Junk is made into futuristic fabrications by a talented man of all trades

By Sue Allison

Photographs: Juliet Nicholas

A sci-fi artist working from a backyard shed in Central Otago is turning stuff no one wants into things that are sought after across the globe.

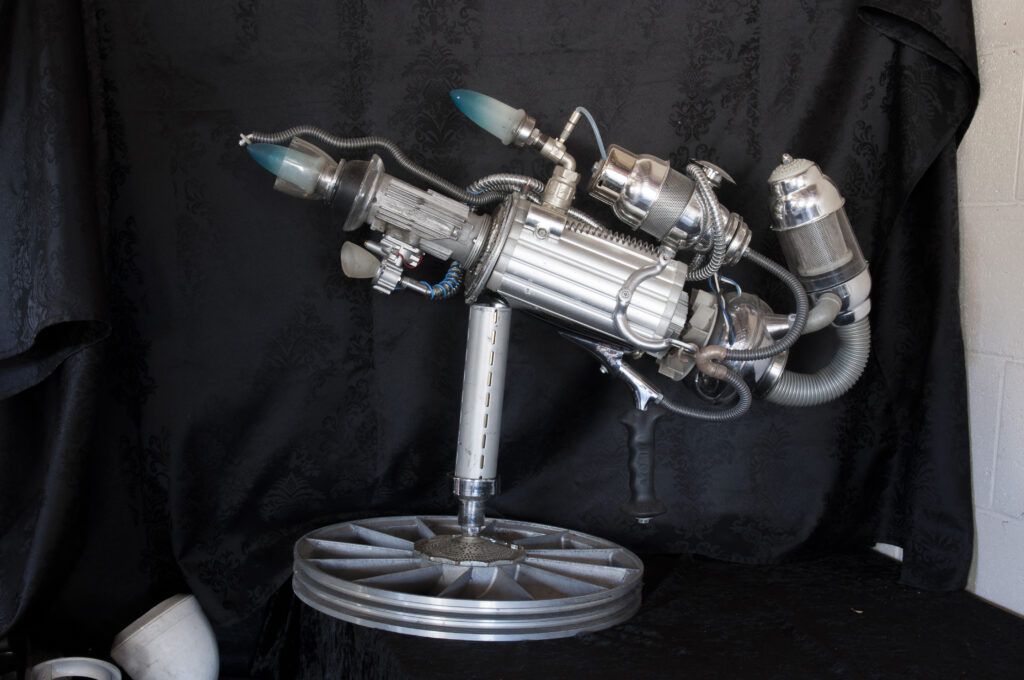

Sean Boyd uses anything that takes his fancy, from light fittings and plumbing parts to typewriters and old vacuum cleaners, to make futuristic fabrications which include ray guns, life-sized robots, jetpacks and other cosmic curiosities.

“The satisfaction is in finding parts, imagining outcomes and working out how they can fit together,” says Sean, who gets most of his raw materials from the local recycling centre, Central Otago WasteBusters. “I fill the back of the car for about $35. I think I’ve got more waste here than the waste station,” he says, looking round at the piles of paraphernalia in his humble garage in Clyde.

Are these real?

Sean’s creations, many of which look as if they’ve been unearthed in a Raiders of the Lost Ark archaeological dig, are designed to look and feel real, from his ray guns to an apparently steam-powered walking stick complete with moving pistons. “I like to create pieces that make the onlooker question if they’re real, before investigating further to discover they are created from everyday items,” he says. “I know I’ve done my job when I see people looking from 30 metres away thinking ‘What the hell is that?!”

