Bob’s Tips for the Metalworking Shed

By Bob Hulme

Photographs: Bob Hulme

Setting Up

You may already have your shed well set up to suit your needs, but if not here are some ideas to get you started. (or to improve your current arrangement).

Mount your vice so that the fixed jaw is extends beyond the front edge of the bench. This ensures that anything large that you put into the vice can extend down as far as the floor without fouling against the bench. Soft jaws are important for those times when you don’t want ugly teeth marks on the job you are holding in the vice. It’s no good blaming it on the dog. Those excuses ran out years ago when you blamed the family pooch for eating your homework! Nowadays there are ready made magnetic soft jaws that simply fit onto the existing vice jaws and they don’t cost the earth either. I have been fortunate enough to have had plenty of offcuts of aluminium lying around to make my own from, but I know that is often not the case in most home workshops.

If your workbench does not have drawers you can make great use of the space under the bench anyway by using inexpensive plastic bins. (See photo) I use these ones that I bought from one of the larger hardware retail chains for around $5 each. They stack on each other and I have labelled them with a marker clearly so I have no trouble finding what I want.

A set of good ring/open end spanners is a must and I find that a good way of keeping them together is with a spanner ring. (see photo) It also means that you can hang the whole set up on one hook. Having each spanner on its own hook on a shadow board is lovely, but takes up a lot of space and it is not so easy to grab the whole set and take it to the job you are tackling. Being a bit pedantic, I put the spanners on the ring in size order so it is easy to find the particular one I want. Saves time and if one is missing, it is easy to spot. Plastic holders and roll up bags are good too, but spanner rings are good for when those holders give up. (usually well before the spanners themselves are worn out)

A cheap way of creating cupboard space is to watch for auctions of used office furniture. I have found that credenza units work well when mounted up on a wall and they don’t cost that much. Amazing how few businesses will tolerate ageing office furniture. They only seem to want new, so the old stuff can be bought real cheap.

Files

Good sharp files are an asset, but blunt worn out ones are only good for grinding up into scrapers, etc. However an underperforming file might just need a clean to get it back to usefulness. Invest in a file card – a small wire brush like thing with hook shaped bristles specially shaped for cleaning the grooves in files.

Another way to clean a file is to use a piece of brass and rub across the file in line with the grooves. Some people say that old files can be given a bit more life by sand blasting them. I have not tried this myself, but if you have a sand blaster at home it would not hurt to try it on an otherwise dead file.

Another tip to help stop clogging of file teeth when filing soft materials such as aluminium is to rub over the file teeth with chalk before filing. This will help prevent the aluminium from sticking in the grooves.

Sharpening

Sharp tools are good tools the saying goes. (or something like that) One of the most annoying sharpness issues for me is blunt hand taps. Cutting internal threads is a breeze with sharp taps. Blunt ones just make me swear. I won’t buy plain carbon steel taps. Yes, they are cheap, but false economy in my opinion. They are only good for cleaning existing threads that are full of dirt or have minor burring. HSS (High Speed Steel) taps cut and keep sharp and when they have served a long and distinguished life they are still good for cleaning out threaded holes.

When they do eventually lose their sharpness you can resharpen them with a little care and a steady hand. Use a mounted point (that’s the correct term for a wee grind stone on a steel spindle) in a pneumatic die grinder or a Dremel tool. Use a mounted point with a cylindrical shaped stone about the same diameter as the flute or trench that runs along the tap. Try to take about the same amount off each row of teeth and undercut the teeth so that there is a “positive” rake to the cutting edge. When a tap has eventually served all of its useful life it can be ground into a handy centre punch.

Sharpening stones – the big flat ones- are useful for maintaining the sharpness of tools such as chisels and plane blades. (I know, this article is about the metalwork workshop, but hey, we are all flexible and can tackle all sorts of materials, right?) Inevitably they lose their flatness and develop depressions and grooves. Of course I understand that this would not happen to you, it’s when you lend it to someone else! One way to get it back to flat again is to us a piece of coarse sandpaper on a flat surface. Sandpaper with Silicon Carbide abrasive is better than Aluminium Oxide for this. Rub the stone backwards and forwards over the sandpaper until its surface is flat again. It will of course only be as flat as the surface under the sandpaper, so find the flattest you can. Use a sheet of glass if you do not have a piece of suitable steel.

