Creating a model train harnesses the same skills as rebuilding a classic car

By Ray Cleaver

Photographs: Rob Tucker

They say variety is the spice of life. So it is in the shed.

For Taranaki mechanical design engineer Michael Wolfe this means working on projects as diverse as rebuilding a high- powered 1970 American muscle car through to intricate work creating a model of a classic Swiss 1960s train.

Michael re-builds and maintains full-size classic cars and in his spare time model railway construction keeps him busy.

“The skills needed are much the same,” said Michael. “It’s really all a matter of scale.”

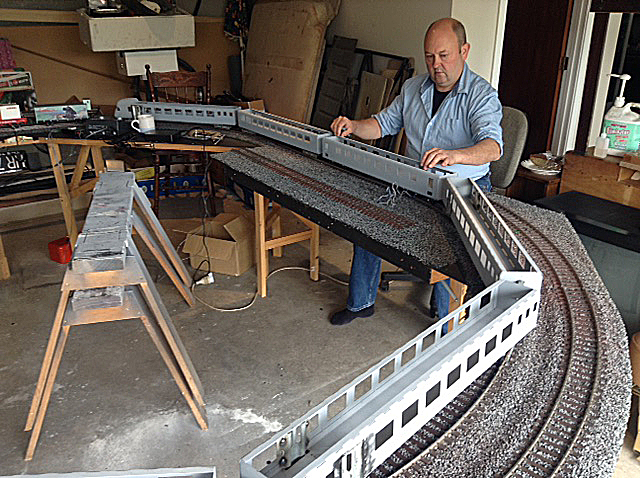

His hand-made creation of a replica of an iconic Swiss electric train, the RAe TEE II, is unique – probably the only one in the world. Panel construction, lathe work, welding, woodworking, and even creating parts with a 3D printer have all been part of the job.

In the world of model trains, this is a big one. Each of the six cars that make up the luxury train is about 800mm long. Michael started off with some plans, photographs of full-size trains, and books, all of which he used to create initial drawings.

The build

These were put onto a CAD file so the bodies could be cut out from 0.9mm thick electro-galv steel with a water-jet cutter. This is steel with a zinc coating. The steel was cut and folded, and then carefully spot welded with Michael’s UniMIG 160 welder.

“I had it on a real low setting as this is pretty thin steel,” he says. “It’s really the same as making a full-sized car body but all in miniature.”

Some very careful filing and finishing with a fine putty-coat filler was next. The roofs of the cars are made of wood. Michael used pine. He used the water-jet cutter to cut thin strips of aluminium that he carefully glued to each roof to make ribs.

Next up was a primer, then a top coat of automotive lacquer applied with the panel shop spray gun and an air brush for fine details.

