A 3.6 metre aluminium runabout in a couple of weekends

By Rebecca Hayter

PHOTOGRAPHS:

JIM PAULING/GERALD SHACKLOCK

The aluminium runabout – better known as the tinnie – is the quintessential Kiwi bach boat. Most arrive in the backyard direct from the showroom or the For Sale pages, but Auckland boat designer Jim Pauling has created a new way of getting a tinnie: building it by kitset.

https://www.jimpauling-yachtdesign.com/diyno-kitset-boats.html#/

He has several sizes in his range. One of them. the baby, is the DIYNO 361, at 3.6 metres long. Thanks to improved technology and lower prices for power tools generally, it is much easier for the home handyman to pick up a welder, have a few practice runs on some scrap aluminium, or do a course at night school, and build his own kitset, 12-foot tinnie.

Weekend building

Pauling is a diehard fan of aluminium as a building material. Thanks to CNC (computer numerically controlled) cutters, it can be accurately cut to shape for sale as a kitset, which saves labour and vastly improves the result. The tools required are inexpensive and found in most home workshops. Unlike timber, aluminium requires no gluing, fibre-glassing, sealing, fairing, or painting so, once the aluminium boat is finished, it’s finished, making for a much quicker build-time. Pauling says a couple of good keen builders could put this boat together in a couple of weekends.

When pushed for a disadvantage, he will concede that aluminium is slightly more difficult to weld than steel; however, thanks to its simple build, the DIYNO 361 is well within the capabilities of most amateurs. Or, if you don’t wish to tackle the welding, you can tack-weld the pieces together and call in a more proficient welder to do the seams. Mostly, the DIYNO is a one-man job, but certain stages require two pairs of hands. For that reason, it’s a great father-son project.

If you have access to a press brake, some parts of the boat such as the seat or thwart, transom and girders can be folded into a three-sided, box section from one flat piece. This gives the best result but if no press brake is available, the relevant panel can be cut into three pieces and welded into a box section.

Aluminium

Pauling says thickness of 3 mm aluminium is about the practical, lower limit for amateur welding. This is heavier than would normally be used for a small boat, so the DIYNO 361 ends up on the heavy side for its length, which has in turn required a generous beam to support it. The bonus is that it is quite a big, little boat and extremely strong and stable for its size range.

The kitset arrives as two, 6.1 m x 1.8 m sheets of aluminium in a flat pack. The panels for the kitset are pre-cut within the sheet but attached by tabs at regular intervals. You can release them using a crowbar but it tends to pucker the aluminium; a jigsaw does a neater job.

The kitset comes with computer-drawn plans and comprehensive instructions. Use these to identify every part of the kitset, the length, and type of welds for different areas, and to mark out placement lines. If you still have questions, Pauling is just a phone call away.

For home handyman purposes, the DIYNO kitset includes a custom wood jig. However, when building the demonstration boat for these photos, Pauling used an aluminium jig as he wanted to use it for subsequent builds, for which he had orders. The aluminium and custom wood jigs are pretty similar in terms of setting up, but where they differ, we have illustrated the technique with photos of a custom wood Pauling built for a bigger DIYNO model. He says the custom wood jig is the easier one to set up because its pieces automatically lock in and screw together.

The jig

The boat is built the right way up, with all welds on the inside, until it is nearly complete. Then, it is turned over for welding the outsides of the seams. The jig comprises two side rails, a centrepiece, and cross members which will hold the shape of the hull. Ideally, the building area will be clean, tidy, and perfectly flat. If a flat floor is not available, set up the jig on timber bearers as you would if building a deck.

We’ll assume you have a flat floor. Use a builder’s pencil to draw a straight, centreline of at least 3.6 m—the length of the boat—on the floor. A long, aluminium off-cut will provide a straight edge. At one end of the centre line, mark out a perpendicular line using the 3, 4, 5 method to make sure the right angles are exactly 90 degrees. This is a crucial step, before continuing in the construction of the jig.

The 3, 4, 5 method uses the Theorem of Pythagoras: the sum of the square of the two sides equals the square of the hypotenuse – ie, 32 + 42 = 52. So if you measure 300 mm up from the base of the centreline, and 400 mm out from the centreline, the line joining the two should be 500 mm. If it is, you will have a perfect right angle at the aft end of your centreline.

Follow the instructions on the plan to assemble the jig from the interlocking parts. Once the jig is assembled, place it so the centreline frame is on the centreline marked on the floor and the aft frame is against the perpendicular line.

