Moving to a retirement village means model engines are now the go

Photographs: Steve King

Something that many shed owners must face at some time is how to maintain their hobby if they

have to downsize their property. Owen White is one person who has successfully achieved this by

not only downsizing the house but downsizing the hobby. Instead of restoring old internal

combustion engines he now makes scale models of them.

In the 1960s, Owen got hold of a 1930s 9 hp Briggs and Stratton stationary engine to restore and

was bitten by the vintage engine bug. It sparked a 50-year passion for old combustion engines, and

for repairing, restoring and running them at vintage engine shows. Owen joined the Vintage Engine

Restorers Club in 1985 after attending their third meeting and remains an active member.

He has amassed a library of rare books on vintage engines and has contributed some of his

knowledge to a book written by Richard Robinson entitled

Stationary Engines Made in New Zealand.

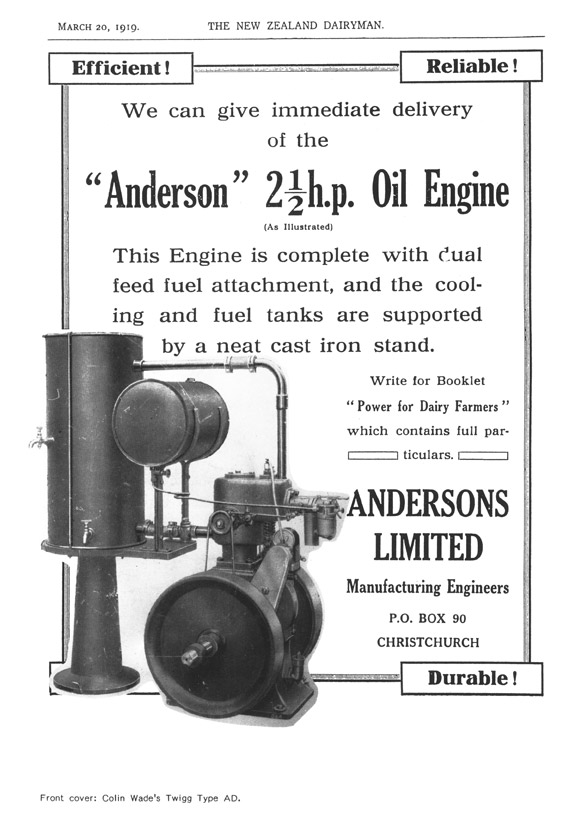

He says “There have been more than 40 manufacturers and 60 models of

engines made in New Zealand. I’ve owned a 1921 and 1963 Anderson, a 1917 Greenslade and 1942

Boothmac.” A model of his 2 ½ hp 1921 Anderson sits on a bookcase in the lounge.

Rusty bits

Many of the engines he has rebuilt often started as boxes of anonymous rusty bits. Sourcing or

manufacturing missing parts and researching the history of the model and manufacturer was all part

of the journey. He has photographs of an old Petter diesel engine that was burnt out in a fire then

left for five years by the seaside. When he pulled it apart he found the heat of the fire had melted

the piston. Fortunately, one of his contacts managed to find him a spare one.

At one time he had a collection of 43 engines and a purpose-built, well-equipped workshop to keep

them in. However seven years ago at the age of 80, Owen with his wife Margaret found that

maintaining their large property was getting too much. They decided to shift to a retirement village

where they could have access to care if needed. After looking around they found a house in a

retirement village in the eastern Auckland suburb of Pakuranga. Importantly, it had a large single

garage.

The major problem with moving was what to do with a lifetime’s collection of engines, spares and

workshop equipment. Slimming down the contents of his shed to fit the new reduced space was no

easy task. “I must have given away trailer loads of stuff” Owen says. Engines were sold off to

collectors around the country apart from a couple of small ones that sneaked their way into the new

garage.

Saying goodbye to the engines that he had put so much time into was hard. But he made sure they

went to good homes where they will be cared for. He keeps in contact with many of the owners and

still sees some of them at the meetings he goes to.

