash in the base unit and will be mirror-imaged at the top of the trunk just under the hood.

Finally, I cut and fit a ply back to stiffen the base. It is stopped short of the bottom edge.

The trunk

The client requested glass on three sides of the trunk so the door would overlap the side styles. To keep some symmetry, I have carried the glass heights from the front door through the side panels.

Glass is a departure from the traditional English tall case clock, but one that shows off the brass weights and pendulum bob fitted to this clock. A close-fitting ply back gives the trunk as much rigidity as possible and the inside is painted satin black so the ash ply does not detract from the brassware.

I set out the router work to be done in the order, so I didn’t get caught trying to run the ball bearing guide in a groove. I do the round-over edge around the glass first as this cannot be done after very easily unless you don’t mind running the bearing guide on the finished surface. This can mark that surface and make more work. I stopped the round over 20mm from the internal corners to match that done on the base around the panels.

I made a jig for this of a cross-section of the cross bar, with an extra piece added to stop 20mm from the final internal corner.

Rebate

For the rebate for the glass and grooves for the tongue and groove joints, I used an independent tongue joint again.

In placing the groove, I decided the glass would look nicer at approximately 6mm from the front edge, leaving a generous amount for the glass beading on the inside. I make the grooves half a millimetre deeper than the timber I’m working with, so with 18mm thickness, the half groove will be 9.25mm deep. This allows room for the glue and any variation in the machine depth.

The length of the glass is then marked for the groove to be turned into a rebate, but only where it is required. Hand-finished corners make a neat job. The rebate down the back of the trunk for the ply back is simple and straightforward, half the timber thickness and the depth of the ply thickness. Now make the fillets to be used as tongues in the jointing of the sides (a nice slip fit is desirable). These do not require finishing as they will never be seen again. I use a reasonably fine sawn surface which allows room for glue. Fine finish the sanding work on the surfaces that you will not be able to work easily when it is assembled.

Take care when gluing not to damage finished surfaces with glue or clamps. Cover with clean paper and a clean scrap of timber with no chips to dent the finished surfaces.

Cross timbers

With the sides glued up, the cross timber can be mounted. As the trunk of the clock is the most fragile item I have screwed the cross timbers where they will be covered with mouldings, making the trunk stronger in the joints.

Next, the backboard is cut and fitted; this is for the chime rods to be mounted on and is used as a sounding board. Here I used screws and glue to fix it in place after making sure that it aligned correctly and was plumb. The trunk is screwed in plumb to the base and left to fully cure overnight. This needs to be watched, as out of plumb, the weights can catch on the internals of the case on the way down.

Back ply

I left cutting and installing the base ply until I had marked up the nicest piece for the trunk. The base ply overlaps the bottom rear rail of the trunk so there is no light penetration through the joint and helps in positioning the trunk to the base. The ply cut for the trunk had to be painted black. The trunk was fitted to the base and the trunk ply was tacked in place.

