Coppice craftsman Bill Blair on crafts as arts

By Nathalie Brown

Photographs Derek Golding

What is coppicing?

Coppicing is an ancient way of managing woodland. As the Hampshire Coppice Craftsmen’s Group website in England explains (http://www.hampshirecoppice. co.uk), “Many British broad-leaved trees including hazel, chestnut, ash, and oak can be coppiced. Coppicing means cutting the tree or bush down to the stump.

The plant then regrows, producing multiple stems called rods or poles. These can then be harvested and the poles converted into a wide range of products.” North Essex woodsman Andrew Basham with “30 years of experience with greenwood crafts” notes (http://www.coppicedesigns. co.uk) that multiple new shoots can appear from the stump or stool in the growing season after a tree is felled. “After a number of years, this lengthy greenwood can be harvested on a rotation of perhaps seven years or so and used for creating traditional woodland products. The cycle begins again with the emerging of more new shoots, an endless supply through the lifetime of the stool.”

The coppice where it starts

A coppice craftsman

It’s a radiant blue winter’s day. The frigid wind is sifting through the match lining in Bill Blair’s shed at the edge of the Oamaru Harbour while the coppice craftsman puts together a plate for his afternoon smoko. He eats half a muttonbird and two slices of sourdough bread, wipes his lips, and settles down to talk.

Asked why he has spent the best part of 20 years producing garden trugs, besom brooms, bentwood log carriers, wooden pitchforks, and rakes, he says he’s always had an inbuilt love of wood, of trees and the desire to work with his hands. “I was brought up on a farm in North Otago and in the Moeraki village. My parents valued things like gardening, sewing, and cooking, and being self-sufficient. And those values were inculcated in me.

In those days woodwork was still valued as a school subject although it was an activity for what they called ‘less academically gifted’ students. “But they still have craft colleges in Germany and France where traditional crafts are given more status and it seems pretty obvious to me that it’s important that people are able to make things with their own hands. “I think most crafts are an art in themselves. I like hand-making useful and good-looking items out of products that are locally available and might otherwise go to waste.”

Traditional woodworker Bill Blair holding finished trug. He also enjoys wearing traditional clothes

Wardrobe

Bill’s wardrobe is another example of his attraction to useful and good-looking things that might otherwise go to waste: most of his clothing comes from secondhand shops or are the direct hand-me-downs from previous generations. “Initially my dressing in late-19th, early 20th-century style had to do with the heritage revival in Oamaru. But I then became interested in the way we manufacture clothes, how fashion evolves. I used to work on oil rigs in my youth, but I wouldn’t have believed that in the year 2014 most of the population would be getting around in clothes made out of oil, which is what most of the artificial fibres are made from. “The natural fibres that we grew up with—wool and cotton and hemp— are warmer and easier to clean, they don’t smell as much, they look better as they get older, not worse.

And there is the association with the artisans’ philosophy—a lot of the traditional fabric is still manufactured in the traditional way; the best example being Harris Tweed, which is being kept alive as a luxury product. “It’s produced by hand, fetches a premium and allows people to maintain their lifestyle in the Scottish highlands and islands, working hand looms to produce high-quality material.

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

What I wear

“Today, because it’s so nippy here in this uninsulated shed, I’m wearing locally handmade boots, New Zealand-made woollen socks worn by most farmers and labourers, pink woollen long johns given to me by a friend.

My father’s farming friends used to wear ones like these, so I look more like my father and his generation. I’m wearing twill trousers from a trad shop in London. It’s the first pair of these I’ve owned. “Normally I wear traditional, woolen saddle-tweed trousers in the winter; a woollen long john singlet, of course. It once belonged to the now-deceased father of a mate. “On top I’ve got a collarless cotton shirt and a heavy, woolen New Zealand-made bush shirt.

My partner Ursula collects them from the op shops for me. Made by Lichfield which doesn’t exist anymore because everyone’s wearing that plastic oil-based clothing. “I wear my Harris Tweed jacket uptown and a traditional, 19th-century wide-brimmed cheese-cutter cap which Ursula made from Harris Tweed she bought years ago. We share an interest in the craft of tailoring.”

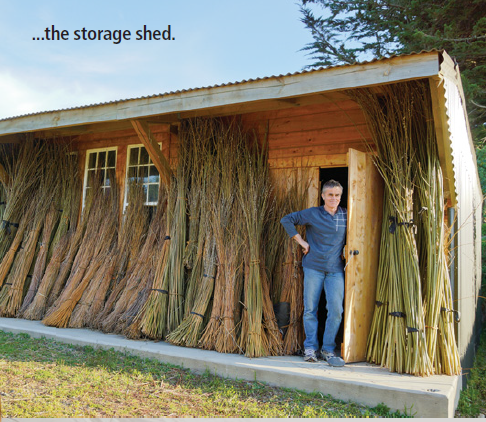

Drying the willow poles

Modern

All the same, Bill sees himself as a thoroughly modern person. He loves computers, new technology, science; he enjoys visiting other people’s sheds because he’s interested in the workings of modern workshops and machinery.

