A Taranaki farmer tosses couches and water drums for fun

By Ray Cleaver

Photographs: Rob Tucker

Dave Hunger of Stratford is definitely one of those Kiwis-in-sheds happy to tackle projects they know nothing about in the first place. For his latest project, his shed was his whole dairy farm.

He has built a medieval trebuchet from scratch in the wide open spaces. The awesome medieval throwing machine-cum-catapult, with a 13-metre-long throwing arm and a two-tonne counterweight, can toss a 20-litre drum of water a distance of 100 metres.

Dave built it with no specs or diagrams to work from, just a few pictures on the internet and lots of trial and error. He dropped a few trees and used old tractor parts to create a massive machine that cost him only $300.

He has thrown a couch, flaming projectiles and pushbikes, and he’s working on increasing the range of the fearsome machine. It’s the ultimate boy’s toy; it is not much use but a lot of fun.

How it works

The throwing force of the trebuchet comes solely from the projectile at one end being driven by the throwing arm pivoting as the mass of the counterweight falls at the other end. The throwing arm is pulled down to raise the counterweight at the other end. With quick release, the falling weight provides the force for the arm. The throwing arm does not flex to provide thrust. The short distance between the weight and the fulcrum means the heavy weight falls quickly over a short distance, and the longer end curves up over a wide arc to fling the projectile high and a long distance.

Boys’ idea

The incentive for the project came from Dave’s sons, Josh and Andrew. The boys were jumping their bikes, and Josh (13) came up with the ultimate idea – throwing their bikes with a trebuchet, which they had seen in action on computer games. The boys started with a small trebuchet using stones, but it didn’t throw them far, so Dad got into the act. Dave checked out machines on the internet that were even throwing cars. The world record is a 630-metre throw. He was impressed and thought he would give it a go. He had some Lawsoniana trees he intended to drop, so he thought now was the time. He finds the Lawson trees were straight, and the wood is very flexible.

The two-tonne counterweight concrete block was once the back weight on a front-end loader. The main cost was $200 for a snig chain to secure the block onto the main arm.

“I wanted to keep the cost down, and it worked out fine, “ says Dave. “It was all trial and error. I did a scale drawing from pictures on the Net but had to work out technical specs on the spot.

“The main pivot shaft is an 80 mm steel axle off an old Fordson tractor. It spans a metre between the uprights. You wouldn’t want it any shorter than that. On a trial run, the swinging block hit one of the uprights and really shook the whole structure. We ended up putting in eight-metre-long stays on each side of the trebuchet to make the whole thing more solid.”

Steel

Instead of buying expensive bolts to lock the tree trunks together, Dave drove 12 mm reinforcing steel through the wood and bent the ends over. The 13-metre throwing arm has a diameter of 300 mm at the counterweight end, and it tapers down to about 150 mm at the end where the projectiles are placed.

“We were basically working with what we had. The real challenge was seeing what worked without any serious planning,” he said.

Asked how he determined the height of the machine, Dave said it was basically the height of the trees. On the top of two main uprights, he left natural forks for the axle used as a fulcrum, which sits about four metres from the ground.

Getting the throwing arm up and mounted on the fulcrum was tricky but no real obstacle to a Taranaki farmer. They piled up big round hay bales to get the arm to the right height, three bales at one end and two at the other.

Dave then had a problem, as the trebuchet was constructed on the tanker track. The cows were calving, and the tanker needed access to the milking shed. He made and attached some wheels from big macrocarpa rings, making the machine look like something from world of Stone Age cartoon character Fred Flintstone. The machine was pulled into a paddock with a tractor.

Grunt

Pulling down the arm ready to fire the trebuchet takes a lot of grunt, as slaves in the old days knew. “We didn’t have enough slaves,” says the Taranaki farmer, “so we pull it down with the tractor each time.”

The trebuchet is launched by pulling a wooden lever (another Flintstone device) that has a pin driven into a wooden shaft. That releases the rope holding the arm down.

Another innovation is extending the throw of the trebuchet by attaching the projectile to a four-metre-long rope and placing it on a launching chute (a long piece of tin). The chute, about four metres long, sits under the throwing arm. The bigger the throwing arc the further the projectile travels and the rope adds another four metres to the throwing arm. When the throwing arm reaches a certain angle, a small loop on the end of the rope securing the projectile slips off a pin, and away the missile goes.

“The angle of the pin is crucial,” says Dave. “It has to release the projectile at just the right time. A lot of trial and error soon sorted that out.”

Firing time

At demo time, we all stood well back. Dave revved up the tractor and drove away to pull down the arm; there was a lot of power about to be unleashed. The strange thing about firing the trebuchet is that it’s totally silent—just a muted whoosh and a few creaks as the projectile takes off. It’s all quite impressive. The water container full of water exploded in a shower on hitting the ground –

they’ve gone through quite a few plastic containers, which left a crater where they landed. The arm and block swing for quite a while after launching. It was all quite eerie.