Custom wood jig

The custom wood jig is the traditional support that comes with this aluminium boat. The aluminium jig also featured in this article was made especially for the prototype of the 3.6 metre boat. The aluminium bottom panels are tack-welded to an aluminium jig and strapped down to a custom wood jig through scrap aluminium tags welded onto the hull plates.

Level

Level the jig using a dumpy level or a laser level, and a staff hooked under the three longitudinal rails to ensure it is level.

Make sure the jig is still aligned with the marks on the floor. To secure it in position, Pauling cut out timber blocks, 50 mm x 50 mm timber, and glued them to the floor with automotive filler, in position beside the lines. When the filler has set, screw the jig to the blocks. Note that the filler will form an extremely strong bond with the concrete. When the time comes to remove the blocks, it is best to chisel them off, rather than whack them off with a hammer. The filler is so strong, it will come off with a chunk of concrete.

Bottom panels

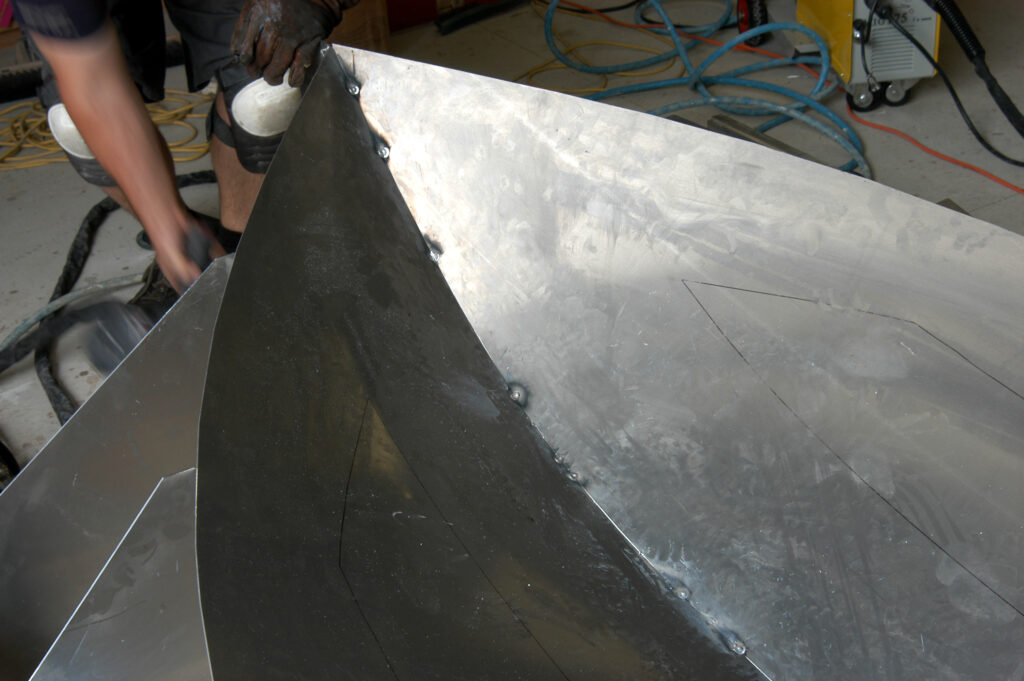

With the jig complete, it is time to start building the boat – the good news is that the most difficult part comes first: laying in the bottom panels of the hull. These panels are the boat’s planing surfaces. Pauling admits their deep-vee is more difficult to build but it gives the boat its soft, dry ride in choppy conditions, which will make the extra hours in the shed all worthwhile.

The frames on the jig match up exactly with the frames on the boat, providing easy reference points throughout the build. Obviously, this works only if the jig is set up properly at the start. The bottom panel will self-align because it has to line up with cuts for the chines on the jig.