The work he took on in his younger years gave little indication of where he would find himself in his late 40s. He studied law at university but messed around too much and didn’t graduate. For the next 25 years or so he worked as a slaughterman, a wool presser on shearing gangs and a roughneck on offshore oil rigs.

In the mid-90s he got involved in heritage Oamaru, was inspired by woodworker Lindsay Murray (“A man of many sheds,” The Shed, Dec 07/Jan 08) and decided to make a modest living working with hand tools and wood. His shed is one of a group of four rustic red weatherboards and corrugated iron

Using buildings erected by the-then Oamaru Harbour Board in the late 19th century for harbour and quarry maintenance. They were used as utility sheds until the 1970s when the harbour ceased to function as such. The Oamaru Borough Council, and subsequently the Waitaki District Council, took over the land but didn’t have a use for the buildings so they allowed a local man, Ken Mitchell, to take them over. The idea was to house a number of craftspeople and over the years the sheds have been the workplaces for three or four different stone craftspeople (there is a quarry site on the harbour front) woodworkers, a boat builder, a traditional blacksmith. “But at the moment there’s just me,” says Bill. “We need more. The forge is still there, waiting for a smith.”

Heating willow in the steam box

Sheds

He moved into his first shed on the Oamaru harbour in 1998 and has been in his present one since 2006.

It measures about 6×8 metres in the main space with a little foyer to display his wares. The structure is a basic timber frame with corrugated iron cladding on the walls and roof. Most of it is matchlined with tongue and groove but some sections of the walls are lined with 19thcentury wallpaper from a time when it was a sitting room with a fireplace for the foreman.

It’s very cold in winter. Bill bought three former secondary school woodwork benches at a secondhand shop and raised them on blocks. “One’s an engineer’s workbench,” he says. “I’ve got one of those woodwork benches in my workshop at home and I’ll probably retire to that when I turn 65, which isn’t very far away. I have another in my workshop at Ursula’s place for weekend work. So I have three sheds.”

Many of Bill’s tools are over 100 years old

Old tools

He is very orderly, although he says he’s not. Many of his tools are more than 100 years old. He says that, by some modern ways of thinking, it’s a bad idea to keep a tool for so long when you should be buying a new one every year or so and throwing the old ones in the dump.

Actually he finds that some of the older tools are better manufactured and work more efficiently. Hanging on the back wall is the basic tool kit for traditional woodwork. There’s a selection of hand saws: crosscut saws, rip saws, tenon saws, a large selection of Stanley and Record hand planes in various sizes for jointing and smoothing and jack planes for roughing out.

There’s a large side axe and a block knife. He does a lot of shaping work with side axes and chisels. He uses old hand drills to make holes for nailing the trugs together. There are drawknives and braces and bits; hammers. Of course, there’s plenty of screwdrivers, sash clamps and G clamps.

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

Shaving horse

“The shaving horse was the very first implement I made in 1997 when I decided to become a shed man. I built it from instructions I found in an American book, modeled on a Swiss traditional wooden bucket maker’s shaving horse.

It’s a sitdown, foot-operated wood clamp. “It clamps the wood but releases it quickly—with your foot providing the pressure—and allows you to use a drawknife and a spokeshave to shave wood rapidly and accurately. “Then I made my foot-operated pole lathe for turning wood based on the original system, presumably invented thousands of years ago. It’s operated by a foot pedal with a leather-and-rope cord round the wood to cause it to rotate.”

Whittling feet…

…and poplar planks to shape

Hand-planing poplar planks for trug base

Electric

Bill boasts that he has a small electric lathe now and he’s got a bandsaw at home, which he thinks is the best electric tool ever invented. “Originally bandsaws were powered by water and wind and steam. But I love my electric bandsaw. They’re very safe compared to a table saw and circular saws. Even an electric lathe can be quite lethal but you have to be really hopeless to damage yourself with a bandsaw.

I’ve also got a chainsaw and regular crosscutting saws for tree felling, and axes, mauls, and wedges for splitting wood. “As I get older, I get more interested in electric tools but it’s nice to have that grounding in hand tools.

If you’re brought up with power tools, you get into the habit of using them and you might be unaware that you could do a particular job faster and more pleasantly with a traditional hand tool. “You can spend a lot of time setting up your power tool with jigs and clamps, all to do one tiny little job that you could have done in ten seconds with a drawknife. So I think all woodworking—all crafts—should start with learning how to use hand tools. Then later on you can find out what power tools might be more advantageous.”