The boys agree the best firing so far was the couch, launched for a demonstration for TV’s Close Up programme. There’s something exciting about seeing a couch flying through the air. I don’t think any of us really do grow up. The boys said firing petrol-soaked flaming missiles at night was also a lot of fun.

Dave said the project has left him with an appreciation of the engineering skills of the medieval warrior who invented the machine.

Dave’s shed

Dave does actually have a shed. As well as being a bit of an inventor, he restores vintage tractors and farm machinery. He has a collection of old Caterpillar crawlers, stationary engines and an old Buick convertible awaiting restoration. He is on the Taranaki Machinery Trail, which runs alongside the big Taranaki Rhododendron Festival. The trail is something for the blokes to do while wives check out the gardens.

Also on the farm is an extraordinary Pelton wheel and generator that a previous owner of the farm installed in 1904 to power the milking shed and belt-drive the milking plant. At a time when many towns didn’t have electricity, the widow who ran the farm and a farm worker dug a 500-metre trench by hand to divert part of a stream to run the system. Dave has dug out and recovered the apparatus so it can be on display. But that’s another story.

He’s considering having a bloke’s day out over summers for fathers and sons, firing up the trebuchet and scattering the cows, which are getting concerned over the strange objects that are falling from the sky.

Throwing power

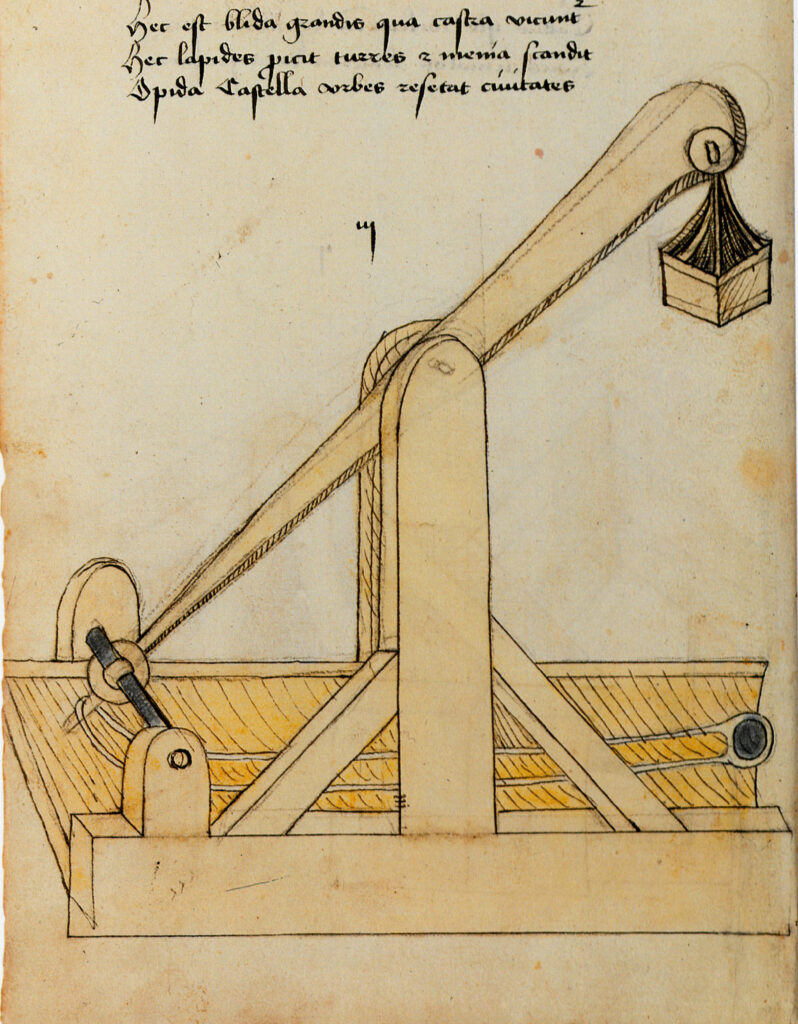

Trebuchet from Bellifortis, a 15th-century manual of military technology.

Man-powered trebuchets, or catapult-style siege engines, appeared as early as the 4th century BC in Greece and China. The counterweight refinement of this weapon became well-known in the late Middle Ages from the 12th century.

Trebuchets could be set up at a good distance from forts and castles, out of the reach of enemy arrows, so they were used in sieges and on battlegrounds to throw heavy projectiles (up to 140 kg) long distances. They were also used to hurl diseased corpses and even horses over the walls of besieged towns to infect the inhabitants, a medieval form of biological warfare.

The medieval machines took the ancient rock-throwing catapult a stage further with the clever use of physics. Wikipedia says hinged, counterweight trebuchets appeared in 13th-century China when the Mongols, after besieging two cities unsuccessfully for years, brought in Persian engineers to build the machines to reduce the cities to rubble, forcing the surrender of the garrison. Trebuchets were still effective after gunpowder and cannons were introduced but became obsolete in the 16th century.