Making hand tools of highest quality

Chris Vesper is an Australian tool maker who has enormous respect for his ancient craft. I met him at the Timber and Working with Wood Show in Sydney earlier this year. He makes some of the highest quality tools available anywhere in the world, working from a large shed on his parent’s property in semirural Victoria. Mankind first developed implements from wood, stone and other natural fibres in at least 100,000 BC and Chris Vesper continues the evolution by taking woodworking marking tools to a new level. As an 18-year-old he found himself without funds to buy tools to further his woodworking passion, so he started making his own. That was 12 years ago and for the last nine years he has been a fulltime toolmaker, the two years he spent as an apprentice fitter and turner giving him basic engineering skills. He has developed a philosophy to produce “quality with no compromises” while enjoying using very good, older machine tools which he completely reconditions before adding them to his workshop. “There are no cheap Chinese machine tools in my workshop,” he says with pride. As a small manufacturer, to sell his tools Chris relies heavily on his stands at the various Australian woodworking shows and on his website. He says shows are a great way to talk to people about his products although they can be expensive in travel and freight costs and in time away from his workshop. From his website, about 40 percent of his direct sales are to the United States and Europe.

Reconditioned

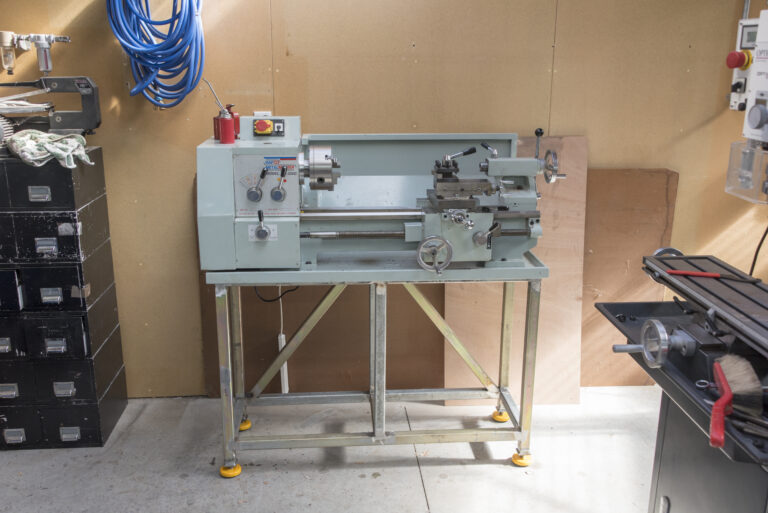

The first machine he refurbished was a very old, large band saw that he still uses every day. He now has two surface grinders, precision tool-room lathes, mills and other machines you would expect to find in a precision, engineering shop. He works on his own, making every aspect of every tool. He sees every part of what he does as a way of life, has no debt and thoroughly enjoys making woodworking tools in a cottage-industry setting using traditional machinery. He does remember getting sick of working for other people and wanting to have a go on his own, even though in the early days he recalls being down to his last $5. He has come a long way.

