The smallest, chief engineer Mike Jackson, gets into the wing

A new life for the big cat

Anyone flying into New Plymouth airport may look twice at a hangar on the western end of the airfield with an unusual tail of a large aircraft poking out.

Few would realise what’s within: ZK-PBY, a 1944 Catalina flying boat, the only airworthy one in New Zealand and a remarkable aircraft with a remarkable history.

The Catalinas were nicknamed “Dumbos” when they came out from the US Consolidated Aircraft Corporation during World War II and justly so. A flying elephant is an apt comparison.

These big machines have a grace of their own and are an unusual shape. They’re an unwieldy looking aircraft with a 104 foot (31.7 metre) wingspan—bigger than the wings of a Boeing 737 jet. They are 63.8 feet (19.45 metres) long and 20.1 feet (6.15 metres) high. Inside the hangar the Cat, as it’s affectionately known, is undergoing major repair work.

This is a shed restoration with a difference. If you think restoring an old car is a big job, this project takes the cake.

One of the key players behind getting the Catalina to New Zealand is Brett Emeny, who said the project has great support from the organisation that owns the aircraft, the New Zealand Catalina Preservation Society. Volunteer work, support and donations keep the ball rolling.

going, going…

…inside

Brett Emeny of the New Zealand catalina preservation society

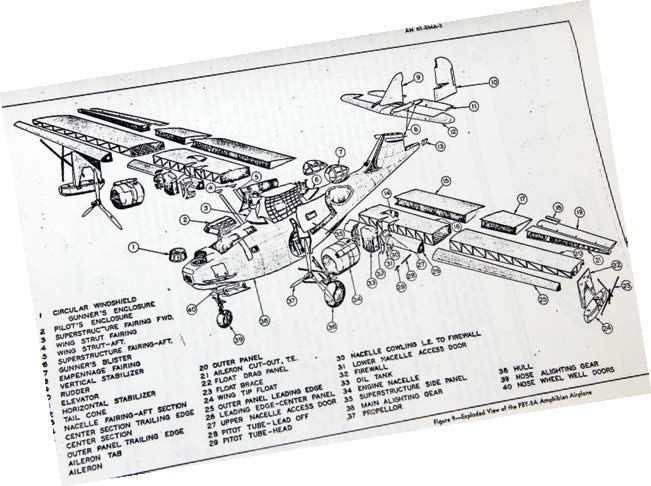

exploded view

Aircraft expert

Two retired aircraft engineers (who refuse to retire) have been working four days a week on the aircraft since June 2013 and there’s a lot of work still to do. They hope to have the job finished for the Catalina to fly at the Omaka Classic Fighters Air Show at Easter in the South Island. Mike Jackson, at a sprightly 75, is head engineer on the project. Mike joined the Royal Air Force (RAF) as an apprentice in 1956, aged 19, and has worked on many aircraft, mainly helicopters ever since. He decided to retire ten years ago but that didn’t work. These guys have avgas in their blood.

Don Barr goes back a bit further. He joined the Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) in 1949 to begin his aircraft engineer training. He was aged 18. His eight years with the RNZAF included two years on a peacekeeping tour in Cyprus. He did his time in the 50s working on Vampire and Meteor jets and is very familiar with Catalinas. Retirement was considered 20 years ago but there was no stopping Don.

He has worked on helicopters and fixed-wing aircraft for the last 20 years and when the New Plymouth syndicate picked up a Vampire jet, Don was the obvious man for its restoration.

He works on every aspect of the Catalina rejuvenation except for electronics.

Retired New Plymouth engineer Athol Rowe, an original member of the Catalina society, also works on the aircraft. He works as a volunteer and also makes up aluminium parts in his workshop.

The fourth member of the team when we visited was Dave Clement who calls himself the gopher. When I was there to check out progress, he was stripping paint off the wing fabric.

Lake Taupo takeoff. The Ctalina in a previous incarnation

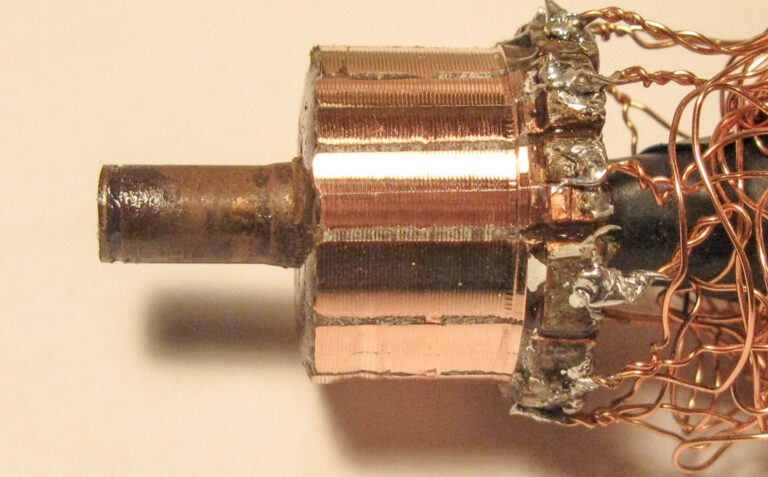

Aluminium corrosion is the greatest problem

New parts are drilled to match the rivet holes in the wing

Massive

So what’s involved in a project of this size? For the volunteers to work on the massive wings, the whole aircraft was surrounded by scaffolding. One wing had to be removed for the job. After work on the wings was complete, the team was to move onto stripping the paint and repairing the fuselage. Then the annual inspection of the aircraft would take place. This had to be followed by work on the systems—the engines, undercarriage, floats etc. The propellers have to be removed for their five-year inspection.