Miniature replicas

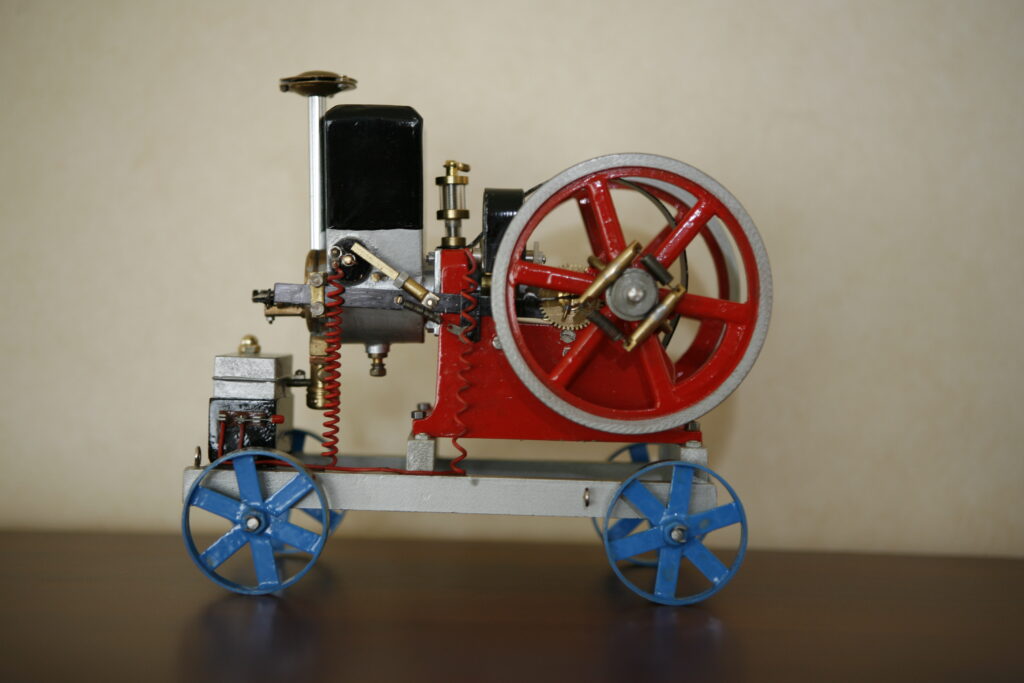

With the scaling-down of his shed, it made sense to scale down the engines too and Owen began

building miniature replicas of both the engines he owned and ones he would have like to have

owned.

Owen has always built things; his life is full of designs, inventions and projects he has created since

he was a boy. He remembers as a child, being fascinated by the milking machine motor on his

father’s farm and his great uncle building a water-powered grit mill for turning oyster shells into

poultry supplement. Tragically, his father was killed in a hunting accident when Owen was just

seven.

Starting his career as a telephone technician back in the early 1940s when exchanges were full of

noisy, high-maintenance electro-mechanical switch gear, Owen learned many skills that proved

useful both his hobbies and career. During World War II he worked for a company making

equipment for the army and with supplies of parts often unavailable, they had to improvise. One

project involved building generator sets powered by lawnmower engines to charge aircraft batteries.

The skill of adapting and making things from scratch has lasted a lifetime.

Plenty of projects over the years

Owen is full of stories about things he has made such as a solar-powered hot-water shower for his

bach; it was fabricated from galvanised steel sheets used for packing transformers.

“I made up a big shallow tray, stuck it onto the toilet roof, filled it with about 3 inches (75 mm) of

water and covered it with black polythene. It was a beauty,” he laughs, “it got so hot. Margaret was

the first one in and boy, did she jump. You could get six showers a day with one fill.”

He made a cam-operated SOS signal light for his boat using a small electric motor to open and

close a contact to turn the light on and off in the correct sequence. He even made a cake-mixer for

his wife from an electric motor that was originally used to winch bombs into aircraft. “I got hold of

a lot of those motors just after the war. They were beautifully made, incredibly powerful and geared

right down. I used them for all sorts of things. They were that strong I even used one to winch my

12 ft 6 (3.8 metre) boat onto its trailer.”