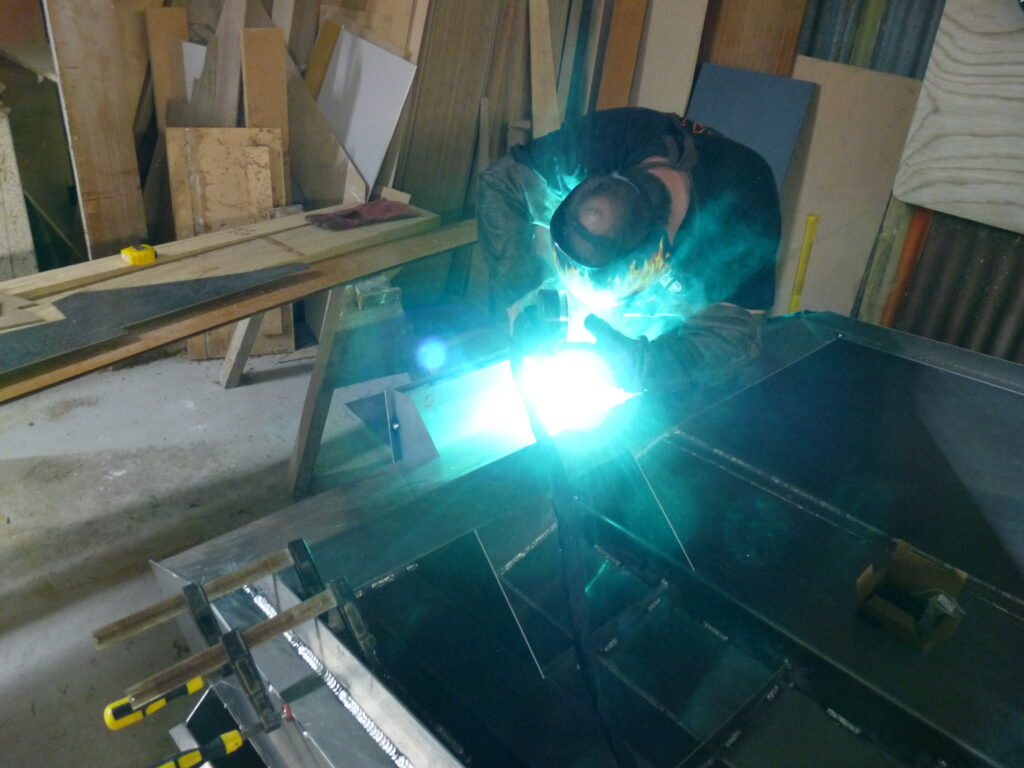

Placing the panels is definitely a two-person job. Pauling had his friend Jason Swan help man-handle the panels into position and do the welding. Do one side at a time, adhering exactly to the centreline of the jig. Begin at the transom and work your way forward, tacking as you go. The panels are conically developed but do have considerable shape in the forward sections, so it is imperative that you force the forward sections of the hull right down to the jig; this requires some grunt, so get tough and let the panels know that you’re in charge.

Pauling was using his aluminium jig, so he held the sheets in place while Swan tacked the sheets to the jig. If using the custom wood jig, cut 50 mm x 50 mm tags from the scrap aluminium and tack-weld these to the bottom panels, on the positions indicated on the plans. Use these tags to strop down the bottom panels, running the strops through the holes drilled in the jig, as shown on the plans. The tags are removed once the hull has been welded. Be aware that it may take some time to get the panels exactly right, but it is imperative that you do.

Chines, transom

The chines go on next. Pauling has designed these to overlap, rather than meet at a vee because a vee is difficult to weld. However, you will need to grind the 3mm edge of the chine into a bevel, to fit tight against the edge of the bottom panel; this will create an easy seam to weld. This is the only part of the boat where grinding should be necessary.

The next stage is to fit the transom. The transom may be folded, if you have access to a press brake, or cut and welded to shape. The key with the transom is to use temporary supports to set the transom angle as laid out in the plans for the outboard motor and to align with the topside panels.

Girders

At this stage, the boat has bottom panels, chines, and a transom but is still relying on the jig to keep it stable. Its longitudinal strength will come from the girders. These come in sections with fold lines on them; like the transom, they can be folded or cut along the fold lines and welded. The transom must be fully welded inside prior to fitting the box girders, after which the transom welds would be inaccessible.

Tack the girders in place using the pre-cut floors as spacers to locate them accurately. With the girders tacked in place and holding the shape, you can fully weld the centreline seam from the inside. Next, set the floors in their correct positions and weld off with the girders and floors.

Thwart

The thwart, or seat, is quite big but provides ample locker space and, if sealed, enough buoyancy to prevent the boat from sinking. The thwart also has the option of being folded, or cut and welded. When the thwart and transom are in place, they will support the topsides, or side panels of the boat. Note that the thwart is tacked in place initially to help set up the topside panels, but it needs to be removed to weld the topside panel to the chine under the thwart. It is a good idea to leave the thwart in place while welding the chine to the topside and only remove it to do the weld directly underneath. Weld the thwart in place when the chine-to-topside weld is complete.