Signature tools

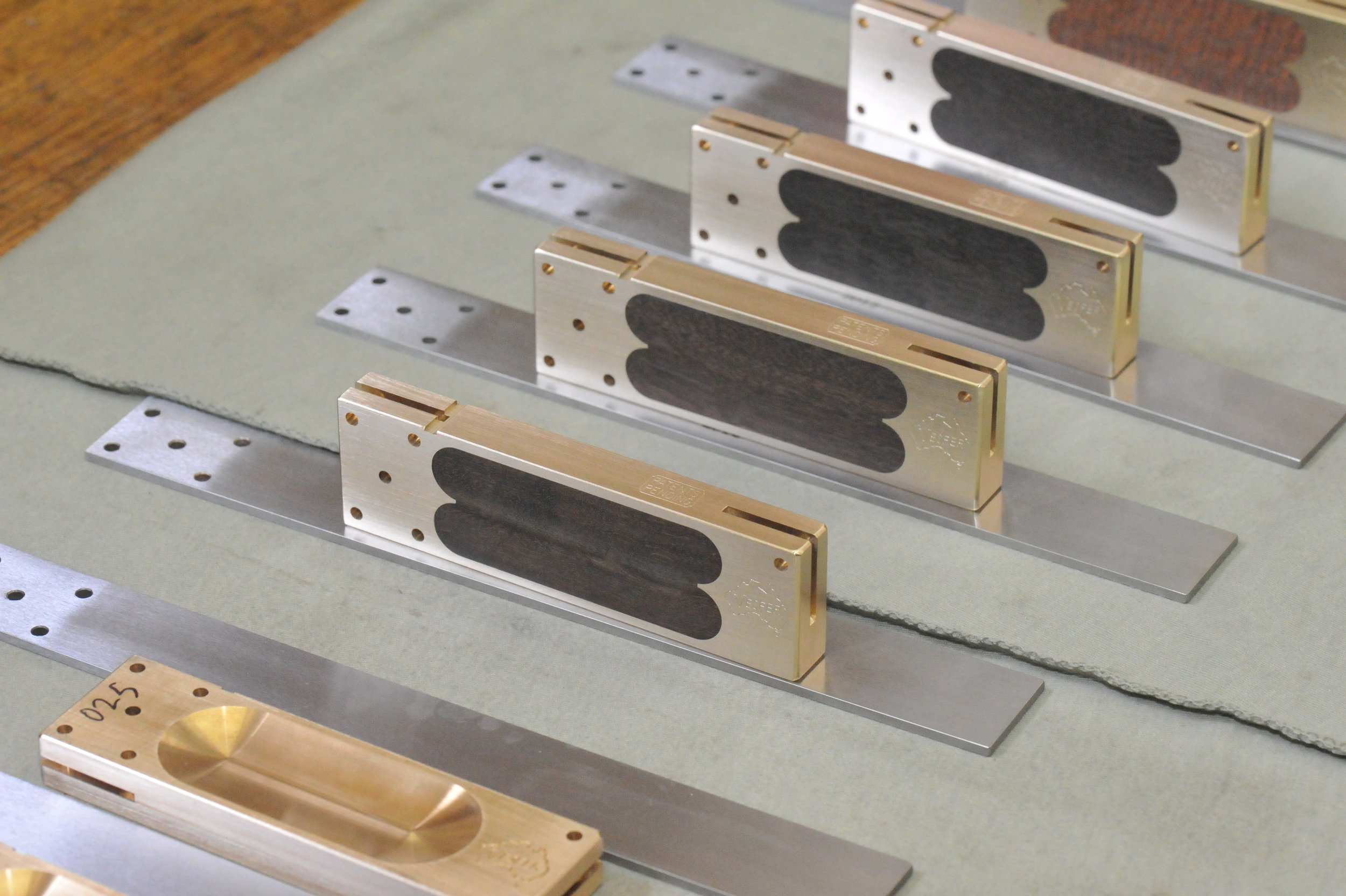

While he makes different marking-out tools, he considers his signature tools his precision double square and his sliding bevels. “I am the only guy in Australia making sliding bevels,” he says with much pride. His double squares are of hardened steel, precision-ground and are really more akin to metal-working squares. But, Chris says, “woodworkers just love using them and they remain one of my big sellers. I market these as accurate to .001 of an inch over the length of the blade but in reality they are accurate to about .0002 of an inch.” The ergonomically designed try squares are available in three sizes—4”, 7” & 10”—and the inlay models use Australian timbers such as Tasmanian Blackwood. The blades are manufactured from 400 series stainless steel.

Detailed

His manufacturing process is very detailed. The blades are first lasercut from stainless steel sheet, roughmachined, hardened and then precisionground on all edges. The blade and stock are held together by pins and the holes in the blade and in the stock for these are drilled separately, not with the two pieces clamped together. This indicates the accuracy of the drilling and reaming required. Machining accuracy is paramount for the brass stock of the try squares and for the timber inlay—Chris hand-fits this without getting any oil on the timber. The sliding bevel blades are made using a similar process to the try squares and are also available in three sizes—4”, 7” and 10”—with highest of three levels being the inlaid models that require more time to manufacture. The sliding bevels tighten into place with a unique locking mechanism and stay fixed, obviously a requirement of the tool but one which many cheaper brands fail to achieve. The marking gauges and marking knives in the rest of Chris Vesper’s tool range exhibit the same quality as his other tools As Chris Vesper makes every component himself, his production is limited by the number of hours in a day and he is now at maximum capacity. The labour content of each tool is very high and he says there are simply not the margins to allow him to employ staff. He also is keen to maintain his lifestyle, using traditional machinetools. And where does he want to go with his tools? He says he feels he is already there, making tools of the highest possible quality with no compromises. All of us need some sort of outlet other than wall-to-wall work and Chris finds this in a surprise sort of way. His outlet is ballroom and Salsa dancing. He says working long hours in the workshop requires intense concentration and “after the hard-nosed technical ability of making fine tools, dancing gives me the freedom. I would be in a straightjacket if I did not have this outlet”.