A former motorcycle racing star is still championing his favourite bikes

By Jon Addison

Photographs: Geoff Osborne

He might describe himself as a larrikin biker, but former world motorcycle racing champion Graeme “Croz” Crosby is really more of a modern Renaissance man.

Put simply, a Renaissance man is defined as a very clever person who is good at many different things. So check the Croz record thus far: Champion motorcycle racer, commercial pilot, successful author, businessman, house builder, skilled motorcycle mechanic, enthusiastic cook, raconteur – the list goes on. He can speak a little Japanese, bake a soufflé or lace up a wire-spoked bike wheel. And even though he turns 62 this year there’s still quite a bit of the larrikin left.

It almost goes without saying that Graeme has a shed. Well, it started out as a hobby shed, somewhere to tinker with old bikes and other motorised toys. In typical Crosby fashion, though, it has become the headquarters for a thriving business restoring and exporting classic Japanese motorcycles. Graeme and his wife Helen bought a 12 acre (4.8 ha) block in the picturesque Matakana countryside an hour north of Auckland more than eight years ago, built a spectacular house, the shed and, across the road, Helen’s The Vivian art gallery.

The 230 square meter shed now houses Graeme’s office, from where he sources parts from around the world, tracks down donor bikes and deals with an increasing customer base; a massive store of new and used motorcycle parts; an oddball collection of donor bikes and two men working full-time rebuilding classics, mostly Kawasaki Z1 machines from the mid-1970s, building replica Moriwaki Kawasaki racing superbikes and fabricating the odd part that’s unobtainable or a one-off for a customisation project. And in one corner there’s a commercial kitchen, although it’s mostly filled with bike parts.

Graeme’s customers are, like him, baby boomers. He explains: “The old British racing bikes are getting too hard to keep running and their owners are getting old. The baby boomers grew up with the early Japanese stuff and now they have a bit of money and want to re-live their youth.”

He and his customers enjoy riding 40-year-old road bikes but are also into classic bike racing, where bikes are “silhouettes” that look like the factory models of their era but with some modifications to enhance performance and reliability. Components such as engine cases and cylinder heads have to be original and carburettor sizes can’t be changed.

“They are more human,” Graeme says. “Modern MotoGP racing has disenfranchised me as a former racer. You aren’t allowed into the pits so you only see the racing from a distance.

“With the classic bikes you’re encouraged to come into the pits to see the gear close up and talk to the riders and mechanics,” he adds.

“The baby boomers grew up with the early Japanese stuff and now they have a bit of money and want to re-live their youth.”

