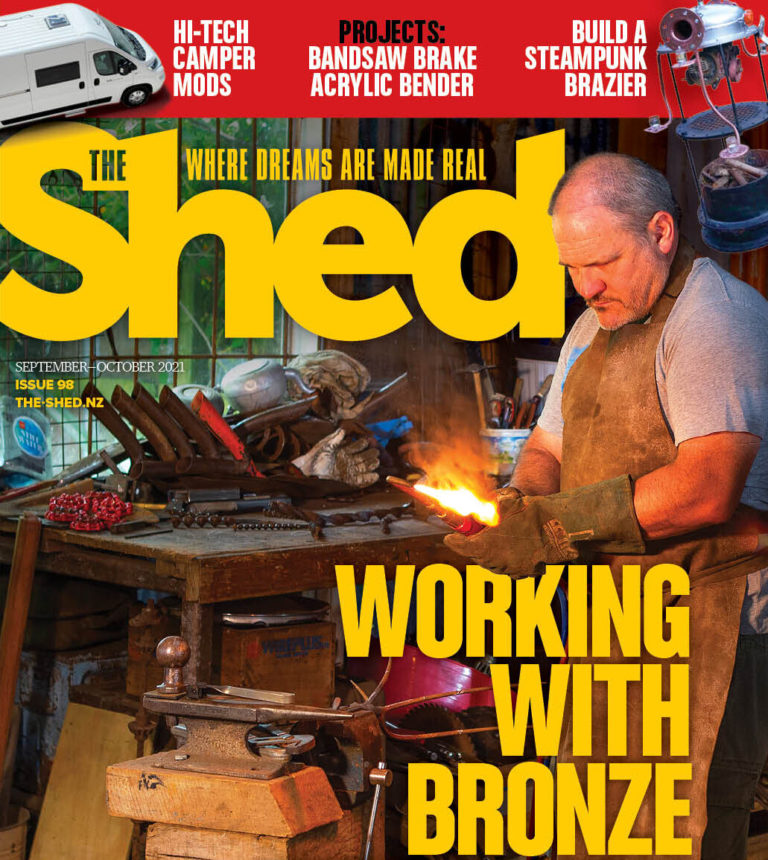

A fitter-welder uses his technical know-how and imagination to create works of art

By Sue Allison

Photographs: Juliet Nicholas

A silver giant sits reading under the trees while a woman stoops to pick a flower and a thin man cycles past on a penny-farthing. Nearby, an enormous corkscrew dwarfs a shed filled with welding paraphernalia. One glance around Allan O’Loughlin’s garden and it’s clear that this is the home of someone with a vivid imagination and the creative skills to bring it to life.

Allan, a fitter-welder and self-taught sculptor, uses the skills learnt in his trade to create works of art in steel. More than 60 of them are scattered around the 9000 square metre property he shares with his partner, Andrea, in Mandeville, 25km north of Christchurch.

Unlike most artists working in the medium, Allan doesn’t construct his sculptures by bolting or welding solid metal shapes together, but relies on the properties of molten steel to mould and fuse his forms.

His initial frameworks are simple structures made out of wire and builders’ reinforcing rods which he curves into shape using heat and a home-built metal former.

Molten metal

“They all start out looking like simple stick figures a kid would draw,” he says. Wire is then tack-welded around the skeleton to create a mesh-like hollow form. With the “bones” in place, the fun begins and Allan sets to work fleshing them out with layers of molten metal.

Steel is dripped over the framework using a MIG torch welder, the “hot-glue gun” of welding. “You couldn’t do this with an arc welder. It would take forever.” The gun is threaded with copper-coated steel wire to limit rusting and he runs it on CO2 as a cheaper alternative to an argon shield.

Not one for making or following rules, Allan tends to improvise as he goes along. Sometimes he cuts out shapes in plate metal or incorporates scraps lying on his bench in the molten mix. “There might be sheet metal hiding in them, you just can’t tell. They’re all welded over.” Some, such as the figure reading a book, have a scale-like finish which he creates by cutting sheet steel into small rectangular pieces and welding them as a skin over the surface.

Allan compares himself to a potter or glass-maker in that he transforms his material while it is in a malleable state. The process itself resembles making papier maché in the way he builds up layers over the wire frame, manipulating the surface before it sets hard.

“The great thing about steel is that you can cut bits off and add to it,” he says. “Most things work in the end and, if they don’t, you can always rehash it.”