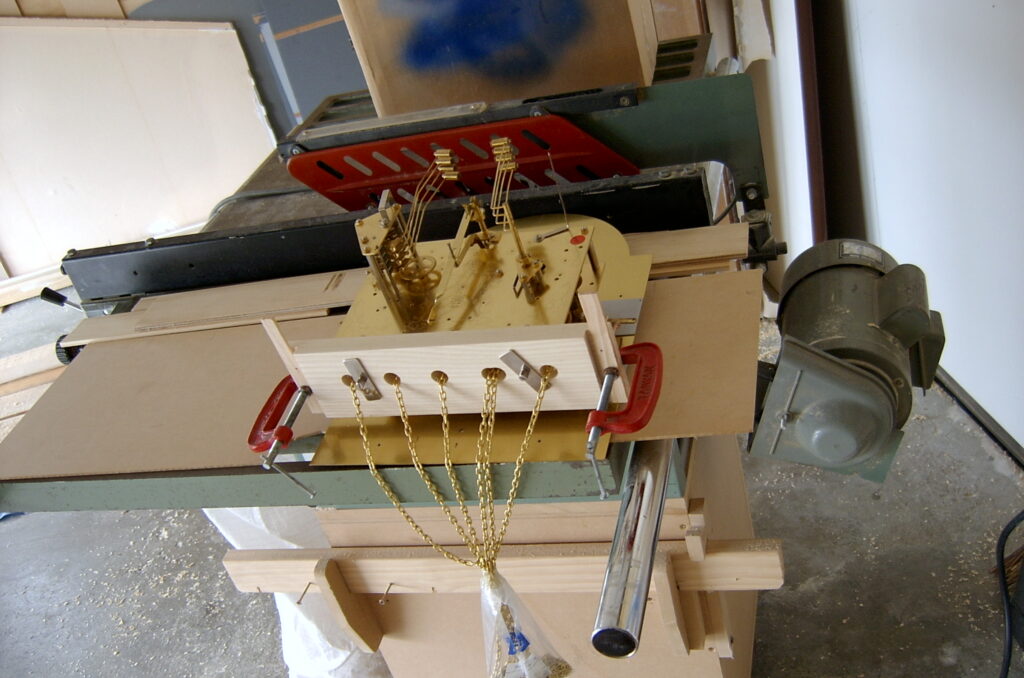

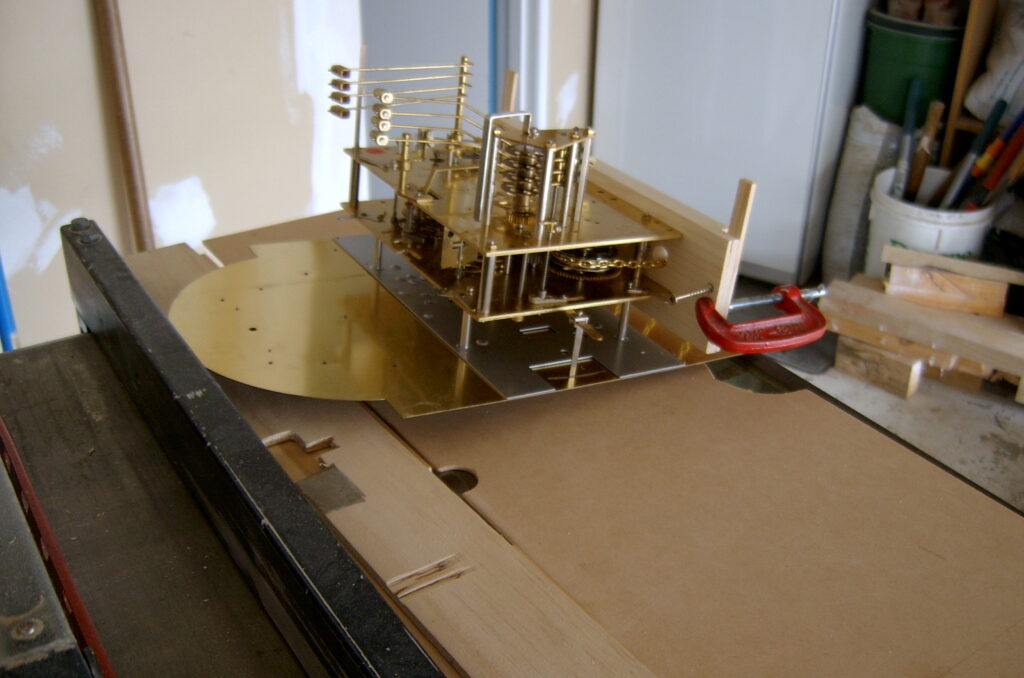

With the hood runners clamped in place on the trunk sides, the seat board that the clock mechanism sits on was made to fit between the runners. I drilled out a hole for each of the six chains, making sure that the chain end fittings would go through the holes, saving them from being stressed in removal and re-attachment. I drilled two 5mm holes for the mounting screws, so there was a little movement if needed.

Mechanism

Now the clock mechanism can be mounted and the fingers crossed that all is as it was designed to be. Note that for this style of clock with a narrow waist, a smaller pendulum bob is required. I have used a 5 ½” (140mm) bob which swings no further than the weights hang. A 6 ½” bob (165mm) does not look right and will hit the glass side panels.