Exciting machines

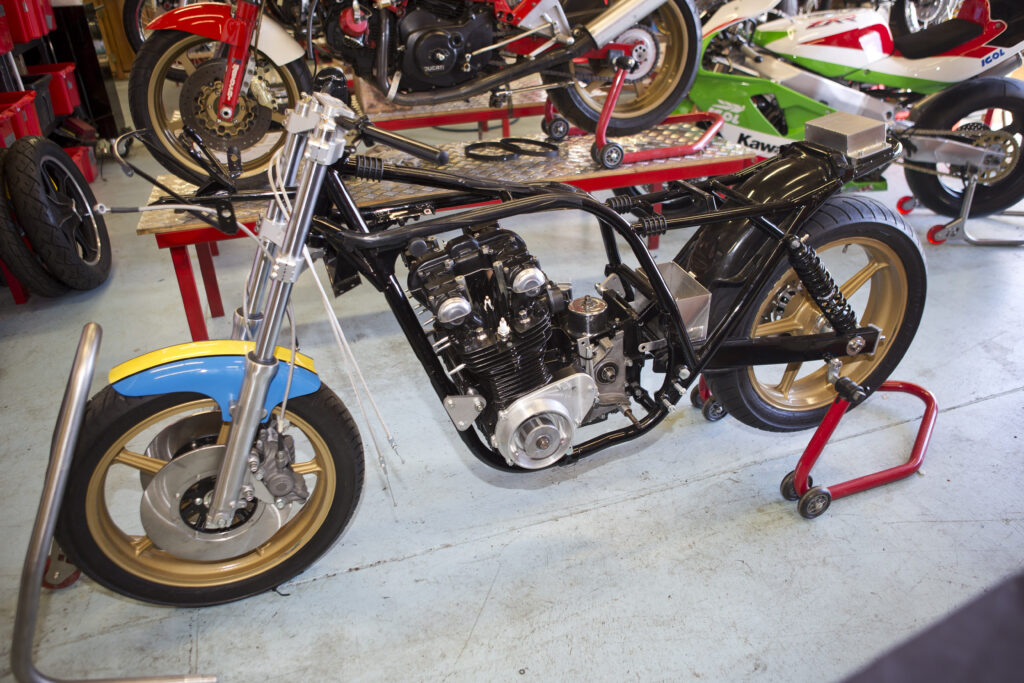

Although the Crosby team will build almost anything to meet a racing customer’s requirements, easily the most exciting machines are replicas of the Moriwaki Z1000 Kawasaki superbikes, which more than any other bike created the Croz reputation. Graeme raced for Mamoru Moriwaki in Japan and Europe in the late 1970s and on the sit-up, wide handlebar superbike beat full-out racing machines in spectacular style, pulling wheelies and smoking the rear tyre, much to the delight of huge crowds.

The team in the Matakana shed is building a limited edition of 10 of the Moriwaki replicas, although oddly one has “11 of 10” on a small plaque on the top triple clamp. “A customer in Britain would only buy one of the bikes if we numbered it 11,” Graeme laughs. “So we did.”

During his racing career Graeme developed a close relationship with the two great Japanese performance tuning houses, Moriwaki and Yoshimura, which explains his grasp of the difficult Japanese language. He still sources parts from them and visits Japan at least once a year. The two engineering companies are related, with company founder Mamoru Moriwaki marrying Namiko Yoshimura, the daughter of superbike pioneer Hideo “Pops” Yoshimura.

Graeme’s visit this year will coincide with the 40th anniversary of the first Suzuka eight-hour race, which he rates as “probably the highlight of my career, with a crowd of 160,000 people watching”. His co-rider, American Wes Cooley, was a diabetic and in the intense heat was able to complete just the minimum number of laps leaving Croz to ride most of the race.

“It’s a great circuit, highly technical and it turned out to be a great race,” he recalls. “After eight hours I won by just 12 seconds with [American] Eddie Lawson and [Aussie] Gregg Hansford right on my hammer.”

Building replicas

Much of the building of the Moriwaki replicas and Kawasaki Z-series recreations is done by Tim Stewart, in his own way another motorcycle racing legend who has been part of the Crosby team for the past five years. Tim worked on both the Britten and Buckley motorcycles so is probably the only person to have been intimately involved in the creation from scratch of two different racing motorcycle engines. He also crewed on the bikes and crewed for American racing legend Kenny Roberts in Europe.

The Crosby shed houses pretty much everything that would be required to build a new motorcycle – a lathe, milling machine, welding and painting equipment – but the cost of a completely hand-made machine would be prohibitive. A fair bit of machining work is out-sourced to local companies, including Warkworth-based Core Builders Composites Ltd, owned by the Oracle America’s Cup team, where manager Tim Smyth takes a close interest in the bikes.

Many parts used on the Kawasaki road bikes are new because it’s simply not worth trying to repair the originals. “For example, I bring in brand new fuel tanks from Japan, painted in the factory colours, because the originals will invariably have deteriorated badly on the inside,” Graeme says. “Same thing with the wiring looms – the originals will all have been mucked around with at some stage so we put in complete new ones.”

He’s amused by the “anoraks” who believe every original part should be restored or replaced by a new factory component. “Doing that would add $15,000-20,000 to the price of the bike. You have to be practical and pragmatic about it.”

Performance boost

Besides, it wouldn’t really be a Crosby recreation if everything was left bog-standard. In fact the Crosby Kawasakis are better than the originals in one important respect – they perform better.

