Casting bronze is a young sculptor’s passion

By Roger Lacey

Photographs, Geoff Osborne

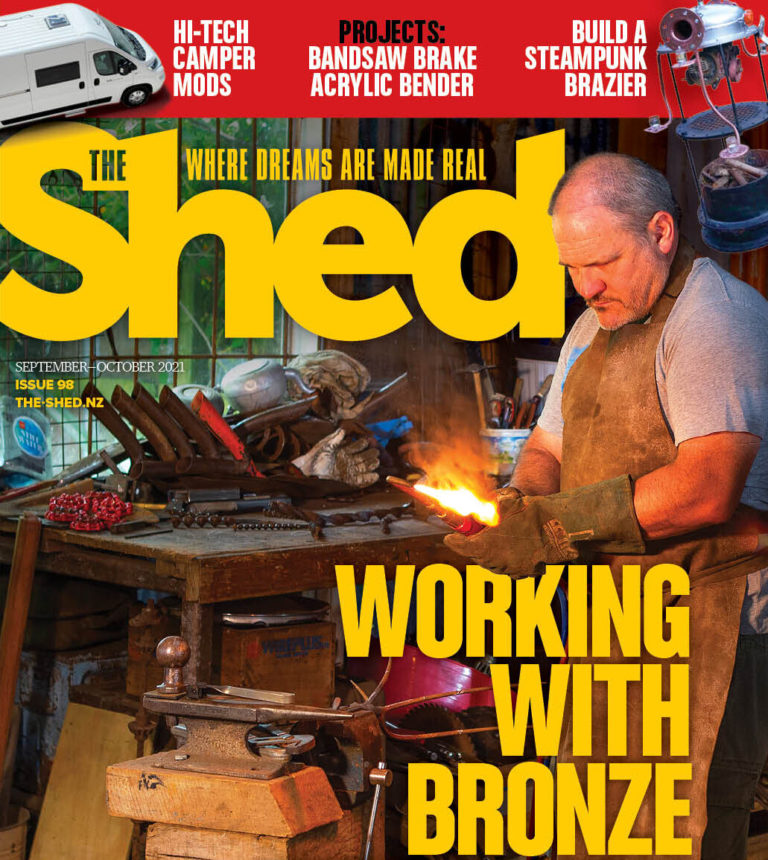

Above: Rudi Buchanan-Strewe at work in his studio. Part of his motorbike collection is in the background.

Nestled in a fold of land, high above Karekare Beach on Auckland’s West Coast, is a wooden house with a collection of small outbuildings. This remote location with the Tasman Sea as its backdrop is the home and studio of artist Dean Buchanan, jeweller Helga Strewe and their son Rudi Buchanan-Strewe.

Dean and Helga are established and renowned artists in their own right, however our visit today is to talk to Rudi and watch him casting bronze.

Brought up in a family of artists, Rudi has tried to break the mould and, after work experience as a blacksmith, he completed a motorcycle apprenticeship at Classic Cycles in Upper Hutt. A move back to Auckland saw him working for Ken McIntosh on his Manx Nortons before deciding, about eight years ago, to give in to his genes and pursue his love of sculpture.

Home sweet home with the Tasman Sea as a backdrop

Australian diggers—Rudi’s early bronze sculptures.

Self-taught

Rudi specialises in bronze casting and hand-beaten copper work. He is self-taught but has had plenty of help from artist friends and advice from his casting suppliers. Much of his learning has been through experimentation, trying different brasses and bronzes and various mould materials to get the results he wants.

There have been a few lessons along the way—one pour he made into a mould that was not quire cured resulted in the mould ejecting a fountain of hot bronze which hit the ceiling and rained down on him. Although he was wearing protective equipment, one small piece landed behind his ear giving him a painful burn and some valuable knowledge.

His moulds are made from a mixture of plaster of Paris and molochite (a processed kaolin clay). Experimentation has given him a recipe that works well for his purposes. “Foundries usually keep their plaster recipes a closely guarded secret,” he says.

He mixes up a slurry that he coats the wax with, trying to avoid trapping any air bubbles. Carefully he builds up the coating in layers, making sure not to let it dry out between coats. To make sure the mould is strong enough to support the weight of the molten bronze, the plaster usually ends up at least 50 mm thick.

For a successful pour, the most important process is to cure the mould properly. It takes seven days to heat the plaster to more 800°C and bake out the chemically bonded water. It is an expensive exercise with a typical batch using around 90kg of LPG.