Mike said aluminium corrosion is the biggest problem. While some areas can be patched, the corrosion in some strips along the wings mean new parts must be made and then drilled to match the rivet holes on the wing. This involves drilling thousands of holes and then riveting the new piece in place. Riveting is a two-man job, one on the air-powered rivet gun and one holding a dolly in place on the other side which is sometimes deep in the wing frame. Squeezing into the wing to do this is not always easy. Mike said they try to keep the Cat from landing in salt water to avoid too much corrosive damage. Mike and Don work off photocopied manuals of the original 1940s maintenance manuals.

These even include details on how to patch up bullet holes. It’s slow and painstaking work. New

parts have to be made, some locally, but some extruded parts are especially made in the United States with special dies. They have managed to pick some parts from old Catalinas scrapped after World War II.

The Cat is held together by hundreds of thousands of flathead or roundhead rivets of varying sizes and the aircraft is massively strong. The wings are constructed of anodised aluminium alloy with fabric on the back trailing edge. Inside the wings are located many angled stiffeners, only 50/1000ths of an inch (1.27 mm) thick. Some of these struts will need to be replaced. The common thickness of the aluminium alloy used in the Cat is 25, 35, 40 or 60/1000ths of an inch. This industry hasn’t gone metric.

Any replacement aluminium or patches must be the same thickness or thicker than the original.

The area under the wings is strengthened to carry the ordnance—up to 4000 lb (1812kg) of torpedoes, bombs, anti-ship mines or depth charges.

The original material on the back of the wings of the Cat, and of many other World War II planes, was Irish linen. This was sewn or riveted to the frame, shrunk (doped) to make it tight and then painted. Linen has today been replaced by a synthetic material called ceconite.

The retractable floats on the tips of the wings have been re-built.

Mike said while modern aircraft have carbon fibre components and are built with special adhesives, this project requires experience of the old forms of construction.

“Aviation has changed

considerably in the last 20 to 30 years. Decisions on what can be done in a project like this were once made by two engineers. Nowadays there are way more rules

and regulations.”

With the work on the fuselage and wings almost completed, the crew are now looking at some fabric repairs and the big job of painting the aircraft. The Cat will then be re-assembled ready to take to the air again.

Hundreds of thousands of rivets hold the plane together

Riveting is a two-man job for Don Barr(left) and Mike Jackson

“Gopher” Dave Clement prepares for the big paint job ahead

New struts

Synthetics ceconite now replaces Irish linen as the wing fabric

Specifications

The PBY Catalinas are a long-range aircraft. They can fly 2544 miles (4095km) in one hop and this aircraft was operational with the Canadian Air Force, used for carrying out maritime patrols, sometimes equipped with depth charges, torpedoes or bombs.

They could fly non-stop from Auckland to Darwin and the longest commercial flights were from Perth to Colombo, a distance of 4116 miles (6625km)

Their long range meant they were excellent for reconnaissance. It was a RAF Catalina that in May 1941 located the German battleship Bismarck, leading to its sinking by allied warships.

Catalinas were also credited with destroying 40 U-boats during the war.

They also saved the lives of thousands of downed aircrew and sailors from sunken ships. According to the Wiki website a PBY Catalina rescued 56 sailors in high seas from the sunken heavy cruiser Indianapolis. When there was no more room inside the aircraft, they tied sailors to the wings with parachute cord.

They have twin radial Pratt & Whitney engines generating 1200 horsepower, the same engines that power the famous DC3. Each supercharged engine has 14 pistons and 28 spark plugs.

The New Zealand Air Force operated three Catalina squadrons with 56 of the big flying boats in the Pacific from 1943 to 1953.

The Catalinas operated with No 5 and No 6 Squadron and No 3 OTU, based at Hobsonville and various points in the Pacific. They were engaged in anti-submarine patrols, shipping escort, air-sea rescue and transport roles. Unlike many other lend/lease aircraft, the Catalinas continued to be operated after World War II because they filled a vital role in South Pacific communications.

They were sadly all scrapped after the war. The constant landing in salt water didn’t extend their life span either.

Production of the PBY Catalina began in 1936 but of the 4051 built only a few dozen airworthy Cats remain, according to the Wiki website.