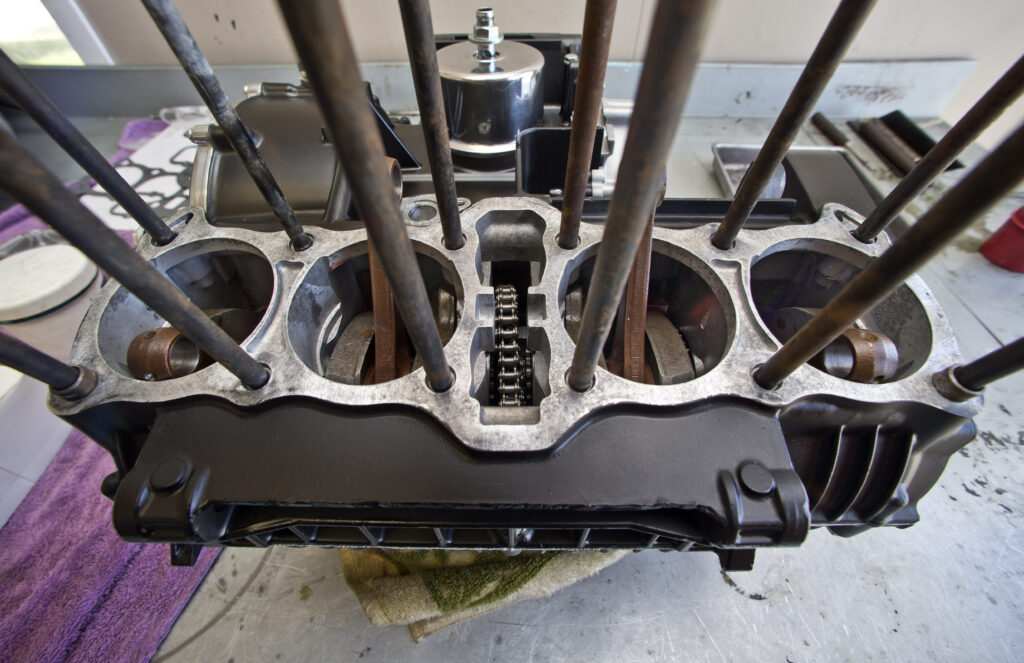

“The original Z1 had about 82hp, but we’ve upped that to around 130hp,” he explains. “We bring in better pistons from the US, raise the compression a bit, fit racing valve gear, do a bit of porting and polishing, put on new carbs and electronic ignition and improve the exhaust systems. We also fit AP brake calipers to make them stop a little better.”

Although the Crosby team – the third member is Gary Lawford – concentrates on the Kawasaki Z1, or Z900, along with the closely related Z1B and Z1000, it also recreates the mid-1970s Kawasaki two-stroke 500cc and 750cc bikes. Other brands aren’t always shown the door either, with iconic Suzuki 750cc “water bus” and Honda CBX six-cylinder bikes being worked on when The Shed visited.

Each recreation leaving the Crosby shed is fitted with a small plaque featuring a tiki, which has inspired him for 35 years. “I was on a DC10 heading back to England in 1979 and thinking about what I could put on my helmet as everyone from New Zealand had a kiwi of some sort on theirs,” Graeme explains. “On the plane they were giving out little green plastic tikis and that decided me, but ironically I ended up with a kiwi as well because I took out a contract with the Swiss helmet company that made Kiwi helmets. The Swiss had contracted a company to come up with a single word that meant the same thing in every language and kiwi was the result.”

After finishing runner-up in the 1982 500cc World Championship (equivalent to today’s MotoGP) on a Yamaha, Croz hung up his racing leathers and returned to New Zealand where he owned a motorcycle dealership, sold new Mercedes-Benz cars, flew commercial aircraft for Northern Air and even did a stint building houses in Fiji.

“It’s a great circuit, highly technical and it turned out to be a great race,” he recalls. “After eight hours I won by just 12 seconds.”

Biography

Along the way he was asked by HarperCollins to write a book on his career. A professional ghost writer prepared a few paragraphs and so did Graeme. The publisher preferred Graeme’s writing and in typical Crosby fashion his keyboard had a better throttle than brakes and he produced almost 50,000 words more than required, so had to learn about editing. The result, Croz: Larrikin Biker, went on to become one of the most successful books about a New Zealand sportsman.

The Crosby culinary experiences include serving horse meat barbecues to fellow riders in Europe, but these days he belongs to an informal association of local men from all walks of life who enjoy cooking. Each month one of them arranges for a chef to teach them how to prepare different foods.