Check that the weights will pass all the timber on the way down and that the pendulum does not strike the sides of the case. With the dial mounted to the mechanism, I checked that it sat where it was planed to sit and then checked that the chime mounting block mounts, to the backboard and the rods, hung in the correct place for the hammers.

To finish off, screw the seat board down in place. I have left the clock ticking for the time being and will have to lubricate it, as it is dry and damaged from years of being shunted around in inadequate packaging.

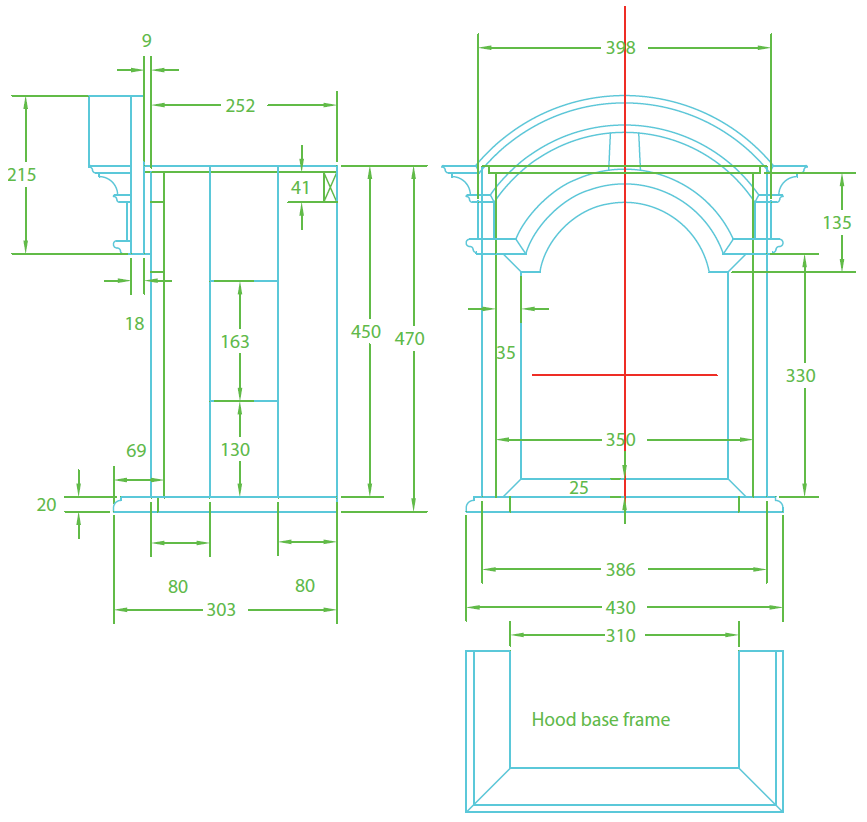

The hood

With the main parts of the hood cut to size and fine-sanded ready for the routering and final length cuts, I work on the hood base which is also the rails that secure it to the clock hood when installed. This has an ogee shape routered around the top edge and is mitred on the front corners. I leave the sides oversize to be trimmed back when the correct position is confirmed.

The front mitres are my usual tongue and groove method but with a hidden joint, not machining, all the way through to the front of the mitre. This part is going to see a lot of handling and the extra strength will be a bonus. The sides will have the same construction as the trunk sides and base panels. The small round-over radius is routed in the internal edges of the styles and rails, which again is stopped short at 20mm from the corners.

The back of the groove is removed between the top and bottom rails and on the top and bottom rails themselves so that it becomes a rebate for the glass. When machining the front pair of styles for the sides, I also grooved the internal side to joint a fillet strip to close the gap between the side panels and the dial outer edges. I use glue joints wherever possible with just eight screws and a handful of nails for the ply backs and to secure the hood rails to the hood side panels. You could screw the rails on.

Upper coving

Between the fillets, I machined the upper coving for the dial. This coving is the shape of the top edge of the dial and overlaps it as the fillets do by 5mm, hiding the rivets attaching the edge of the dial to its backing plate. This is grooved to match the groove for the fillets.