Planks dunked in boiling water become pliable

Soaked, rubbery planks bend easily

Test

Today

Would he recommend this way of life to anyone today? “If I was giving advice to my younger self in my 20s I’d say: start earlier. Travel around; visit as many craftspeople as possible; read as many books as possible; visit as many websites as possible; try out as many crafts as possible; do workshops and focus on one or two and really work at getting good at it. And try and do that before you’re 30.

“But it’s hard for young people to see how to make a living at it. You have to be quite courageous because you are not going to be rich. And you have to work hard. You have to enjoy work for its own sake. “Believe me, working on an oil rig and slaughterhouse is a pain in the neck and not enjoyable. But I think everybody should be able to have the aim of being able to create work for themselves which they really enjoy, so when they go to work they think that’s the best thing they could be doing with their day.”

Trug handles and frames

Building up base

Last planks

Trim

Measuring feet position

Signing the work

Making a trug

Bill makes a variety of trugs from miniature to large. He explains

1. For a large trug, I first go up to the coppice and harvest green willow poles two-metres long and about 3-4 inches (75-100 mm) in diameter.

2. I split each pole in quarters with a froe [a froe is a simple heavy blade with a socket at one end for a handle and is used to split wood along the grain]. Then I do some basic adze work to trim them down to size,

3. I continue the rest of this work on the shaving horse with a drawknife and the spokeshave.

4. I shape the handles and rim for their lengths.

5. Then I dry the willow on the roof at home in the sun. The wood needs to be dry to bend and also the sun darkens the bark—it goes from green to a nice brown-red colour. When they’re dry, ironically, I soak them in a bath of water for four days to make the bark pliable.

6. I heat them in my steam box here at the workshop and bend them into bending frames.

7. They dry there for a few days till they’re ready to be taken out, cleaned up, handle and rim nailed together; then they’re ready to be assembled as a trug.

8. The planks and the feet are prepared from poplar wood. I bandsaw the poplar planks roughly to size at home, then bring them in here to my workshop.

9. I hand-plane them smooth and to perfect thickness on the bench with my 100-year-old Stanley hand plane. It has to be razor-sharp so that the wood comes off a glossy, smooth, mirror finish.

10. I give the planks a brief soaking in water and as I’m assembling the trug I dip them in boiling water briefly, just enough to allow me to bend them. They become quite rubbery and pliable for a few seconds. Just enough to get a nice, almost right-angle bend.

11. Then they are ready for nailing in place on the trug.

12. I pre-drill the holes with a hand drill, nail in a copper rosehead boat nail, and clench it over in the traditional way: bending the nail, cutting it off, and bashing it down into the wood.

13. The last thing to do is put on the feet, which I also shape on the shaving horse with the drawknife and the hand plane and my Swedish, laminated steel whittling knife.

14. Then it’s a matter of tidying up, cutting off the ends of the planks, and signing my signature with a hot-wire poker machine. I wax the handle and that’s it, finished

A trug costs between $50-$120 and they are available through the website: www.coppicecrafts.co.nz

Finished trugs

Bill Blair…create work that you enjoy

Coppicing in New Zealand

Bill’s main coppice crop is bark-covered poles for the handles and rims of the trugs.

In England, they would use sweet chestnut or ash but these trees don’t grow here so Bill uses coppiced willow. A few years ago he made contact with the Canterbury Regional Council in Timaru. They’ve maintained willow coppices round the whole region for river planting. The coppices are somewhat under-utilised so the council was happy for him to co-manage one of their coppices at Kurow. It’s about 1.5 hectares.

Before that, Bill was scavenging the willow poles along the riverside. North Otago Metals, who own a lot of the Waianakarua River, gave him the key to their kingdom and let him scavenge their naturally coppicing willow along the river.

Bill says, “I’ve done two days hard labour at the Kurow coppice for my main cutting this winter so I’ve cut 30-40 stools down to the bare basics. I’ve got them growing in steps so I need to grow them on for about four to eight years. But I do selective cutting of poles through the rest of the year as I need. “When you do main cutting, you cut down all of the poles off a particular stool—or a stump—to allow it to re-grow.

And you need to do that in the middle of winter so it gets a full season of growth before the next frosts come. But for the rest of the year you can selectively log off a stool and it sprouts new shoots.” He says coppicing as a general practice doesn’t really exist throughout New Zealand.

The regional councils refer to them as willow and poplar nurseries. They were established by local catchment boards throughout the country in the 1960s-70s. When regional councils were established after catchment boards were abolished, they took the coppices over by default but many of these have ceased to exist. “They’ve been bulldozed and turned into dairy farms,” says Bill. “But some of the old catchment board staff are still employed by regional councils and they believe in willow as a conservation measure for riverbank stabilisation and catchment planting. It’s only because of their enthusiasm that the coppices are still there. They’re just not resourced as well as they used to be.”