Outside the shed or the kitchen Graeme manages a bit of road riding on either a 2007 Isle of Man anniversary Suzuki GSXR1000 or a Harley-Davidson Road King.

He still rides competition bikes, but only in demonstrations. This year he will star at Eastern Creek in Australia, the Goodwood Festival in England and at the Sachsenring in Germany. “I still like to go quite fast, but not as much as I used to because I know my limits now.”

Header Winning ways

Although Graeme Crosby won the hearts of motorcycle racing fans around the world with his spectacular wheel-standing and wheel-spinning riding style, he was also remarkably successful during a career spanning just nine seasons.

A brace of world TTF1 (Tourist Trophy Formula 1 – precursor to the Superbike World Championship) titles and runner up in the 1982 World 500cc Championship (forerunner of today’s MotoGP) ensure his place in the record books.

Highlights of his career include:

1974: Nine victories in New Zealand on a Kawasaki H2 and third place in the Castrol Six Hour race at Manfeild.

1975: Victory in the Castrol Six Hour on a Kawasaki Z1 900 and two open production class races.

1976: Another win in the Castrol Six Hour and two victories at Sydney’s Oran Park Raceway on the Ross Hannan Yoshimura Kawasaki Superbike.

1977: Another win in the Castrol Six Hour, on a Z1000, along with nine wins and three podiums in Australia on a production Kawasaki Z1B and the Hannan machine.

1978: Again winner of the Castrol race on a Kawasaki Z1R, with seven wins in Australia on the Hannan Yoshimura.

1979: Four wins and a dozen podiums on a Moriwaki Z1000 Kawasaki, with second place in the British TTF1 and third in the World TTF1 Championships.

1980: Some 13 victories and half a dozen podiums on various Suzukis, claiming victory in the World TTF1 Championship along with runner-up in the British TTF1 and 500cc championships.

1981: A total of 18 wins and 13 podiums on various Suzukis, including winning the World TTF1, British TTF1 and British 500cc titles, along with fifth place in the World 500cc Championship.

1982: Won the Daytona International 200 mile race on a Yamaha YZR750 and took six wins and five podiums on a Yamaha OW60 500cc grand prix bike, taking runner-up in the World 500cc Championship.

“His keyboard had a better throttle than brakes and he produced almost 50,000 words more than required.”

Header: King of the road

In the early 1970s the fastest production motorcycle in the world was Kawasaki’s big Z1, which quickly earned the title “King of the Road”.

Honda’s launch of the CB750 at the 1968 Tokyo Motorcycle Show signalled the creation of the superbike and the demise of the dominant British motorcycle industry.

Ironically Kawasaki, which that year launched the notorious three-cylinder, two-stroke 500cc H1, known as the widow-maker for its propensity for spitting its riders off into the scenery, had already begun the design of the four-cylinder, four-stroke 750. That project was put on hold as Kawasaki monitored the sales impact of the new motorcycle style and began conjuring up a machine to trump the Honda.

The result was the 1972 launch of the astonishing Z1 with a 903cc engine rated at 82hp at the time the most powerful bike engine ever produced in Japan, 22 per cent greater than the Honda.

What’s more it sported twin chain-driven camshafts to out-do the Honda’s single cam and proudly proclaimed the fact with double overhead camshafts badges. Its “square” 66 mm bore and stroke dimensions and four carburettors meant it pulled strongly, yet revved willingly.

The Z1 was clocked at 212 km/h, making it the world’s fastest production motorcycle from 1973 to 1975. That title had been held in an unbroken run from 1949 by British bikes such as Vincents, Nortons, BSAs and Triumphs. No British bike has held the title since.

Around 85,000 Z1 bikes were made and sold around the world until 1975 when it was superceded by the similar Kawasaki Z1B, which boasted a little more power but better handling through a stiffer frame and better suspension components. The Z1000 followed two years later.

Kawasaki Heavy Industries is a huge, diversified Japanese company that was founded as a shipyard in 1878. Along with interests in shipping, aircraft and railways it began building motorcycles after World War II. The company is still a major player in the New Zealand market with a range of street bikes, farm bikes and utility vehicles, moto-cross bikes and jet skis.