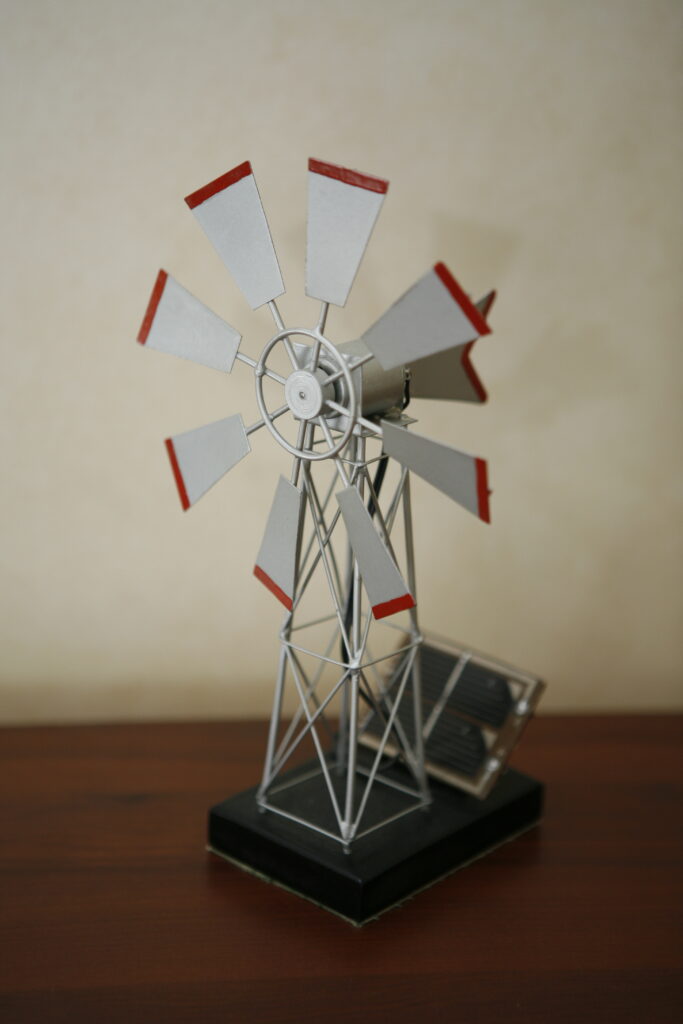

He has also experimented with wind power, building several windmills to generate his own power

starting with a 10 ft (three-metre) high one with a 6 ft-diameter (1.8 metre) blade scavenged from a

1946 wind generator. Each model stepped up in size, sophistication and power culminating with an

8 ft (2.5 metre) blade windmill running a 24 volt 30 amp system that powered the workshop he had

built out the back of the family home in Pakuranga.

Their new home had a small model windmill in the back garden for a while but this has now been

replaced by a home-made anemometer that measures wind speed and direction and displays this on

a converted clock in the kitchen.

Windmills

Engines and windmills are not the only sort of model that he has built. The entranceway of Owen

and Margaret White’s house is dominated by a 5 ft (1.5 metre) highly detailed model of the Castle

Point lighthouse Owen built. He had visited the real working lighthouse on the Wairarapa coast and

tells of when, as a child, he was there and the area was struck by a large earthquake. The rotating

light used a 550 kg pool of mercury as a bearing and some of this spilled onto the lighthouse floor.

He helped to clean up the mercury, using envelopes to scoop up the fluid into a chamber pot.

Owen built the model from photographs, using galvanised steel from transformer packing boxes for

the tower and a plastic storage container for the lens. Getting the local sheetmetal-worker to roll the

main tower was a bit dear so Owen decided to do this work himself.

“I just rolled the steel sheet up on the back lawn and when I had the right diameter and taper I

strapped it up.” He adds, “To true up the ends, I rested it between the legs of an upside-down saw-

horse and rotated it while Margaret held a pencil to mark where to trim.”

All the model lighthouse details such as the railings and the aerials have been made by hand. Much

of Owen’s enjoyment comes from overcoming design challenges and making things from the

unexpected, rather than buying readymade items off the shelf.

Models

Models are built from scratch using line drawings or photographs and are scaled down to his own

formula, not by a specific ratio. And this formula? Owen says “I scale the engine models to the size

of flywheel I can make. I go to my local hydraulic pipe-supplier, see what diameter will best suit

my project and get a ½-inch (13 mm) or so wide piece that I can machine up in my lathe. I then take

my flywheel to the local photocopy shop and ask them to copy and scale the drawings I have to fit

the flywheel.” Owen has contacts who help him with machining larger parts, casting components

and sourcing parts but wherever he can he makes things himself.