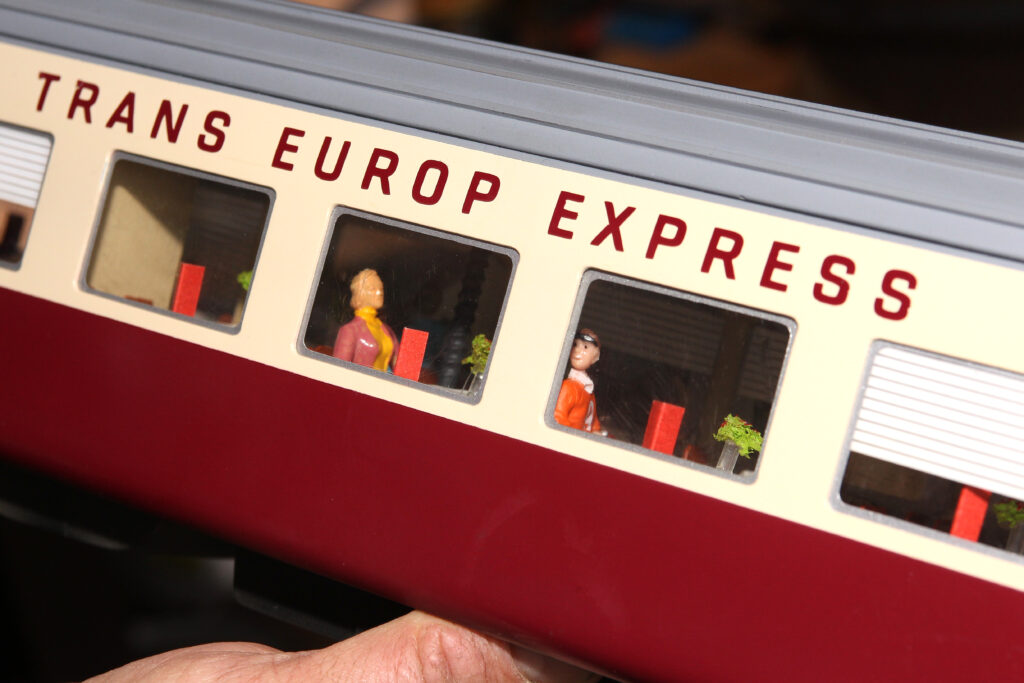

The metal parts for the bogies under the carriages Michael made from mild steel and the wheel units, with tiny ball bearings, came from America. Grant Hall of Vital Signs in New Plymouth made all the decals and sign writing using his computer. He also made little venetian blinds from white strips of film, and frames for around the windows. The window glass is made from plastic packaging. The detail is great – there’s even little menus on the tables of the dining car.

Finishing plastic pieces were made on Michael’s 3D printer. The figures in the train are made by Preisers of Germany, who specialise in making little people for models. There’s LED lights, front and rear, which change from red to white, depending on which direction the train is running.

The Trans-Europ-Express (TEE) was a premier train in its day, running through Switzerland and to Germany, Austria, and Italy. The train is a Gauge 1 model, built on a scale of 1:32. Gauge 1 is one of the biggest model train sizes. It needs a very big track and Michael has built six units for the train, a power car, and five carriages. The power car is in the middle of the train, which can move in either direction.

Detailed work

Time-wise he compares creating the model train with rebuilding a classic car.

“It probably took me about 300 hours to make the train. It’s very detailed work,” he says.

Michael has a big metal lathe for car restoration and a miniature Unimat model lathe for turning tiny pieces for the train. He showed The Shed the tiny insulators on the train roof, each one a few millimetres long, that were made on the model lathe. The power car has 16-volt AC motor units and a computer that drives other functions such as sound effects, including the humming of the motor, air brakes coming on, and announcements for stations.

Michael is an auto restorer looking after a collection of classic cars owned by Bryce Barnett (see The Shed, February/March 17). He has also featured with a mini caravan that matches his Mini Cooper car (The Shed, May/June 17) and his own two model railway layouts (The Shed, July/August 17).