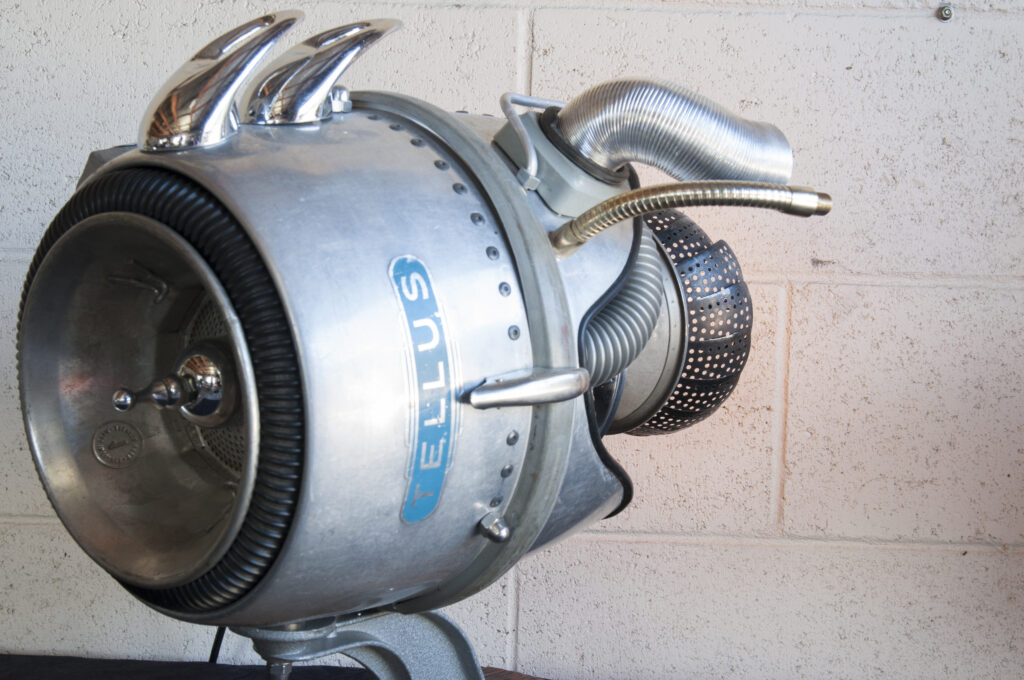

While no junk is without possibilities, Sean has favourite materials for his sci-fi sculptures. He loves the shape of the classic Tellus vacuum cleaner and says the plain casings of defunct Zip and Rinnai water heaters often cover quirky internal workings and sought-after raw materials like copper tubing. Cogs and gauges are hard to come by since the steampunk movement gained popularity, but Sean recently scored a windfall of nine brass gauges from a Roxburgh hydro-electric dam refit. “They were going to throw them out, but the electrician said, ‘I know someone who’ll want them.”

Parts harmony

He likes to keep the integrity of the original components while camouflaging them by their placement. “It sometimes feels like cheating because someone has already done the design work, but the art is in getting bits that look right with each other,” says Sean, whose eyesight is live-wired to his imagination. A double-headed ceramic insulator is an owl’s head; a box of cupboard hinges a scorpion; a set of light fittings that were “smirking at me” became a family of happy aliens; an old diesel burner’s fate was sealed because of its uncanny resemblance to Kenny on the South Park TV series.

He holds up the expansion chamber from a two-stroke motorcycle. “Isn’t that beautiful? I’m going to make it into a hummingbird,” he says. It won’t be an ordinary bird but some whimsical galactic creature that likely lights up.

Lamps are among his best sellers. “Some people are happy with things they can just look at while others want things that do something,” says Sean, who does the wiring himself, then gets it checked and ticketed by an electrician.

Useless inventions

Others seek the spectacularly impractical. Sean, who has exhibited at the World Of Wearable Art (WOW) in Wellington, is currently devising a series of patently pointless pieces for an exhibition of Useless Inventions at Wanaka Puzzling World. So far, he has hatched up a hamster-driven Singer sewing machine, a cooking pot with an internal handle and an utterly useless cutlery set with rope handles.

Apart from a bit of showmanship for the photo shoot, Sean says he does very little welding. “I lay all the pieces out like a big jigsaw then usually bolt or screw them together.” Aside from spanners and screwdrivers, his most-used tools are a second-hand drill press salvaged from a deceased estate, a Ryobi bench grinder, and a hacksaw.

Dremel tools also come in handy for inscribing alien hieroglyphics on metal surfaces. His shed is packed with potential-laden junk sorted into such categories as brass and copper, stainless steel and aluminium, plumbing parts, and light fittings. He tries to keep it tidy but not overly organised as he figures fossicking keeps his mental inventory up to date.

Going with the flow

As far as construction goes, Sean doesn’t follow plans and has neither rules nor boundaries. “I don’t sketch anything. I pick things up and look at them and think, ‘That’s how you normally look at it, so what is it like that?’ Then I start grabbing other things that fit with it and start assembling. I tend to be quite manic when I’m in the mood,” he says. “As long as I’m having fun, it will be a good result.”

Sean sells his works through an online mailing list, with most pieces selling within an hour or two of being offered. His international market has grown as steadily as the stream of tourists pedalling through town on the Otago Central Rail Trail, and business fair rocketed when he took his wares to the Queenstown market. His biggest market is Europe, but he also has a solid fan base in America. Of the 125 major pieces he has made in the past five years, each worth around $2000, only 10 have remained in New Zealand.

Meet Roger

One is ROGER (Recycled Object Gathering Electronic Robot), a 1.5 m-high, 1970s-style automaton who stands in reception at The Mind Lab science discovery centre in Auckland. A German visitor was so impressed that he ordered one for himself, but requested a “menacing earth invader, not a comical butler”.

Sean fitted arched taps to form malevolent eyebrows on its rice-cooker head and incorporated an old microwave, vacuum cleaner hose and trailer lights into the rest of the body. That client has bought 32 pieces and flown Sean over to Germany to help set them up in his mansion, where he has a collection of more than 200 motorcycles and a Swiss military helicopter suspended from the ceiling. While over there, he lent Sean a motorbike and went touring with him for a couple of weeks. “All from making stuff out of junk,” Sean muses.

