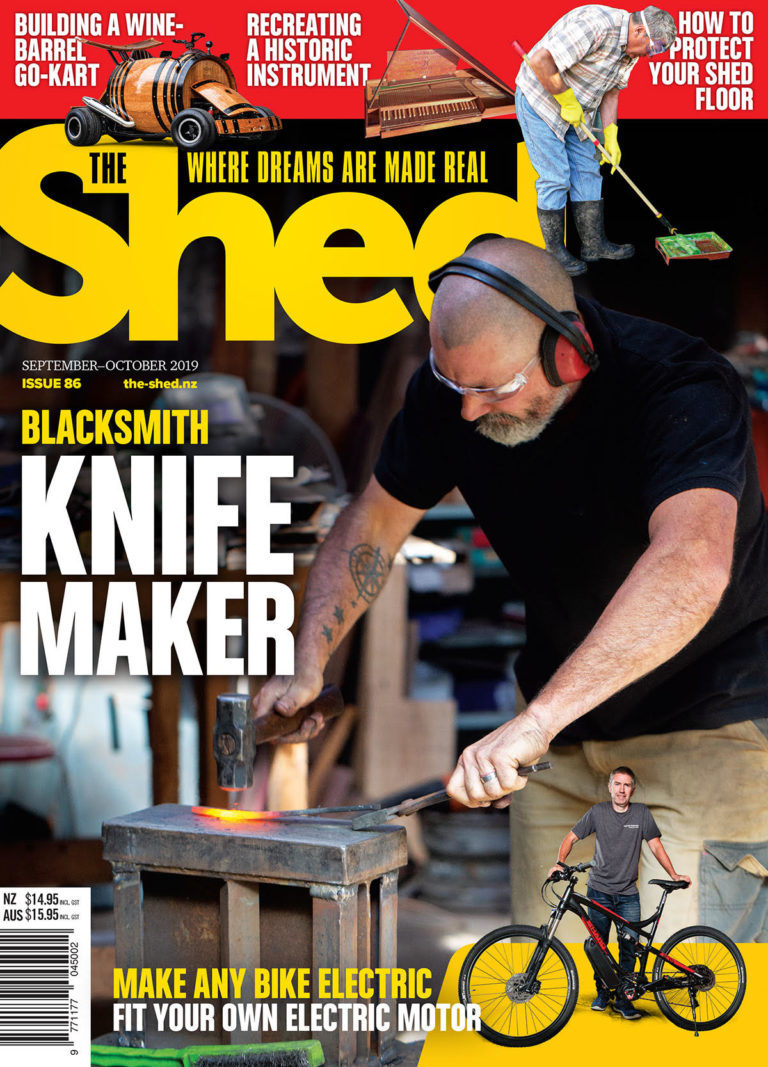

A blacksmith is a master of the ancient art of heat and hammer

By Sue Allison, Photographs: Juliet Nicholas

A yellow sign indicates an historic site ahead and soon an old corrugated shed with “Blacksmith 1889” emblazoned on its side comes into view. Not so unusual, but a driver might do a double-take when he spots the glow of the ancient forge and hears the ring of metal on metal as he passes. While the smithy in Teddington, on the road from Lyttelton to Port Levy on Banks Peninsula, is a relic from a bygone age, the man at work is a real live 21st-century blacksmith.

“This is what I’ve done all my life,” says Les Schenkel, who can be found at work down at the blacksmith shop on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. Horses, however, are not among his customers. Les, who spent his working life in Lyttelton as a blacksmith in the maritime industry, shied away from shoeing horses early in his career. “When I was doing my apprenticeship there was an old bloke who was all bent over. I asked ‘What happened to you, Norm?’ and he said, ‘I got kicked by a Clydesdale’.”