“Allan compares himself to a potter or glass-maker in that he transforms his material while it is in a malleable state”

Zinc coating

He leaves some of his pieces to rust naturally and paints others with commercial rust-kill, which gives them a treacly burnt-brown finish. But most he takes down to one of the two big dipping baths in Christchurch to be galvanised, which leaves them with a striking silvery zinc coating.

Allan has built everything on the property himself, from the house, sheds and a cob cottage to the garden furniture, sculptures and machinery needed to create them. His central piece of equipment, outside his welding apparatus, is an old car hoist fitted with a crane-like device that enables him to lift up his sculptures and work on them at a comfortable height. “I bought the winch and track and made my own arm. It grunts and groans but does the job.”

But his favourite invention is his “spit”. The rotisserie-style spindle means he can mechanically turn his sculptures as he works on them. It has a reduction gear box and is operated with a foot control, leaving his hands free to weld. Moreover, it is fitted with a locking pin. “There’s a lot of weight in uneven pieces and the pin holds them so it doesn’t spin out of control. I built my spit about three years ago and it’s made my life so much easier.” Allan also made his own contraption for bending steel using an old piece of pipe as the lever.

“The rotisserie-style spindle means he can mechanically turn his sculptures as he works on them”

Inspirational

He has a ready supply of scrap metal. “I’ve got mates in engineering businesses so I get scrap steel from them. It’s amazing what you can buy with beer and whisky,” he says. “I don’t waste anything. I use every bit of steel I find lying around.”

Allan was first inspired by a sculptural work he chanced upon 20 years ago in Sydney’s Parramatta square which depicted soldiers in the trenches in World War I. “It was metal but had this pinched clay look. I came home and thought ‘I can build something like that’ and that was it.”

His inspiration often comes from images, mainly of dance poses, downloaded from the internet. He often elongates the limbs and exaggerates the human form. Not only does he like the artistic effect, but he says it is easier than trying to make them look realistic. “Before I start I can pretty much see it in my head,” says Allan, who sometimes makes a small maquette before tackling a big piece.

He takes anywhere from a few weeks to several months to make each piece, often working on a couple at a time. “I’m one of these people who doesn’t stick to a timetable.”

Allan uses an air-fed helmet when welding and goes through a lot of fire-proof gloves. His eyes, he says, are his most valuable asset followed by his hands.

Allan, who says he is often covered in bruises from lugging his sculptures around the garden in a sack barrow, is in the process of setting up lighting in the garden. “It looks unbelievable at night with the shadows,” he says. “I’ve lit a couple with fluorescent green lighting which is spectacular.” Others have 240-volt motors, operated remotely, mounted in boxes underneath. A galvanised form resembling wavy buffalo horns seems almost fluid as it revolves slowly on its base.

“It’s just for me. Another kind of man-cave, I suppose”

Planned gallery

Allan has exhibited at several events, including the annual Art in the Garden at Flaxmere, and lends out sculptures for fund-raising garden tours. While he sells his work privately, he doesn’t push sales and is reluctant to do commissions. “It makes it like a job,” he says. Even the gallery he is planning to build on the property is not a commercial venture. “It’s just for me. Another kind of man-cave, I suppose.”

Allan’s other passion is gardening and when he isn’t working with steel, he can usually be found tending the expansive property. “Sometimes I go out and do a bit of work to bring some cash in but otherwise it’s weld, garden, weld, garden. That’s my life. I love it.”

His “real job” involves installing conveyor systems, work which often takes him overseas. Wherever possible, he tags on trips to local art galleries. “I worked in England before Christmas and afterwards went straight to Paris and spent 10 days just going round the galleries.” He doesn’t regret having no formal training. “If you study somebody you become like them. I just build what I want to build,” he says.

“I couldn’t read or write when I left school. Art was the only thing I was ever good at. I was told I had about five disorders and back then they never really helped you. You just kind of fell in the dyslexic bin.” But, he muses, looking round his wonderland of sculptures: “I don’t know if I want to be normal.”

For the birds

Allan, who loves birds, is happy to accommodate them in his garden. Old gas bottles are put to good use as high-rise condominiums for starlings. He made each unit by cutting a hole in the side of the bottle and “sticking a wee roof” on top, then mounted them on a pole. “They used to nest in my shed but they don’t come anywhere near it since I made that.”

Nearer the house, a tall figure carries a cage on his shoulder. A piece of art in itself, it doubles as a safe feeding spot for small birds. Allan carefully measured the gaps between the bars so little birds like wax-eyes can fit through while larger ones, such as starlings and magpies, can only sit on top and watch in frustration. A door on the side lifts up so the feeding block can be replenished.