He takes on a few commissions, but insists there is no obligation to buy as they will be the products of his own imagination and interpretation. When the owner of a tattoo studio in Germany with a warped sense of humour wanted a device to scare nervous customers, Sean obliged with a jackhammer-sized contraption complete with syringes full of coloured dyes leading to a drill tip.

No two creations are the same. “You can have all the money in the world but the only difference between your Lamborghini and your neighbour’s is the colour of the trim,” he says. “With these, you’ve got the only one in the entire galaxy.”

This article first appeared in The Shed magazine, issue 78, in 2018.

To view more of Sean’s creations, check out his current website: https://www.octalien.com

Space oddities

Cosmic characters to make their way out of Sean’s shed include the Cyborg Stellanating Receivanator, Galacton Warper, Plasma Distillinator, and Maximum Regalis. “I come up with crazy names and used to write a story for each one,” he says. At first, his yarns revolved around wiping out races of aliens, but with the rise of ISIS and global strife,e he changed tack. “I now market myself as a failed intergalactic gunsmith who made these amazing contraptions to help people, but they ended up hindering people, so they have been decommissioned and are just ornaments.”

His Fistillator 500, for example: This submariner ray gun was designed for the elite forces of Atlantis. They requested a design that was light, easily manoeuvrable, powerful, and durable. I managed to make it all of these things, except I forgot to make it waterproof. Needless to say, they did not purchase any so this is the only underwater leaky ray gun in existence.

“I just haven’t grown up,” says the Peter Pan of Never-say-Never Land. “I see things through a nine-year-old’s eyes.”

A man of many trades

Sean started out bending steel in a factory after leaving school aged 15. “You would get a million rods and put a 90-degree bend in them, turn them over and put a 90-degree bend on the other side. I did that for a while, then I did plastic injection molding. Then I did welding, and then I was an oyster farmer.”

Born in England, he came to New Zealand as a baby, but has moved backwards and forwards between the hemispheres, along the way working as security for the Chelsea Football Club, and as a takeaway cook. “I never knew where I fitted so I just kind of did a bit of everything.”

Sean had a lightbulb moment when someone explained to him how an engine worked. “I really took it on board and went back to school and got my mechanic’s apprenticeship.”

He went on to sell cars, clean cars, work as a service advisor and manage a workshop before joining the police force. He spent 10 years in the force, including five years as a constable in Alexandra, followed by a stint as a probation officer, which reinforced his belief that a creative outlet is essential for everyone and can steer people away from offending.

“I can’t draw to save myself, so I never thought I was artistic or creative,” says Sean. Then one day in 2012, the self-confessed hoarder was fiddling in his shed and came out with a ray gun made from an oil lamp, an old electric drill, a drawer handle and a corkscrew. Impressed with his handiwork, he put it up for auction on Trade Me. “It had over 10,000 views and sold for $300, and business skyrocketed from there.”

Sean, who has lived in Clyde for the past 10 years where he shares the care of his 12-year-old son and 9-year-old daughter, took a break from science fiction a few years ago to work on a more practical invention – a hi-tech, carbon-fibre snow sled that he saw as an alternative to snowboarding and skiing.

His Snolo Sleds business won third prize in the ANZ Flying Start competition and looked set to take off internationally, “but didn’t fly in the end” as other grown-ups were slow to catch on. Sean is now pretty much a full-time junk artist with a bit of window-cleaning thrown in “to get me out and talking to people”.

Through children’s eyes

Sean is a great believer in the power of the imagination and the importance of nurturing the inherent creativity of children.

School groups regularly visit his shed. “It’s like Aladdin’s cave to them. I roll up the garage door, and their eyes light up,” he says. “I tell them art is whatever they want it to be. It’s not about what other people think of it. It can be anything. It can be a toothpick sitting on a green background in the Guggenheim.”

Imagination is something that is lost, not learned. “Kids have got it. If you hold up an iron and say, ‘What does this look like?’ then turn it over and say, ‘Now what does it look like?’ adults go, ‘It’s an iron, it’s an iron, it’s an iron’. Kids go ‘It’s a boat, it’s a submarine, it’s a sail’.”

Sean left school as soon as he could and thought he was stupid. “The first memory of school was the teacher asking me what the time was. I didn’t have a clue. She said, ‘What number is the big hand on?’ and I looked at them and thought, ‘They’re both big but one is short and fat and the other is tall and thin’. Under pressure, I thought, ‘You say people are big if they are fat, so I’ll go with the fat one.’ Everyone laughed at me and I thought, ‘How come everyone else knows this but I don’t?’ Looking back, I saw them as being the same volume but didn’t recognise that then.”