Topsides

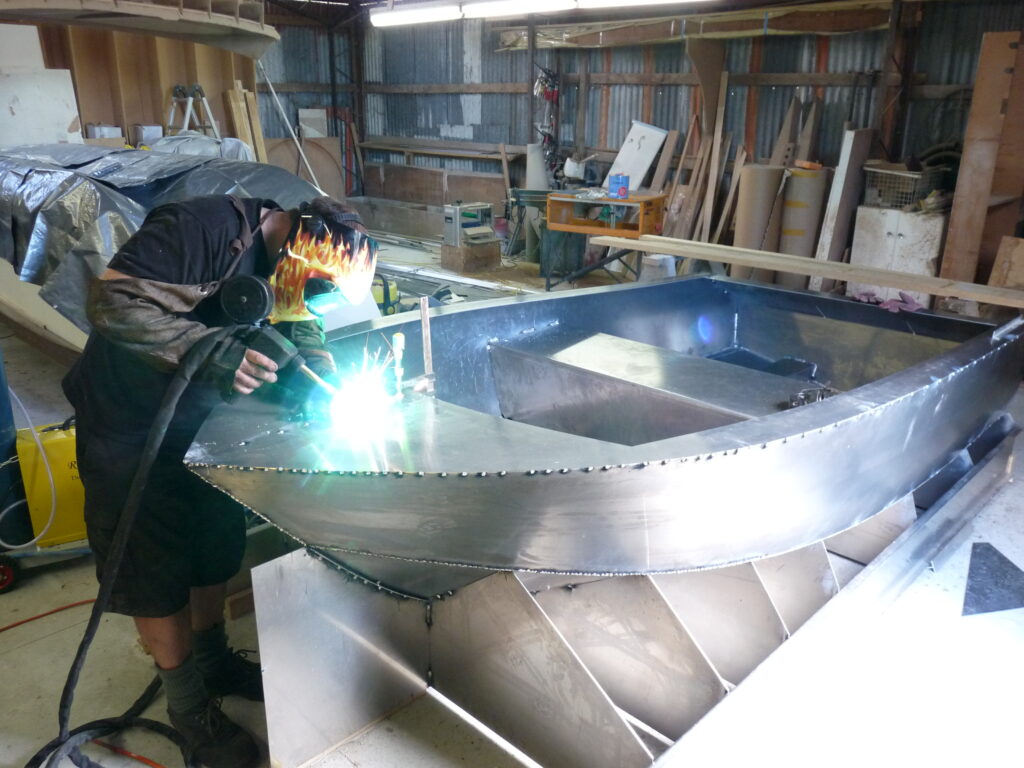

Fitting the topsides is another two-person job, as the panel has to be persuaded into place against its natural tendency to flare outwards. Start at the bow, making sure you push the edge of the topside panel hard down onto the chine so that the edges meet continuously along the whole length. Use a strop on the thwart, as shown, to bring the topside panel into near-vertical to finish snug at the transom. If the panels don’t fit at any point, grind off the tacks and start again.

“If it’s not touching,” Pauling emphasises, “don’t weld it. There must not be any gaps between components.”

Decks

When you’ve welded on the topsides, you’re ready to fit the decks. Tack the panels in place over the full length, carefully aligning the topside panels underneath. Once you are happy with the position of the decks, mark off the screen positions on the deck, according to the drawings. Tack the front screen in place at the centreline and then use the side screens to set up the angle of the front screen. Completely tack the screens in place, ensuring no gaps, before making the welds.

Finally, weld in the transom outboard bracket. Weld the T-section to the upper transom plate and then tack in the girder extensions. Weld the upper transom to the girder extensions and the boat. Stand back and admire your progress so far: you almost have a boat.

Tidying

Now comes the tidying-up phase. Turn the boat over and lay it upside down on the floor. Weld over all the seams so they are welded on both sides. You can grind welds back for neatness but they are stronger without grinding; Pauling did the gunwales and chines only. Finally, go over the whole boat with an orbital sander; this will miraculously erase ‘print-through’ marks from work on the inside so that the whole boat is a consistent sheen all over.

Once you’ve created the basic boat, you can pimp it up as much or as little as you like. Pauling made a dash out of scrap aluminium and installed a Morse kit for wheel steering; Swan is going add a thwart at the transom and tiller steer the outboard. Other options could include cutting lockers in the thwart, adding beltings, handrails, and rod holders to personalise the boat, or installing a plywood or alloy sole between the girders.

Water test

We met Pauling on the water to see how the finished DIYNO stacked up. The base boat weighs 125 kg and Pauling recommends a 25-30 hp outboard which adds another 60-80 kg, plus a 25-litre tote tank for fuel. He says it can carry a payload of 225 kg and will do 27.5 knots with 30 hp.