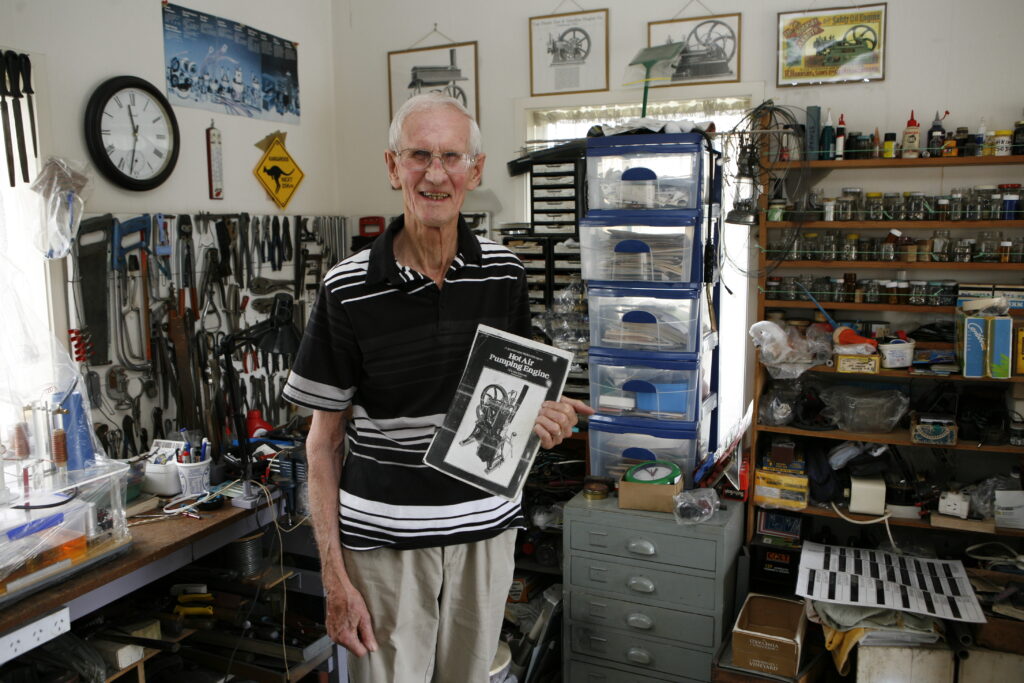

When you enter Owen’s garage, it does not seem crowded or cluttered despite the amount of

equipment it contains. There is even room for their car. The walls are lined with cabinets and

shelves neatly laid out with rows of small glass jars filled with nuts, bolts, washers, screws and

other bits and pieces. A shadow board on the back wall has tools fitted to every available inch like

an industrial jigsaw puzzle.

A full-size 1910 1½ hp Jumbo Line engine lurks under a bench; a petrol-powered Maytag washing

machine motor complete with kick-start sits under a protective sheet. A working model of an 1886

Rider Ericsson hot-air engine sits on a shelf. The New Zealand Formula One racing car champion

Denny Hulme owned a full-sized version of this engine. The model comprises 176 parts; Owen cast

seven of the main components using a friend’s model as a pattern and made the remaining parts

himself.

Current project

Next to the Rider Ericsson engine is Owen’s current project, an 1867 Otto Langen atmospheric

engine which uses a rack and pinion to drive the flywheel. Owen explains he will use an electro-

magnet to drive the rack rather than using heat like the original. “It’s almost finished but I need to

modify the ratchet I’ve made to get it to work properly.” Another project under way is a small Tesla

generator that just requires a bit of final sorting before the sparks really fly.

A Myford lathe with a full range of change gears and accessories sits up against the wall next to his

workbench. It is customised with a milling attachment that is bolted onto the back of the bed.

Neatly tucked beside the lathe is a drill press.

Drill press

The drill press has its own story. “I was given just the head and built the rest of the drill around it. I

had to rebuild the rack and made the table from a printer’s mould. The table is attached to the

column with a pipe clamp.” He adds “The motor came from a dairy farm where it had been filled

with milk and was being thrown out. I cleaned it up and got it going about 60 years ago and it’s

drilled thousands of holes since.”