PB stands for Patrol Bomber and the Y is the code number for Consolidated Aircraft.

Challenge

Brett said they are a challenge to fly. All the controls are manually operated—nothing is powered as in today’s aircraft—and they operate on 1930s technology. He said he has sat with modern commercial pilots flying the plane and they have a hard job.

“These guys usually have sweat pouring off them with the effort of working the controls and concentrating on the job. It’s not easy. There’s a lot of hand-and-foot coordination required to control the Catalina.”

Mike showed us through the cockpit. The controls are original and the instrument panel is virtually the same as it was when it came off the assembly line.

The Catalina cruises at 115 knots

(212 km/h) and it needs 1000 feet (304 metres) of runway to take off. On the water they need to reach 86 mph (139 km/h) to lift off.

They land more easily on water but still need up to 3000 feet (915 metres) of reasonably calm water to touch down. Dead calm or glassy water can be tricky for takeoff as the aircraft can “stick.”

Most Catalinas have floats instead of wheels, but this aircraft has both. Fully laden, it can weigh more than 16 tonnes.

Former air force engineers Mike Jackson(left) and Donr Barr with the maintenance manual

Don Barr and John Emeny fitting the fabric trailing edge section

To New Zealand

Getting a Catalina to New Zealand was not without difficulties. A syndicate for this purpose was formed from a group that purchased a 1958 Vampire jet which arrived from Switzerland at the same time as the Catalina 20 years ago. Brett says he simply had to assemble it. He and the Vampire can sometimes been seen, and definitely heard, screaming across the Taranaki skies. Anyone winning Lotto should consider getting their own Vampire, surely the ultimate means of transportation for the discerning gentleman. But I digress and that’s another story.

The syndicate searched the world looking for Catalina and initially found one in the US. While it was on its way to New Zealand in 1994, disaster struck. It suffered engine problems and had to land on the water in pitch darkness near Christmas Island in Kiribati in the Pacific. The rough landing caused some damage; the Catalina sank and was lost. Luckily the crew were picked up.

As the website of the New Zealand Catalina Preservation Society explains, the search began again and the current aircraft was found in Zimbabwe. It was originally delivered to the Royal Canadian Air Force in March 1944 and operated on anti-submarine duties. It was struck off on June 27, 1947 and no records were available until it was converted to 28-5ACF status by SALA in Costa Rica in 1955. It was then used to fly tourists up the Nile, billed as “The Last African Flying Boat.”

The syndicate purchased it for $500,000 and in 1994 it was flown successfully to New Zealand where it took six months to get it certified under New Zealand regulations. It has now been operational in New Zealand for 20 years. It operated a while from Lake Taupo and has toured the country.

“It was like the old days of barnstorming,” said Brett. “The Cat always attracts a lot of attention. People of all ages love it.”

The current in-depth inspection and repair is aimed making the Cat airworthy for some years to come.

Peter Vause’s black and white Russian Yak trainer

Volunteers welcome

ZK-PBY is now owned by, and is being brought up to scratch by, the non-profit New Zealand Catalina Preservation Society. The society has members from all over New Zealand.

On the website it says the society is supported by members and active volunteers who manage the ongoing support required to keep this rare and famous World War Two flying boat as a unique aviation heritage project. Another aim is to honour New Zealand veterans with flyover appearances during commemorative military events.

A percentage of the cost share flying undertaken by friends of the Catalina has also raised more than $30,000 for the Child Cancer Foundation.

Mike and Don said anyone interested in volunteering their time to help restore the Catalina can contact them. Visitors are welcome. There’s still plenty of work to do. Also, anyone interested in joining the society and getting involved can check out the website at www.nzcatalina.org.nz/

Brett said the whole project will cost about $300,000 and the society is still to fundraise the final $100,000.

“It’s a big job but we’re on the downhill run now,” he said.

Membership is open to anyone in New Zealand and overseas with interest in Catalina flying boats and New Zealand’s aviation heritage. There are different levels of membership.

Big Boat

Well-known weatherman and pilot member Jim Hickey has a love of old aircraft and especially the big Catalina. He has flown in it and taken the controls briefly.

Asked how it handled, he described it as “flying a four-storey building lying on its side with a couple of wings attached. It’s really just a big boat. Despite that it is well-balanced and very responsive. It’s not unlike flying a DC3, but it’s heavier. It’s a great sound when those big Pratt and Whitney engines fire up.”

He said the dynamics of flying from water to air are very different. “The tricky part is getting the air flowing between the water and the hull. It’s a unique aircraft.”

Jim first flew back in about 1988. He then took flying up again about 1993 and got his licence a few years later. His father flew Spitfires in Burma during World War II. “They were the real hotrods, the high-altitude Mk19 Spitfires. He flew photographic reconnaissance Spits—no guns, no armour plating, but nothing could get near them for speed and climb. They could climb at over 3000 feet per minute.”

Jim has his own Yak aircraft and is a member of the New Zealand Warbirds Association.