Les uses the forge to make everything from gates to trivets, anchors to pizza knives, and is Mr Fix-it in between. He is in the process of restoring an old copper for storing firewood, while a curious bike rack is leaning against a bench. “I’ve made that for a fellow who wants to tow his wheelie-bins up a long drive,” he says. Other one-off orders include a clapper for a cowbell for a goat and steel batons for a potato-picking conveyor for Maori gardens being established on the peninsula. He is also making a decorative gate for Ohinetahi Homestead, renowned for its garden, in Governors Bay.

Perfect spot

Les has been forging his wares in the restored building since it opened two years ago, making the smithy, which is leased by the Governors Bay Heritage Trust, one of the few operating blacksmith forges in New Zealand. Positioned at the junction of Gebbies Pass, with the Teddington (now Wheatsheaf) Hotel across the road, it was a perfect spot for a blacksmith to ply his trade in the 1880s. The hotel was equipped with stables and grazing paddocks, enabling farmers driving stock over to the Christchurch sales to take a break and see to their horses.

But as motor vehicles replaced horses on the farms and roads, the district couldn’t sustain a full-time blacksmith. For a while, the forge was manned by a visiting blacksmith, then it was used by Blatchford’s contracting business before being abandoned to the elements.

In 2015, local resident David Bundy spear-headed a project to restore the old smithy, which had completely collapsed. The building was rebuilt 1.2m above the original floor on new wooden piles. The roof was repaired with period iron and local recycled timber from the same era was used to rebuild the walls.

Authentic artefacts

The forge, quenching trough and some equipment were still intact, and the rest was re-fitted with authentic artefacts from the district. This includes a set of double-acting leather bellows from Robinsons Bay made by the English automobile maker, Alldays & Onions, which is operated using a wooden shaft fitted with a cow-horn handle. “They used cow horn on the end because it’s greasy, even after all these years, so when you’re pumping it you never get blisters,” says Les.

Okains Bay Maori and Colonial Museum have loaned them the anvil, while the swage block came from Luneys Construction. (Swage blocks are anvil-like dies with an array of templates forged into them, making them useful for forming a range of shapes.)

The watering trough by the road is original as is a lot of the horse tack inside. Old accounts show that draught-horses with names like Ada, Tommy, Maggie, and Duke were regular customers.

Les often starts his working day by grabbing a few handfuls of leaves from the old cabbage tree outside. “They make the best fire-starters,” he says. Once lit, the coal-fired forge is mechanically operated with air coming into the centre of the fire through a twier (mouthpiece) at the end of a pipe encased with water for safety. Les only uses the bellows if the fire is “a bit lazy”. Bituminous coal is best as it reduces to coke which burns hot and cleanly.

“It’s hot work,” says Les who, even on the hottest summer day puts on a woollen jersey when he has finished at the forge. Humans, like forged metal, should cool down slowly, he maintains.

Family ties

Les’s yard is full of old iron and steel. “I’m always after steel,” he says. “I go through a lot and it’s hard to come by and expensive to buy.” People drop stuff off, and he has picked up a few bargains in post-quake Christchurch. “I’ve got quite a few rivets from demolished old buildings. They’re about $1 a kilo at the knacker’s yard. It’s all about recycling.”

Alongside the smithy is a small outbuilding which Les is turning into his own museum of historic curios, while out the back smoke is rising from an old railway carriage. This is his smoko shed and daytime home for his two Australian kelpies, aptly named Digger and Anzac. A mobile phone sitting on the ledge is his only, and reluctant, concession to the modern world.

While Les Schenkel is no ghost of the past, those of his ancestors might well be lurking in the smoky shadows. His family has been living on the peninsula since before the blacksmith shop was built and he has a poignant reminder sitting alongside the smithy. He points to a long iron rod lying in the grass. “I got that from St Cuthbert’s Church in Governors Bay when it was being demolished. That’s the rod that was above the altar. My great-great-grandfather, Edward Morey, was the stonemason who put it there in 1862.”