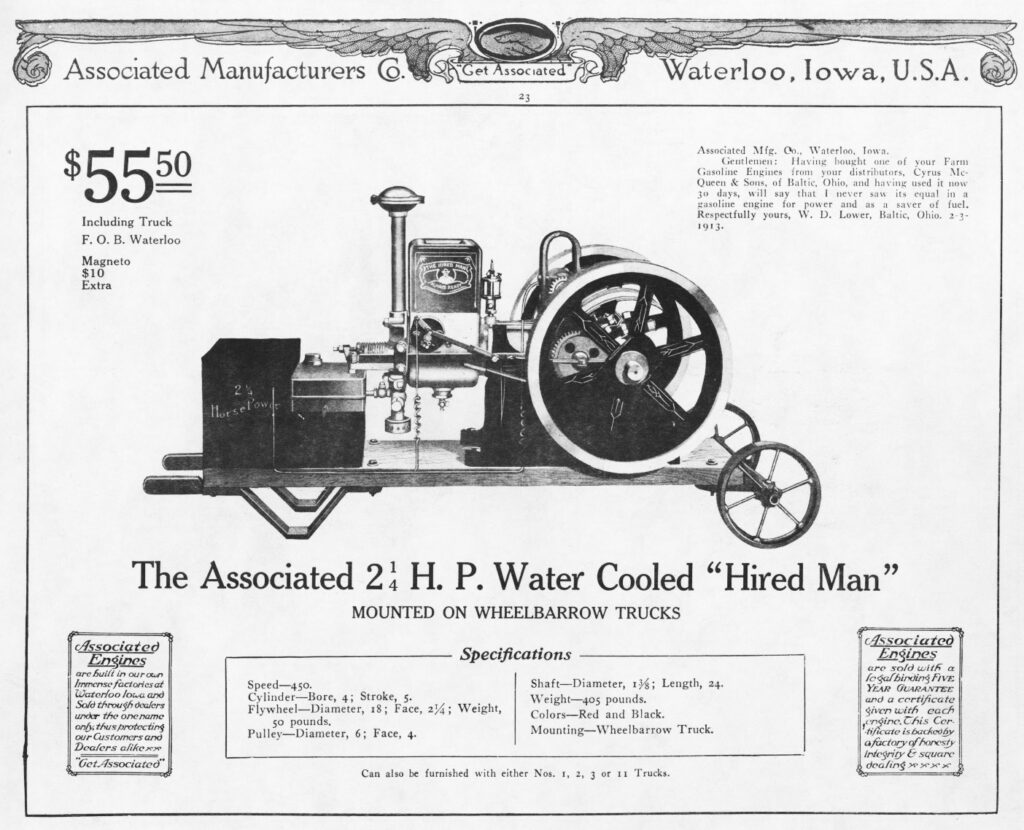

Shelves in the lounge, house several of Owen’s models including a 1921 Anderson 2½ hp engine, a

1912 Hired Man 2¼ hp engine plus two solar-powered windmills, a traditional Dutch-style

windmill and a waterwheel.

Owen is very hospitable and filled with stories and adventures about his life and work. His

enthusiasm for making and restoring things is still strong and his eyes light up when he talks about

his projects past, present and future. He and Margaret have been married for 60 years. Margaret has

her own interests so she does not mind the hours that Owen spends in his workshop.

The move to the retirement village has been good for them with plenty of company and activities to

get involved with. Owen has sometimes put on displays of his models for the residents at the

community hall. “When I first moved in I put a notice on the board asking if anyone was interested

in old engines and I got four chaps who came round. Unfortunately, they have all passed on since.”

He adds, “There are a lot of new residents here now so I might try putting up another notice.”

In the meantime, he has plenty of projects to get on with in his scale-model shed.

Kiwi “enginuity”

Defining a New Zealand engine was tricky for author Richard Robinson. In Stationary Engines

Made in New Zealand about mainly farm and marine internal combustion engines, he writes “To

document only those engines made in New Zealand has been impossible in some cases.

Manufacturers in New Zealand have been quite happy to import an engine, strip it down and use the

parts as patterns for their own forging. Some minor changes might have been made to suit

requirements but there was no guilt over breach of patents.” Robinson mentions Picton/Nelson

fishermen knocking up a boat engine when they needed one if they could not buy one and “no

doubt this has gone on around the whole country in backyards and country town workshops.”

Among the name brands is a Kapai engine by Auckland engineers Arthur & Dormer. It was

installed in a 50 ft (15 metre) canoe used between Ngaruawahia and Hamilton and the owners

“expressed great satisfaction with performance” when it reached 10 mph (16 km/hr) on a trial trip,

according to a report in NZ Yachtsman in 1910.