The sides, dial fillets, and the top can all be assembled and dry-checked for fit, then glued and clamped until dry. For the front panel above the dial and door, I continued the break arch dial shape through the panel with an increasing diameter to give the look of ever-increasing circles.

The bottom edge of the front panel has an ogee shape routered into the lower edge and around the corners where another moulding of the same shape will continue the shape around the clock sides. The two side mouldings have a round over upper edge as they are only a small bar and not as tall as the front panel, which will carry the final topmost moulding. They carry the moulding line along the sides to balance the moulding band around the clock.

Hood moulding

Use the ever-increasing circle size through to the top moulding and allow for it to be wider than the one below. The higher up the hood gets, the wider it gets, to match the bottom of the hood rail width. This moulding is 30mm high and has the grain horizontal whereas the front panel it is glued to is a vertical grained panel.

This contrast is accentuated with mahogany strips in the middle and at each side vertically. For this highlight panel, a contrasting timber like burl walnut could be used to good effect. The moulding is again fitted to both sides, taking the moulding line around the hood. When the sides are together and the hood rails on, cut and fit a ply roof panel while the hood is temporarily held in the correct place and square. The mouldings can then be fitted and glued into place.

Until the support rails are made, (coved mouldings) the hood is held up with blocks of wood tacked in place. I removed the hood to lessen the danger of the blocks falling off under the hood’s weight.

Trunk mouldings

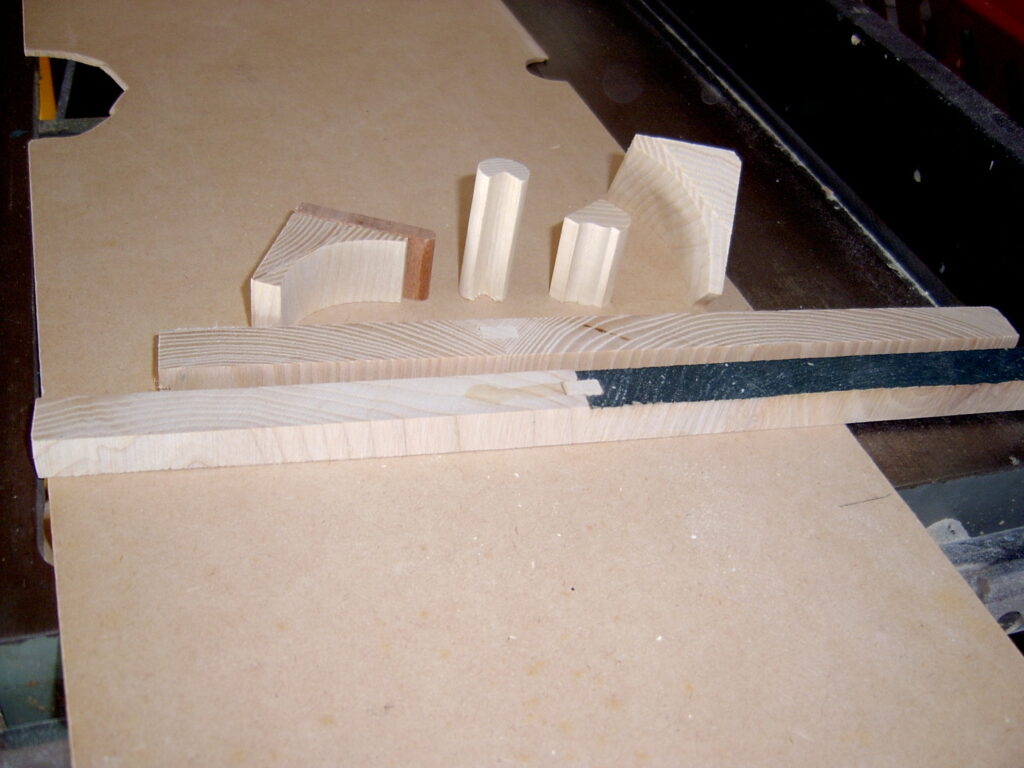

The major mouldings at the top and bottom of the trunk are last, cut from 40mm by 70mm laminated timber to leave them looking like only one piece. I marked the shape on the end of one of the strips as a guide, then roughed it out on the table saw, leaving around 3mm on the surface to finish. As the shape will run across two sides, I left a 2mm fin on the edge that is the transition of the two sides. This supports the timber flat.