At 3.65m in length overall and a beam of 1.67m, the boat cuts quite a nice shape on the water from most angles. The warped vee hull form has enough angle forward to cut through the chop but softens to 12 degrees at the transom for stability; with Pauling and myself on the same side, the boat definitely heeled but settled at a stable attitude.

As Pauling put the boat through some runs and figure-eights, the chines were clearly effective in deflecting spray away from the hull, but in even a wide circle, the stern felt as though it would slide in a harder turn, due to the smaller deadrise at the transom but the trade-off is the extra stability. As Pauling points out, it is not a handling problem, just a characteristic. But, put it in perspective—you get a 12 ft (3.6 m) tinnie, safe and stable for sheltered water, that you can build over a couple of weekends for around $3300 (2010 pricing). And the satisfaction of saying you made it yourself.

Welding

Jason Swan, who also worked on the DIYNO 361 featured in this article, says a welder such as the Rilon Mig 175A is ideal for this project. It is suitable for welding in steel or aluminium, can weld thicknesses from 3mm to 7mm, and gives a smooth result. It teams well with a 250A 8m spool gun; a gun is helpful when using aluminium, which is softer than steel and therefore more difficult to push through a liner. The welder and spool gun combined cost around $1300.

Before you start, make sure the aluminium is really clean. Use a stainless steel wire brush; a standard steel brush will contaminate the weld.

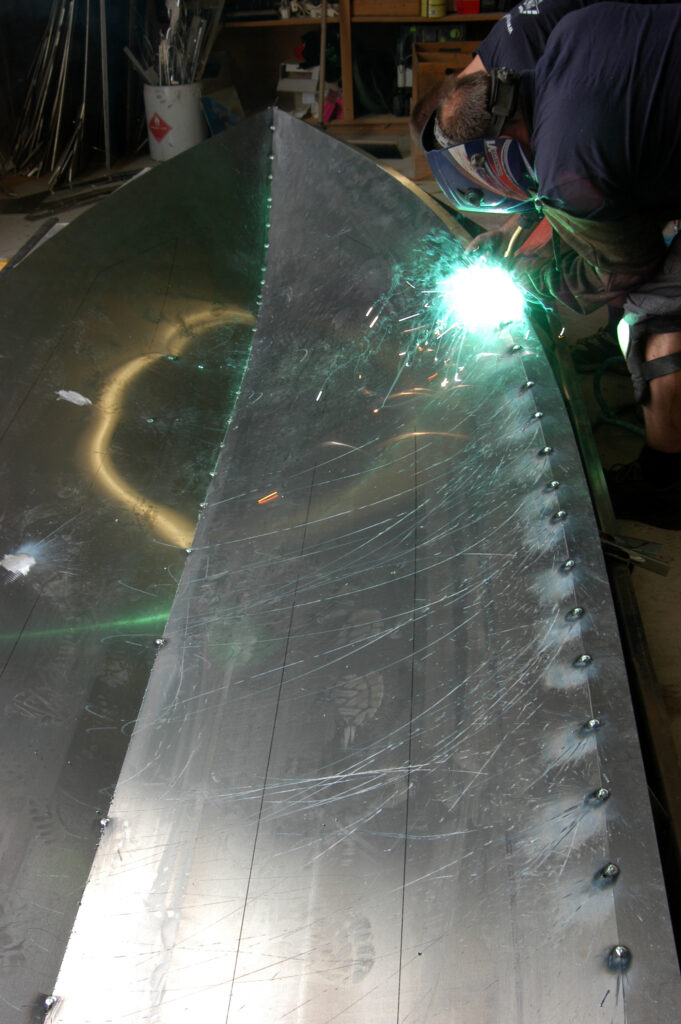

Tacks should be about 10mm apart, especially at the for’ard end of the chines where, as Swan puts it, there is little meat. Tacks at close intervals will prevent the weld blowing right through, between the panels. They also prevent the plates from moving when they heat during welding.

Refer to the welding kit for length and type of welds. Nearly all the welds in the boat are fillet welds, that is, joining two pieces together at a right angle or close to it – these are relatively easy to weld. Only a few are butt welds, where two panels meet side by side, a more difficult weld.

If you make a mistake when welding, you can grind it out and do it again, but it’s much easier to get it right the first time. Never weld if there is a gap between two panels – a 2 mm gap at one end will be 15 mm at the other end. If there is a gap between panels, it probably means the jig isn’t set up properly. Correct it, and begin again.