They say you need to make at least three bows before you can make a decent one. Raf Nathan shows how to make your first one

By Raf Nathan

Photographs: Raf Nathan

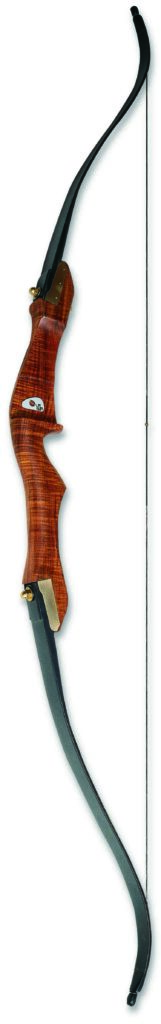

Archery is a satisfying sport that has its roots fixed in the primal skill of hunting. As a woodworker it is an added bonus that you can make at least part of your own bow yourself. A bow like the one in this project is called a recurve and consists of a handle, or riser, two limbs (the flexible parts that bend), a string and an arrow rest.

When you pull back on the string, the energy is transferred to the limbs which, on release, propel the arrow forward. Limbs are graded into poundage: beginners may use 28lb whereas the pros may be drawing up to 40lb or more. Hunting bows can go up to 60lb. This poundage represents great force which the riser must be able to withstand. This project is about my third bow – the first two broke.

Practice makes perfect

Number one was made from two pieces of blackwood laminated together. My idea was that two pieces would be more dimensionally stable than one. I used epoxy bought at a hardware store and the bow broke along the glue line. Number two was a beautiful thing made of mahogany with maple and blackwood detail veneers laminated at the middle. This bow broke purely due to wood failure. The mahogany lacked guts.

To avoid any problems with glue, number three is made from walnut because it adds cross-grain strength and look beautiful. The limbs are 34lb – any more poundage probably requires the skills of a professional bowmaker to ensure long life.

Purchase your limbs first. The international standard for archery is the imperial system, so your limbs will be 1 1/2inches wide (about 38mm). Phone around archery stores to locate one that will sell limbs separately. Buying them secondhand on Trademe is an option. Limbs of 28-30lb are a good starting point. Be warned that some people will tell you that it’s all too hard and to forget the whole thing.

The limbs sit in a pocket consisting of a shoulder on the riser and brass side pieces. The brass sides are set flush into the riser. A final thickness of 42mm for the riser, less the two thicknesses of 1.6mm brass, houses the limbs snugly.

Making the bow

Select wood clear from defects and orient the grain if possible so that it is quarter sawn with the heart side toward the face of the riser (the side facing the archer). Dress the wood square and straight. The wood should be 90mm or more in width and, say, 44mm thick. The final thickness will be 42mm (the extra 2mm is to accommodate any wood movement). Trace the pattern (see fig.1) onto the wood and bandsaw the shape, but do not saw out the shoulders where the limbs sit. You will also need to bandsaw the cut-away where the arrows rest. This is sawn full at the arrow cut-away in preparation for later routing (step 1).

Put the riser away for about a week to let the wood settle. All the sawing will release any inherent tensions in the wood and a bow or twist may develop. To re-straighten the riser skim it over a jointer and then thickness it down to 42mm thickness. Plane the edge above the shoulder square and parallel (steps 2 and 3), and then use a marking gauge to mark out the shoulder (step 4). Next, bandsaw out the shoulder (step 5).

