By John Stichbury

When I left school I took on an apprenticeship at William Cable in Wellington. Unknown to me at the time, this opportunity would lead to a life-long interest in model engineering.

My apprenticeship gave me a wonderful grounding in all aspects of engineering. I began in the tool room under the guidance of a great engineer and tremendous mentor who was prepared to take the time to pass on his knowledge and expertise. This definitely was the fuel that ignited my interest. The next step was time spent in the pattern-making shop at the foundry which gave me the knowledge of how to make small alloy castings in my home workshop.

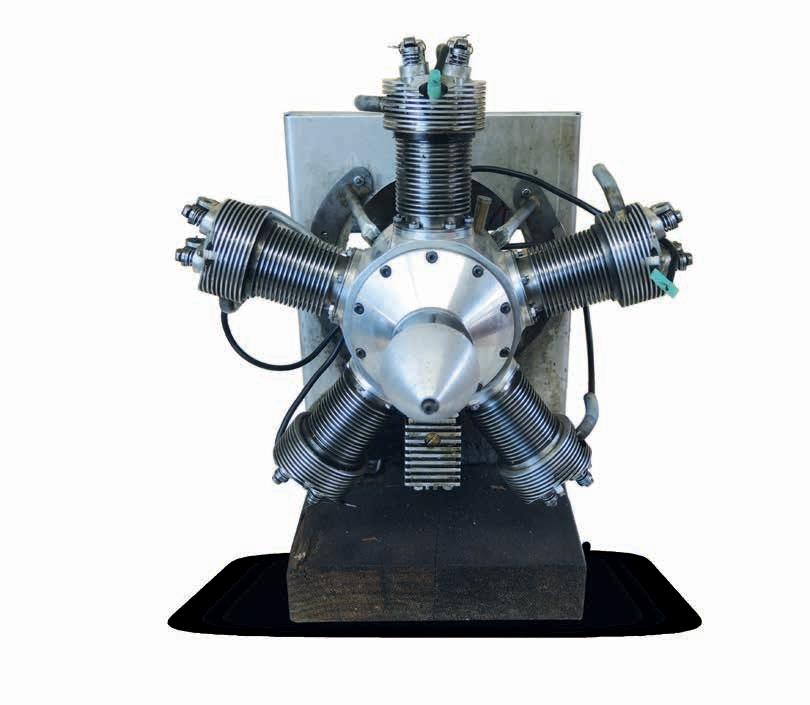

1: A Morris Minor side-valve engine from the mid 1950s. The engine is 15cc, water-cooled and runs on 91 octane with spark ignition 2: A 1930s Kinner k5 cylinder rotary aero engine over-head valve used in trainers prior to World War II.

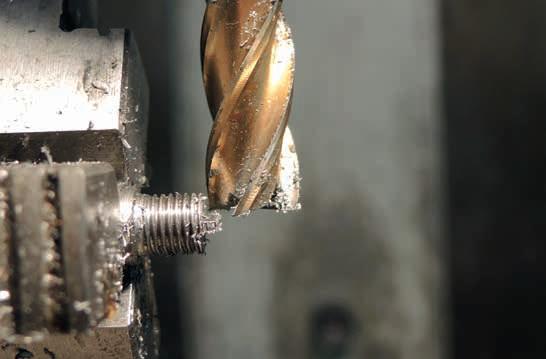

Engine bearings

In the general engineering shop I learned how to weld with both gas and electricity. It intrigues me to realise things have greatly changed since then. One particular skill I acquired was learning how to re- metal engine bearings with white metal then machine them back to size. These bearings ranged from Austin 7s through to half-ton ship bearings—a broad spectrum.

As my interest was really in the mechanics of what could be achieved in the tool room in my spare time, I began making miniature models for myself. This interest has continued and I have gathered numerous small tools over 50 years. I have a well-equipped workshop with two mills, two lathes and a large selection of hand tools and I spend many hours there.

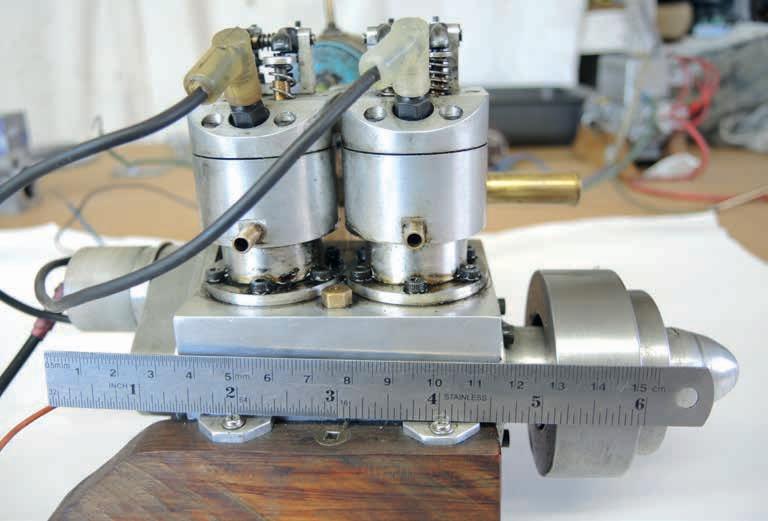

1: The same Morris Minor engine assembled 2: Frank Whittle’s first petrol aero — an 8-cylinder petrol engine designed and built for the RAF in 1938 3: A 12cc overhead-vale marine engine built without castings 4: A double-acting, single-cylinder steam engine built from scrap brass.