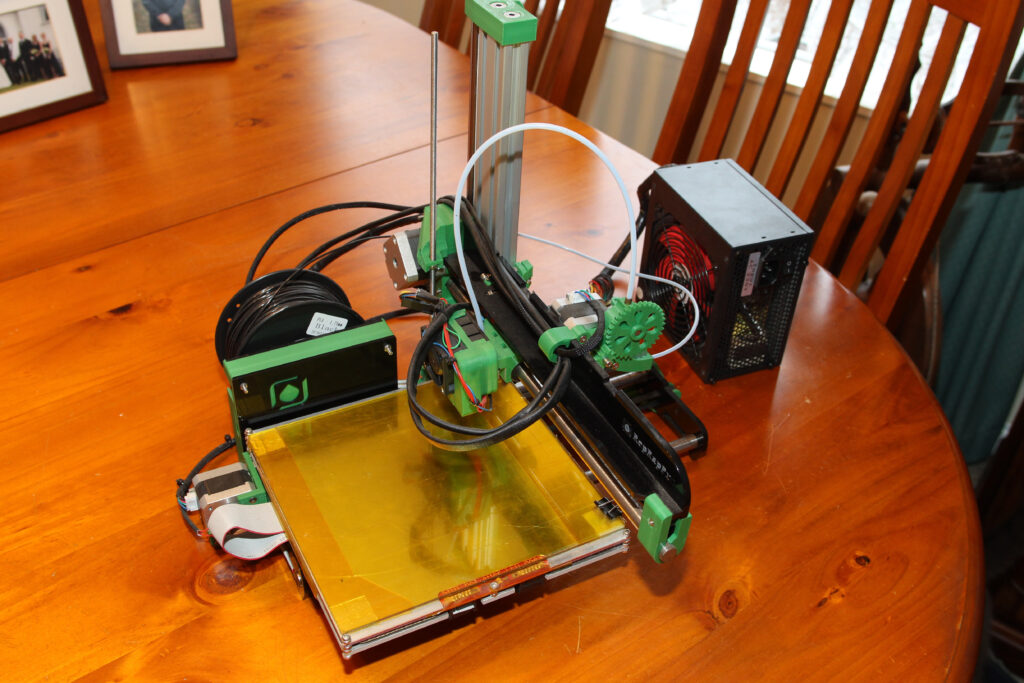

3D printer

Some of the finishing parts were made on a 3D printer. Michael’s son Nickolai is the computer expert and he and Michael made up windows, vents, and covers for the bogie wheel with the printer.

The printer looks like a simple affair, with a base panel and a nozzle, both of which move independently. A spool feeds the plastic filament into the printer and it is reduced to a 0.2mm fine strand which is squirted into the required shape. To make one of the bogie wheel covers for the train the printer took about 15 minutes.

“It’s a really great tool,” says Michael. “If you break or need any parts, you can just make them yourself.”

Scanning the plans

Michael created the model for Wellington train enthusiast Douglas Parker, who has a Gauge 1 layout. There are very few Gauge 1 tracks in New Zealand. Because of the size of the trains, these layouts take up a lot of space. Douglas scanned in the plans for the cars from books and scaled them up to 1:32 (Gauge 1) scale in height/width, but only to around 80percent of that in length.

“The coaches are shorter than scale-length, so they can more easily handle the tight radius curves on my model railway,” he explains. “The power bogies on the driving-trailer are from Aristo-Craft – their wheels were designed for the higher-profile rails of American Gauge-1 model railways, so a friend in the Märklin Club turned the wheel-flanges down for me so that they would run okay on Märklin Gauge-1 track.

“The wheels for the rest of the coaches are from Bachmann, with ball-bearings I purchased locally.”

The decoder is a LokSound XL decoder, from the German company ESU, mounted under the power car. The decoder controls the motors in the power bogies, controls the lighting in the coaches and headlights, and plays realistic sounds through the 78mm speaker also mounted under the power car.

“To get the sounds, I downloaded the ESU sound project for the RAe TEE II from their website and uploaded it into the decoder. It contains sounds from recordings of the real rail car, matched to the operating status of the train – acceleration, track-noise, and brake-squeal. Horn and station announcements play when prompted by commands from the controller,” he says.

An iconic machine

The Swiss Federal Railways built five of the RAe TEE II railcar sets in the 1960s.

They had four different pantographs which, in conjunction with their multi-voltage wiring, allowed them to operate under seven different European railways electrical systems. They all carried first-class passengers only as part of the TEE (Trans-Europe-Express) network. (The red-and-cream colour-scheme is the TEE livery.) They operated on routes from Paris, Brussels, Amsterdam, and Germany, through Switzerland and into Italy.

Once the TEE network stopped operating, in the late 1980s, they were repainted in a two-tone grey livery and reclassified as second-class Euro-City express trains (although they actually retained their first-class seating and facilities). The two-tone-grey livery earned them the nickname “Grey Mouse” in Switzerland.

They were retired from service in 1999 however one has been preserved by SBB-Historic. Restored and repainted in its original livery, it is based at Erstfeld in Switzerland, and runs for historic events.

Michael and Douglas’ model has the same number as the preserved railcar.