World’s rarest motorbikes re-created here in

New Zealand

By Roger Lacey

Photographs: Roger Lacey, Doug Cornes

The legendary Manx Norton was the first single-cylinder motorcycle to lap the famous Isle of Man TT circuit at an average speed of 100 miles per hour (160 km/hr). Made from 1946 until 1962, the bikes became a favourite of privateer racers and in more modern times, a popular choice for classic motorcycle racing.

Today, half a world away from the original Birmingham factory, a small Kiwi company is restoring and supplying parts to Manx Norton owners around the globe. The company’s reputation for excellence is down to the owner, Ken McIntosh whose wealth of experience and dedication to detail has seen him entrusted with some of the rarest motorcycles in existence.

The outside of his factory looks like every other one in the block, to deter unwelcome attention there are no signs outside. However, entering Ken’s workshop is like stepping into an Aladdin’s cave of glittering silver.

Motorbikes are everywhere. Two rows of racing machines are lined up down the middle with the current projects up on stands. The mezzanine floor displays a row of bikes as if hung from the wall.

Doors lead off to a clean room for engine preparation and a polishing room with bead blaster, linisher and grinders. A lathe, vertical mill, drill and capstan lathe are along one wall with fly press and rack press on benches in front of them.

Top marks

Ken invites me into the office and explains how it all started when he and his older brother got into motorbikes as schoolboys. His brother first bought a 1948 BSA C10 then a collection of ex-army Indians; Ken found a Royal Enfield 250 for free. While repairing the Enfield, he met New Zealand motorcycle champion Len Perry who ran a motorcycle shop in the suburb of Greenlane in Auckland. Len’s support and advice encouraged him into an apprenticeship as a motorcycle mechanic. He started at Bill Russell then moved to Whites and then Auckland Motorcycles Ltd, gaining top marks in New Zealand for all his exams.

With ambitions to race motorbikes, he went against the traditional route of starting on small, low-powered bikes. He decided he wanted to ride nothing less than the best—a 1000 cc Egli-framed Vincent. Saving his apprentice wages, he visited the post office every week to buy two-pound postal orders until he had enough overseas funds—government regulations then required imports to be paid for in part by funds held out of New Zealand—and sent off to buy a special racing frame designed by Swiss engineer Fritz Egli.

Precision

He had already bought a second-hand Vincent 1000 cc engine, but found it was a virtual basket case. Undaunted, he sought out a local toolmaker, Dave Whitehead who took him under his wing and taught him the precision engineering skills he needed to repair it, including making a new crankshafts and cams.

All this took time and when finally the bike was ready for the track, the new generation of Japanese bikes had begun to dominate racing in New Zealand. Ken McIntosh’s first race was the Group B curtain-raiser for the 1975/76 Marlboro International series. All bar one of the other bikes on the grid were Japanese two-strokes.

Ken got a good start and was somewhat surprised to find himself in second place. The leading bike was slightly faster and the rider was taking it easy, confident of the win when Ken, on the last lap, out-braked him into the hairpin and held on for an unexpected victory.

“My professional racing career has been all downhill from there,” Ken says with a wry smile.

While the Egli Vincent was fast, it struggled against the lightness of the modern Japanese machines. Reluctant to join the two-stroke crowd, Ken started building a copy of an Egli frame for the new Kawasaki 900 engine. Before it was finished, he decided it was not Egli’s finest design and thought he could do a better job himself. The Kawasaki frame design was then modified to suit the more powerful Suzuki 1000 engine.

Rodger Freeth

In the meantime, motorcycle racer Rodger Freeth, found his new 500 cc GP bike would not arrive in time for the beginning of the new season. As a stop-gap measure, Rodger persuaded Alan Skousgaard (whom he had never met) to lend him his recently ordered McIntosh chassis. He borrowed Keith Turner’s Yoshimura Suzuki GS1000 race engine.

The engine was pulled out of the standard Suzuki chassis and fitted to the first McIntosh-Suzuki frame. Rodger, on the McIntosh Suzuki, entered 12 races that season, winning ten—every race that he finished—shattering the dominance of the Yamaha TZ 750 two-strokes.

Ken, by that time has started his own business building road-legal McIntosh Suzuki’s during the day and working night shifts to help pay the bills. The motorbike frames were identical to the racing machine with just the addition of light brackets.

Roger took his second McIntosh Suzuki to the Arai 500 at Bathurst and won in 1982, came second in 1983, took 1984 off to complete his PhD in astro-physics and returned in 1985 to win again with his fourth McIntosh-Suzuki. The successes in Australia and locally lead to Ken selling more than 40 McIntosh Suzukis.

Classic

In the meantime, classic motorcycle racing was gaining popularity. Ken McIntosh’s Egli Vincent, now with a McIntosh-built frame, was being ridden successfully by Hugh Anderson who had been four times a world motorcycle champion and 19 times a New Zealand motorcycle champion. Having such a high-profile rider campaigning on his bike led to a stack of enquiries about Ken’s work and his machines.

Gaining work from the classic racing scene meant that business moved away from the modern machinery towards tuning, repairing and supplying parts to old racing machines, especially Manx Nortons.

Ken McIntosh can now supply all the parts to build one from scratch, right down to the last nut, bolt and washer. Everything is as close to authentic as possible with the odd, hidden modification to improve reliability.