Over the years of making many different models—including steam trains, stationary steam engines and small jet engines—my interest and focus has been on internal- combustion engine models. All my engine components, including gears, pistons, rings, crank shafts, etc, are machined from scrap.

I realised miniature spark plugs have become increasingly difficult to source, not to mention very expensive, so I decided to make my own. Trial and error ensued and then finally success.

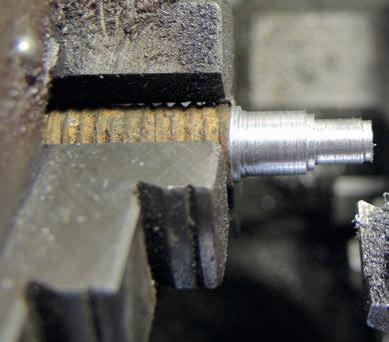

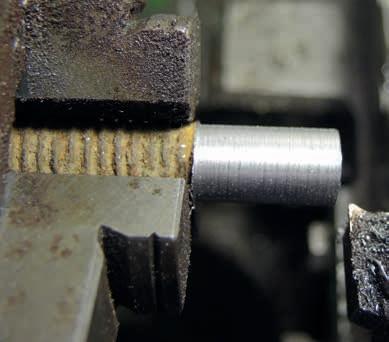

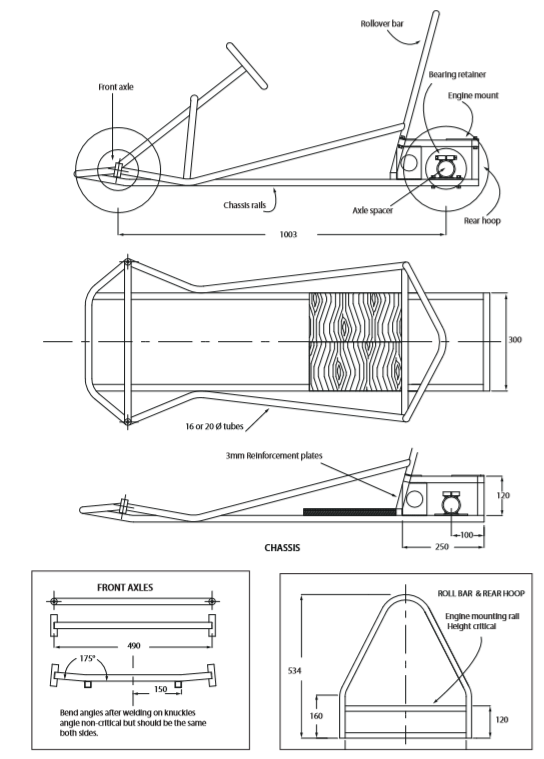

1: The beginning of making the outer body — a piece of old mild steel was machined to the diameters to take a 1/4 inch (6.35mm) thread and a hexagon 2: The finished diameters ready for threading 3: The completed body ready to be screwed into a mandrel in the milling machine 4: The hexagon being milled in the dividing head on the mill

DIY Spark Plugs

You can still purchase mini spark plugs from overseas but being able to make your own means you can vary the thread depth to suit your own designs and you are saving in the vicinity of $40 each.

The basic material components of a spark plug are as follows:

- a piece of scrap mild steel

- 1⁄4 pint (118millitres) old engine oil

- Corian off cuts (sourced from a kitchen manufacturer)

- small piece of brass

- 1 mm tungsten welding electrodes

1: The completed body ready to be turned round in the lathe and counter bored to a depth that would leave a flat bottom to allow subsequent milling producing an electrode

2: The electrode being milled to the required width

3: The components partially assembled. The metal bodies were heated with a gas flame until blue and dunked in old oil producing a black lustre

4: The completed plugs alongside a short-reach champion spark plug

Method

First I machine the mild steel scrap to take 1⁄4 inch (6.35mm) x 32 model thread. I transfer it to the mill and machine the blank to take a 5/16 inch (7.94mm) hexagon. Reverse the piece on the lathe and mill a 4.8mm blank hole for the insulator.

Reverse the body again and mill the end to form an electrode.

When this is completed heat the body in a gas flame to a blue colour and then quench in old engine oil. The old oil produces a black lustre on the surface finish.

Take a piece of Corian and cut it into suitably sized lengths. Machine it into a round tube 4.8 mm diameter and drill a 1 mm hole the full length to take the electrode.

A small brass cap is placed on top of the electrode and welded so the ignition wire can be attached. Once all components are thoroughly cleaned the electrode can be glued into the insulator with superglue. Fit a suitably sized gauge between the two electrodes temporarily and glue the insulator into the body leaving the required spark plug gap