Hammering spears

Spears are an example of drawing out metal, with Les stretching a 50mm rectangle of steel to an 80mm taper by hammering the hot metal to a point.

Les heats the steel to white-hot, or 1500˚C, then hammers it on his anvil with various pein hammers in his fuller set. A “fuller” is a tool with a round or parabolic “nose” that is driven into the hot metal. His hammers range from lightweight peins for finishing off to a 28lb (12.7kg)S sledgehammer.

Les works quickly, changing hammers all the time and returning the spearhead to the fire as the glowing metal cools and dulls. It’s a rhythmic fire dance – heat and hammer, heat and hammer, with sparks of fiery scale flying with each beat. “That’s the most dangerous metal,” he says of the flaky surface residue. “It tends to stick to your skin.”

He dunks the handle in the quenching trough occasionally to cool it – but never the end he is working on. Ferrous metals such as steel must be cooled slowly to anneal. If plunged into cold water they can snap as the carbon crystallizes, or at least create a flaw.

Once the spear has reached the required length (marked on his anvil with engineers’ chalk), Les hammers along the neck to make an indentation, which he later cuts through with a hacksaw. “If I was mass-producing them I would make a form, but I just do these by eye.”

He attaches the spearhead to a steel rod using his electric ARC welder. Once that is done, he puts the whole piece back in the fire for normalising. “Every ding represents a flaw,” says Les. To get rid of the flaws, which create stress, you need to heat it up to 930˚C, above its recrystallizing temperature. It must then be cooled slowly to allow the metal to anneal.

Scrolls and hooks

The carbon in steel turns to liquid at 900˚C, allowing it to bend, Les explains. To make decorative scrolls and hooks, he heats the metal then pulls it around a jig or bending dog. Les makes a lot of his own jigs and tools.

To make a scroll, he holds the 6mm steel rod with tongs, first hammering the hot metal to draw it out to a tapered point. When bending, it’s important to keep the rod evenly heated so it doesn’t curl irregularly. Les heats the tapered rod, quickly fits it into the curling jig and walks it around until the shape is formed. For a double-ended scroll, he repeats the process on the other end and finishes by hammering out any imperfections.

Making hooks is a similar process, except the malleable metal is pulled around the prongs of a bending dog.

The blacksmith’s trade

A smith is someone who works with metal. A blacksmith works with iron and steel. A farrier is a blacksmith who shoes horses.

Blacksmiths create objects from wrought iron or steel by heating it in a forge until it becomes soft enough to shape with hand tools, such as a hammer, anvil, and chisel. Unlike metal machinists, they don’t remove material. Instead, they hammer it into shape, manipulating the form while it is hot and malleable.

The first blacksmiths were Hittites, who started make tools with iron around 1500BC. The ways tools are made by blacksmiths has changed very little since then. They involve these basic processes, or combinations of them:

Drawing is hammering on the sides of a piece of hot iron to make it longer and thinner. This can be achieved using an array of tools and methods but, typically, the hot metal is hammered either on the edge or flat face of the anvil using the cross pein of a hammer.

If tapered in two dimensions, a point results. (To finish a blade, the cooled steel is sharpened with a grinder after the metal is cool.)

A quicker method for drawing is to use a fuller, or the round pein of the two-headed hammer. Fullering consists of hammering a series of indentations across the long section of the piece being drawn, resulting in a series of waves along the top. The smith then uses the flat face to hammer the ridges down. This forces the metal to grow in length (and width if left unchecked) much faster than just hammering with the flat face.

Bending is hammering a piece of hot iron to make it curve or form an angle. Bending can be done by hammering the metal over the horn of the anvil or by inserting a bending fork into the Hardy Hole (square hole in the top of the anvil) and bending the pliable hot metal between the tines.

Upsetting is hammering on the end of a piece of hot iron to make it shorter and fatter. The rod is hammered as if driving in a nail, thereby widening the hot part and shortening the rod.