Words and Photos: Jude Woodside

As the saying goes, there are only two certainties; death and taxes. While we can do little about the latter, we can at least be prepared for the former. That is the motivation behind the group that gathers every Wednesday in a former warehouse in Rotorua. By 8.00am on a clear Rotorua morning, the carpark is beginning to fill up and the doors to the former warehouse are opened. People are moving trestles. Drop sheets are spread and large boxes are carried out carefully and set up on the trestles. Paintbrushes are readied. From within comes the familiar whine of power tools.

The Kiwi Coffin Club, self-described makers of fine underground furniture, is open for business.

Established in 2010, the club has grown from four members to having more than 40 at present. The primary aim is for each member to make and decorate their coffin. The coffins cost around $240 including handles and plastic lining. Decoration is up to the owner. The cost includes a small donation to the local Hospice. The club is the brainchild of Katie Williams a former midwife, district nurse and hospice nurse, someone who has experienced all the stages of life for herself. It was originally a club of the University of the Third Age (U3A) an organisation that aims to maintain the love of learning in people after retirement. But recently the club has gone its own way as it was seen as a service organisation which is outside the remit of U3A.

Decorated

As Katie explained, “It was four people who wanted to build their own coffin, personalise it, be in control to the very last moment…as Pakehas we don’t grieve very well-stiff upper lip-Mum’s not going to die, Dad’s not going to die and (the club) has brought families together because they see Mum and Dad are so relaxed about it they’ve had great enjoyment doing their own thing.”

For the most part, the coffins are decorated to re ect the pastimes or lifetimes of their occupants. This has included some truly imaginative examples like that of Raewynne Latemore who has adorned her casket as a shrine to Elvis. Her coffin is also adorned with the emblem of the caravan association, presumably for her final journey. One member attached the back pocket of his jeans to the end of his coffin declaring “Who says you can’t take it with you.” He intends that his wallet will accompany him.

Members take the completed coffins home where they are used as furniture.

“We’ve got them being used as bookshelves,” says Katie. “One lady’s got hers as a dressing table—she’s covered it over. The most glamorous use was a family that had two coffins; they had a big stereo in the lounge with coffins standing up at either end of it, with wine racks in the top half and speakers in the bottom half.”

Control

Katie sees the club as a means of people taking control over their funeral arrangements and at the same time eliminating the mystique and the reluctance to discuss the inevitable. The club also provides “bucket books” (for when you “kick the bucket”) to allow for every aspect of the funeral to be sorted. They include a section on “Skeletons in the closet” for those that might need to unburden themselves (in their absence) in the interests of family history.

The original venue was Katie’s carport but congestion in the street and noise as the club grew eventually forced them to find other premises. Joe La Grouw, who founded Lockwood homes, and his wife Jo-anne offered to help and donated the club’s current premises. The club pays the cost of electricity.

Grown

Numbers have grown, largely spread by word of mouth, and the club is currently producing up to three coffins a week. By May this year they had made 30 and expect to double that before the end of the year. There are two styles of coffin—the traditional six-sided one or a rectangular casket. In addition to the adult coffins, the club also produce coffins for stillbirths that they donate to Rotorua hospital.

“We do four sizes from about 20-week foetuses up to full-term stillbirths. We line them and we give them away free. They store them up at the hospital and when someone loses a baby they are offered one of our coffins. We got through quite a few and we were surprised that there were that many. “Before they used to put them in a cardboard box or a bag, but now they have the opportunity of having a proper little box, a bit of dignity. It certainly helps with the grieving process because it’s a real coffin not a plastic bag,” Katie Williams says.

“We enjoy the fact that we can give back to the community. It gets (the members) out of bed and gets them going. We also build ashes boxes to give to the hospice. So many of them have been touched by the help they get from the hospice with their wives or their husbands.”