Blind Bushes

Removing bush type bearings from blind holes is always a hassle. Understandably things are made to a price and slapping a bronze bush into a blind hole is easy for manufacturing, but has no regard for future servicing. I have had to extract many bushes in order to replace them when reconditioning machinery and on a lot of those occasions the bushes have put up a fight.

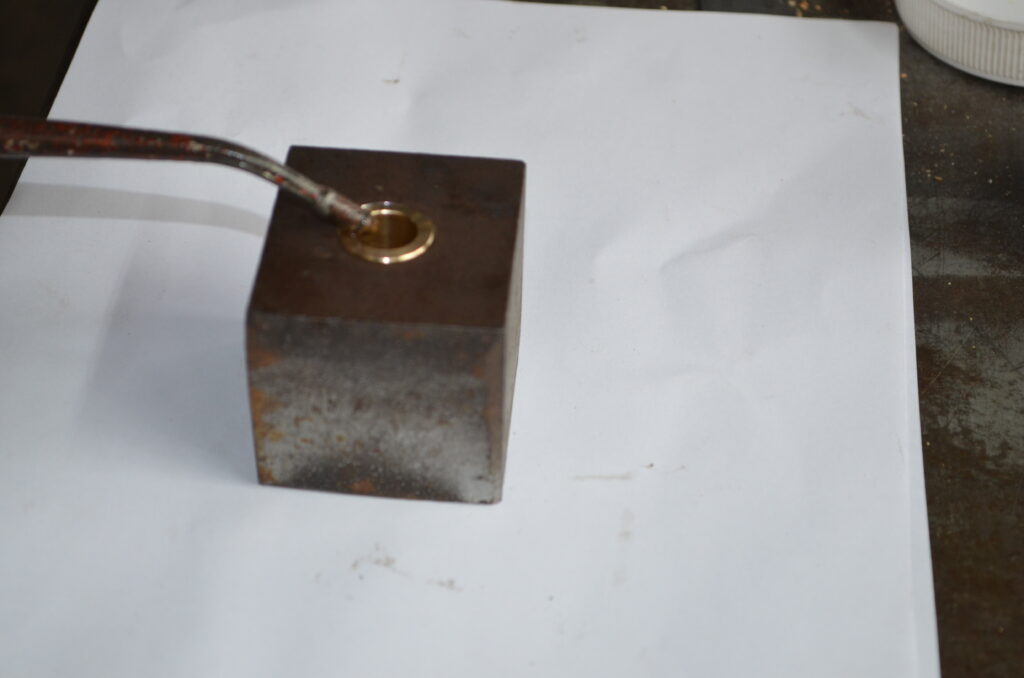

However the first and easiest way to get them out is to apply some basic hydraulics. This involves popping the bush out using a solid pin that is a close fit in the bore of the bush and some oil. The oil does not have to be anything special, but one with some substance is best, say SAE 30 grade or higher.

First nearly fill the hole in the bush with oil, leaving enough space to the top to start the pin into the hole. The solid pin should be a good close fit in the hole. Ideally use a dowel pin or some stock size silver steel rod. Put one end of the pin into the bush and give it a good whack with the hammer. Hydraulic pressure created will get under the bottom edge of the bush and push it up. It might take 2 or 3 hits. Oil will splash about, so perhaps put a rag loosely around the pin. In some cases where the bush has worn too oval, the fit with the pin will not be good enough to contain the pressure so you will have to resort to slitting and collapsing the bush or even drilling it out, but give the hydraulics a go first. It is easy and the result is good.

Stamping

I don’t mean stamping your feet and shouting unprintable words to no one in particular when a mistake is made, or when a speeding hammer has a collision with your thumb. I mean those punches – Number and Letter stamps which are a nice way to permanently label or mark metal items.

Certainly much neater looking than freehand grinding with a die grinder. However to get all the stampings in a tidy line takes more than just a good eye. Some people use a piece of masking tape stuck to the surface and line up the back of the punch with that by eye. I am sure this works but I prefer to use a piece of flat steel or wood for that matter clamped to the job and I hold the punches hard against that. The only eye work needed is the spacing between the letters. The small amount of time to set up in this way is certainly worth it to produce a far better looking result. (and reduces the need for some of that shouting mentioned earlier)

See part 2 of this series, elsewhere on The Shed website