Many parts of the parts he sells are made in-house, including copies of the original Featherbed frames. I ask him if he can tell the difference between his and an original one. “Usually,” he replies with a wink, “our welds are a bit neater.”

Clutch and brake levers are faithful reproductions right down to the hollow spherical balls on the ends. A capstan lathe in the corner is used to make otherwise unobtainable cycle thread nuts and bolts.

Rare

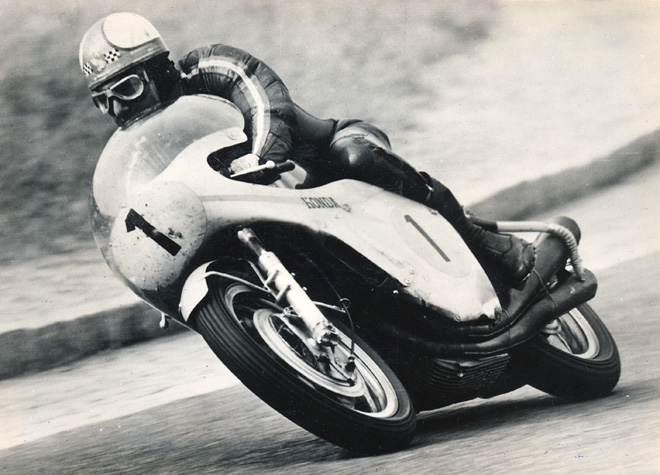

Ken employs two staff and is kept busy with enquiries from New Zealand and around the world. He has been entrusted to work on some of the rarest and most valuable machines in existence. This includes the 1967 Honda RC-181 500 four raced by Mike Hailwood at the Isle of Man TT.

Only three 500 cc bikes were made and the other two are in the Honda museum. The bike was entered in the 2008 Legend of the Motorcycle International Concours d’Elegance held at the Carlton Ritz, California and won first prize in the 1950 to 1977 class.

Ken has a passion for his work and with his skills and attention to detail has managed to make a business from it. But it hasn’t been easy. And he has advice for anyone thinking of buying an old motorbike to do up for a profit: “If you are given the road bike for free and the toolbox has $5000 in it, then you might just break even if you come to sell it.”

He acknowledges for most people the rebuild is a (mostly) enjoyable hobby and asks, “How much more would you pay for a jig-saw puzzle that was already assembled?”

Although Ken sells parts to restorers of road bikes, he usually works only on racing machines.

In a strange twist, Ken’s McIntosh Suzukis have now become sought after by collectors and he has been asked to maintain and restore some of the bikes he made almost 30 years ago. Whatever the future holds, whether working on classic bikes or his own bikes, he will not be short of work.

Winning

The Manx Norton classic bikes that Ken McIntosh is associated with are constant winners. During the first Barry Sheene Trans Tasman Challenge at Labour Weekend this year, champion Australian racer Cameron Donald, a former Isle of Man TT winner, took out the Senior 500 cc New Zealand TT for Pre-63 motorbikes at Hampton Downs riding a McIntosh Manx Norton. Second was Nick Cole on a Norton Special which had a McIntosh frame that was built more than a decade ago.

At the same meeting, the New Zealand Classic Junior TT was won for the third time by Neville Bull riding Robert Creemers’ 350cc McIntosh Manx.

In September 2010, the New Zealand Superbike champion Andrew Stroud rode this largely original , Auckland-built 500 cc McIntosh Manx Norton to win the Australian Historic Championship at Phillip Island. At the same meeting in wet conditions, Stroud (42), scored a brace of victories in the 350cc class with another Manx Norton prepared by Ken McIntosh and owned by Kevin Grant.

Ken McIntosh had not tackled an Australian championship since Rodger Freeth rode the legendary McIntosh Suzukis at Bathurst.

In 2009 at the Pukekohe Classic Festival, Kevin Schwantz rode the same 500 cc McIntosh Manx Norton for a lap record and a winning slate.

On another winning note, at the 2008 Legend of the Motorcycle Concours d’Elegance, the first place for 1950-1977 competition bikes went to Mike Hailwood’s 1967 Honda RC181-500, owned by Virgil Elings of the Solvang Motorcycle Museum and worked on by Ken McIntosh of Auckland.

By the numbers

As reported by the New Zealand Classic Motorcycle Racing Register, the winning Manx Norton (see “Winning”) has a full set of original Manx components including a standard spec Manx frame and forks, brakes, chain primary drive and period AMC clutch, plus an original Lucas 2MTT magneto, Amal GP carburettor, and Smith ATRC tachometer. The period-type modifications are the old-style Quaife six-speed gearbox and the UK-built Summerfield 92 mm bore motor. The external appearance of the motor is completely standard except for the enclosed coil valve springs which kept the motor completely oil tight. Inside the motor, the modifications are a plain bearing crankshaft (as used in 1961 by Mike Hailwood to win the Isle of Man TT race) and the bore and stroke changed from 86 mm x 85.6 mm to 92 mm x 75 mm, using a Nikasil-coated cylinder. Norton themselves changed the bore and stroke of their own race engines many times between 1937 and 1959 and won the 1954 Isle of Man TT with a 90 mm bore.