Templates

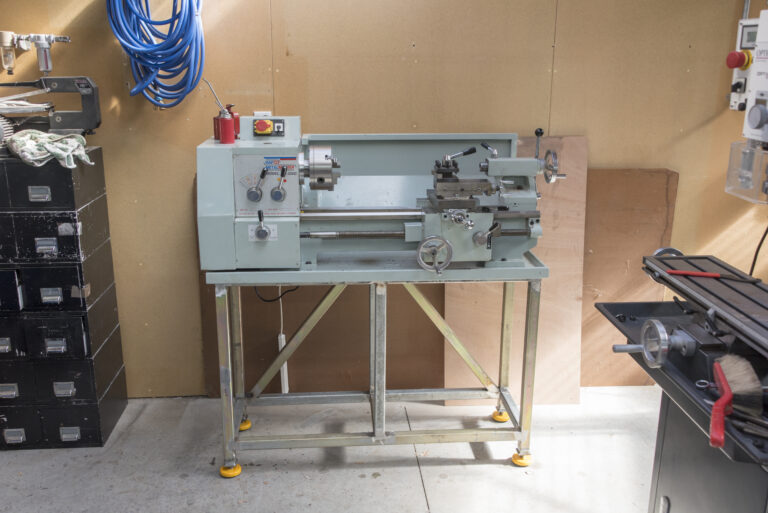

In the workshop, Bruce McPike and his regular band of helpers is busy preparing another coffin. Bruce, a former joiner, created the coffin designs and he has made a series of templates to make the process easier. “We have four sizes. They vary in length mostly. We can get two coffins from three sheets of 16 mm-thick MDF.”

Bruce has sketched out the top and bottom templates and cuts out the shape roughly with a circular saw. Once cut, the template is clamped to the piece again and routed to shape with a flush-cut bit. The sides are cut on a table saw to 300 mm. For the traditional-style coffin, the sides are bent to form the shoulder region.

The side is kerfed. This involves a series of cuts that penetrate only of the way through the board and allow the board to be bent without breaking. The kerfing is done with a special jig that Bruce and his team have developed that includes a right angle with markings to determine where the 16 saw cuts should go.

Cuts

There are specially marked cuts that don’t traverse the board completely, leaving a solid gap at either end of the cut. These cuts are made as a plunge cut. This is an element of the design that arose from experience. Once the kerfed section is bent, it is covered with another thinner piece of MDF that is bent to the same curve and screwed and glued in place. The blank sections allow the screws to hold; previously the gaps were too small to allow them to hold properly.

Once the kerfs are made, Bruce uses a template made from steel to pre-drill the screw holes in the sides where they will screw to the base. At this point it is important to remember which side is which, to ensure the holes go in the correct sides. The ends are attached to the base piece, then the side is placed in another jig where the base can be mated to it. The jig allows the sides to be curved gently and gradually screwed to the base for support.

After the base and sides are screwed together, the reinforcing pieces for the kerfed section are clamped in place with special formers that another member with engineering skill has created. The formers are attached with clamps that conform the reinforcing to the curve where it is screwed into place. The ends of the sides that protrude past the ends of the coffin are cut square— first by hand with a saw and then planed and sanded flush. The top edge is also planed and sanded flush at this stage.

Lid

The lid is placed on the coffin and aligned with a 16 mm overhang all round. The coffin shape is then marked on the top by running a pencil around the box. With the lid turned over, the holes for the screws that will hold it in place eventually are marked.

Adjacent to each hole, a block is attached to locate the lid in place. Applying a small amount of glue and rubbing the block back and forth in place until the glue gets tacky fixes these in place.

The lid can now be finished with an ogee bit to provide an ogee or S-shaped moulding on the edge as decoration. The screw holes are filled and sanded smooth. All that remains is to add the handles. There are two styles of handle available:

-

the traditional style that looks like metal but is in fact chrome-plated plastic; or

-

wooden handles made in the club.

To ensure that the handles are consistent, templates make the job easy. The coffins are then provided to new members to be lined and fitted out and painted or decorated according to their owner’s wishes or imagination. The Kiwi Coffin Club is still growing with new members every week. An offshoot is being established in Tauranga. The local Maori community has also had its attention drawn by the activity of the coffin club, with one local marae starting its own group and others expressing interest.