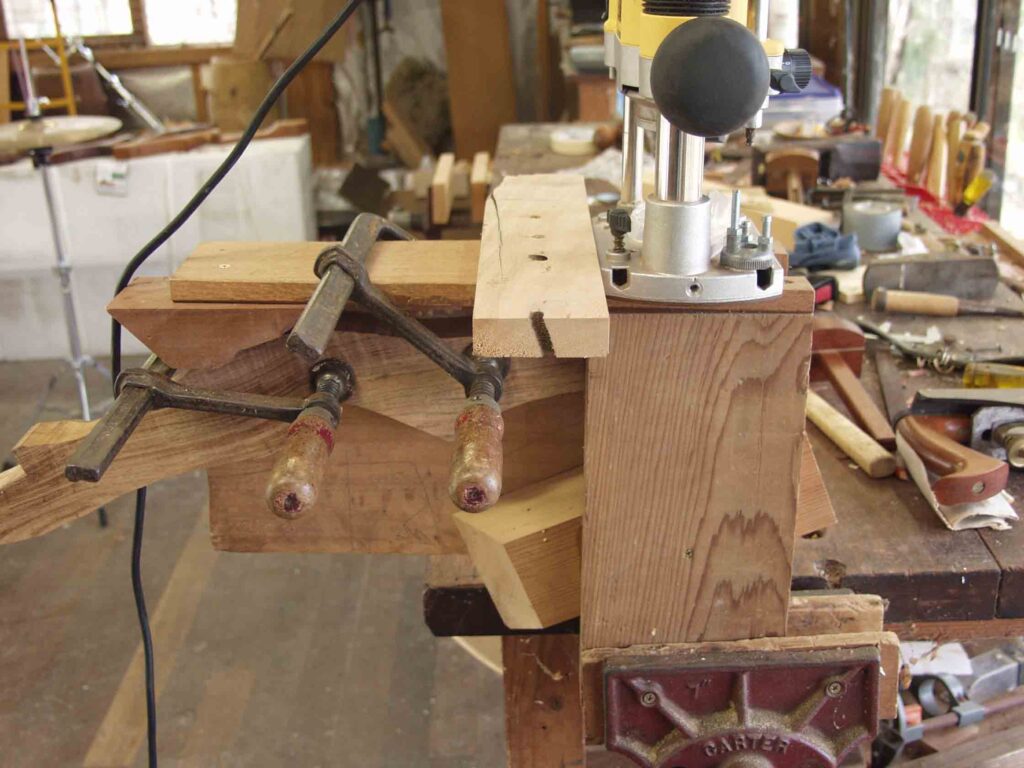

The shoulders need to be as perfectly level as possible and square to the faces. To achieve all this you can work quietly with a saw and chisel, or use a power tool and a jig. Steps 6 and 7 show a shop-made jig used to cut the shoulders with a router.

The arrow cut-away consists of a level face that ends with a lip that continues up in a sweep. The level face can also be made with a jig and router as in steps 8 and 9. The jig holds the router level and makes a clean arrow cut-away. A bowl cutter was used to rout this (step 10). Rout down deep enough so that 18mm thickness of wood remains. This should then position the arrow shaft central to the string. The sweep that continues up allows you to sight the arrow when it is mounted. A bowl cutter is a flat-bottom bit with radiused corners.

Shaping

Now begins the actual shaping of the riser. This requires sanders, chisels, spokeshaves, and patience. Step11 shows a belt sander reversed and the front drum being used to shape the hand grip. Using a rounding-over bit in the router and running this over some of the edges can speed things up. A spokeshave is of great value for refining lines, as is a scraper. An inflatable sanding bobbin is absolutely invaluable for this type of work, but not essential – just a lot faster. Try to refine the shape as much as possible before starting hand sanding. Use 80-grit paper followed by 100 and 120 grit.

At this stage the holes for the limbs can be drilled. The holes need to be exactly centred. Mark a centre line on the shoulder, then hold the limbs in place and mark where the holes need to be. In this case a horizontal mortising table was used for the drilling with a 9.5mm (3/8inch) bit.

Now the brass sides can be fitted. The action of the sides is to position the limbs parallel to the riser. The brassware (Step 12) was prepared by a local engineer. He was presented with a drawing and the shapes were cut with a metal router. The holes for the 4 square drive screws were drilled and countersunk, and a sink with an 82° angle was used to ensure a tight fit with the screw heads.

Set your drill press to allow the screw heads to protrude slightly; they will sand back flush to the plates later. Hold the brass plates in position and mark out the shape with a scriber. A laminate trimmer with a flat-bottom bit can remove most of the waste and, importantly, keep the surface flat and level. Before routing set the cutter depth to the thickness of the brass. Pre-drill the holes and fit steel screws first, remove them and replace with brass screws.

The hard walnut can break soft brass screws and removing broken screws is a hassle. Without the use of specially made brass sides an easier but more simplistic way to align the limbs would be to have the riser at 38mm (1 1/2inch) thickness so the limbs were flush with the sides. Small, shaped pieces of wood could then be fixed at the sides to form pockets for the limbs.

Sanding and polishing

The brass sides can then be sanded level with the wood with a belt sander. Now the whole piece must be hand sanded up to at least 320 grit. Polishing comes next and the choice of finish is optional. A bow will be used outdoors hence a water-resistant polish is best – oil, lacquer and oil/shellac/varnish mixtures can work well.

Now the limbs can be fitted. I sprayed the original white limbs shown with a black enamel. Brass bolts with dome heads and washers have been used in this piece, but stainless steel is another option.

At this stage it is time to visit an archery store for help with a string and arrow rest. Strings and rests are inexpensive and the store will be able to recommend what to use. They can fit the rest and set up the bow, matching arrows to suit your bow and personal draw length.

A bow, like a gun, is shot, hence it can be a dangerous implement so sensible and supervised use is critical. A novice will benefit from joining a club to learn correct technique and, more importantly, safe shooting practices.