I clamped a piece of similar-sized scrap alongside this fin to hold the timber flat as the fin was removed, making the curved shape, just like a coving moulding.

I set up a straight edge diagonally across the table saw to give me the correct height and length cut. Here, I prefer the trial and error method. Varying the angle across the saw bench changes the width of the coving. This is not the first time I have used this method to make a strip of coving, but extreme caution must be used. I do this with the riving knife and guard removed so it is imperative that utmost care be taken in this operation. When doing the cutting, feed through slowly and steadily, as any hesitation will leave a lot of sanding to be done. I hand-sanded these mouldings with sandpaper around a small tube on it. The result was worth it.

Murphy says hello

I did not make more than I required and this is a bit short-sighted as one mistake means “start again” is the order. Murphy’s law raised his ugly head and I cut one mitre on the wrong face. I salvaged the offcut and glued it back on with the specified dark stain. I hoped I would get away with it!

Once it was dry, I re-cut the moulding and fitted them into place so I could mark the ends of the sides to square-cut off. I ended up with barely 3mm of the mistake showing on one of the rear corners. It will hide very easily, a big relief. After the mouldings were glued into place and clamped as best as possible, I tried the hood on to keep Murphy at bay, then set it aside while the glue dried before the weight of the hood rested on the upper mouldings.

Doors

With the case complete, all that remains is to assemble the doors for the hood and the trunk, cut enough beading for all the glass and the two pillars and I’m ready to mount the doors and hardware. I cut double the quantity of beading required with there being a very good chance that some will split when tacked.

The doors are made like the other panel joints and as there is glass and not an infill panel there is no difference technically. I took care in assembling the hood door as the parts aren’t strong. The bottom rail has a very small cross-section and I decide to not router out the rebate for the glass but to leave it as a U-shaped groove to more strength to the joint.

The glass can be dropped down into the groove and then pushed in flat at the top and beading up the sides. It may even have to be RTV glued in to give additional strength to the hood door frame. The interesting part to rebate was the break arch top rail. Fortunately, the rebate ran completely through. I have a grooving router bit with a roller guide and this was used to remove the back side of the groove to produce the rebate.

The same procedure is used to cut the rebates in the trunk door which are now assembled and left to completely dry overnight. I now added a strip across the top of the trunk door to hide the end grain and joints on the door top. When the door is opened you look straight at the top of the door.

Hinges

With the doors now ready, the rebate for each hinge can be routered. I was able to use a template for the brass hinges I had.

The depth of cut is the thickness of a closed hinge; this has been done to facilitate fitting the doors to the styles, which eliminates the accuracy needed to align the door hinge rebates as a mirrored pair. I have used three hinges on the trunk and two hinges on the hood.

Finally, the pillars will be made as a three-quarter round and fitted to the outside edge of the hood front styles. This allows clearance for the hood door to be opened wider. As a clockmaker and repairer, I find hood doors that open only 90 degrees are restrictive. When there are children around, it is safe practice to fit a lock to the trunk door to prevent them from playing with the chains and pendulum. For me, it is not the best idea, as I make my living fixing these problems but I know there are no small hands in residence with this client.

Staining

Before staining, check that all the timber is fine-sanded then vacuum or air-blow off all the dust.

I would have suggested an alternative timber for the dark finish, but the plan began with a light finish. Tinting a clear coat does not give the same finish as staining so use some stain mixed in the top coat. The two finishes are quite different but the same product is used.

I have rubbed in a black bean stain to fill and highlight the grain, then I mixed stain with clear coat, cut the mix to use it as a sealer coat and sprayed the entire case. This gives colour between the grain which, being hardwood, has not taken a colour from the stain. Don’t forget to stain the glass beading when you are doing the clock case. Then it is two coats of clear Danish Oil to finish. All that remains is for the glass to be fitted and the clock to be delivered and installed. When installing this style of clock it is important that the clock is vertical, as any variation will cause the pendulum to swing further on one side of centre than the other. This can result in hitting the glass sides.