Rudi made his kiln from a 44-gallon drum

The kiln in action.

Drum kiln

Rudi has made his own kiln out of a 44-gallon drum and he packs as many moulds into it as possible for each firing. The kiln is starting to rust so Rudi has a new, larger one under construction. The kiln sits in its own three-sided shed. The moulds are put in upside down and when heated the wax melts and runs out. “It smells really bad when it’s cooking,” Rudi says. Always experimenting, Rudi shows me a leek and some chicken feet he has cast in bronze. “I just made the plaster mould around them and the heat of the kiln turned everything inside to carbon.”

Most of his castings start with a hand-carved wax model. If he wants to produce a series of near identical castings, Rudi casts a silicone rubber mould around the original then pours the wax into it. He shows a mould of Alice that is part of a series of characters he is making from the book Alice in Wonderland.

“Complex shapes like this can be difficult,” he explains, “I’ve sometimes got to break it out in parts then put it back together.” He has a work-table with a gas burner and a large selection of tools for carving, shaping and smoothing the wax.

Along with Alice, he has made the Mad Hatter and the White Rabbit. The Caterpillar, who sits on a mushroom smoking a hookah, is next in line. To prepare the wax for casting, Rudi has to attach wax runners to all the dead ends and high spots to make sure the molten metal flows smoothly through the mould and traps no air. The metal is poured into a sprue which is made large enough to provide a molten reservoir where the bronze can be drawn from as the metal cools and shrinks. This reduces the internal stresses in the casting.

The soldiers were made from a mould

For near identical castings Rudi casts a silicone rubber mould around the original wax model

Metal workshop

Rudi’s workshop extends across several buildings; the metal workshop is in a small tin shed with an earth floor. A miniature home-made forge sits in one corner with an anvil beside it. The bench opposite is where Rudi does his fettling and his hand-beaten copper work. A delicate copper vine is a current work in progress.

At the back of the shed is the casting area. All Rudi’s equipment is home-made: the furnace is made from a cast-iron water pipe joiner and the burner used to melt the bronze is his own design, refined by experimentation. The tongs he uses to hold and tip the casting crucible have all been made using his blacksmithing skills.

The furnace has provided a background roar while Rudi has shown us around his other workshop areas. The first ingot has melted and the small tin shed is roasting hot inside.

Wax carving tools

Rudi’s miniature hand-made forge

Alice and the Mad Hatter with three hand-beaten copper shrimps in the background

Hot mould

A mould, still hot from the kiln, is propped up ready for the pour. “Some people bury the mould in sand to help support it and stop it from cracking but I make the mould strong enough to get away with doing it like this,” he comments.

With all his tools and protective equipment in place, Rudi acts quickly, lifting the lid off the furnace and scraping out any impurities off the surface of the liquid bronze. Grabbing the crucible with a pair of specially designed tongs, he places it inside a steel ring with a long handle that is then used to lift and tip the bright orange molten bronze into the mould.

Work in progress—a delicate copper vine

Home-made equipment: the cast-iron water pipe joiner furnace and tongs

There is no great shower of sparks, bubbling or (thankfully) hissing of steam, the bright orange plug at the top of the mould quickly dulls while Rudi gets on with readying his next batch. The crucible is placed back in the furnace, another ingot added to it and the lid replaced.

The bronze needs to cool for a while before Rudi can attack the mould with a hammer to reveal whether all his work has produced a successful casting. “It is brittle when it is too hot,” he notes.

Once the casting has been broken out of its mould, the sprue and runners are cut off and the casting marks ground and polished off. If required he drills and taps a thread into the base for mounting. To finish the bronze he can use various potions to achieve different affects. Colours can vary from black to a deep bronze sheen to a teal-coloured verdigris. Treating then polishing the high spots brings out the delicate patterns carved into the original wax.

Above: Heating the bronze and then scraping out any impurities off the surface of the liquid bronze.

Beginning to pour the liquid bronze…

L to R: …into the mould made from plaster of Paris and molochite. Placing the crucible back in the furnace… …and adding another ingot.

Exhibitions

Rudi has the odd exhibition in galleries around Auckland. He has sold some pieces but says it is hard to make a living with bronze casting as his material costs and the amount of labour are so high.

“I reckon I made about $30 a day,” he says with a wry smile. “A 7kg ingot of silicone bronze costs around $100, plus there’s all the gas to melt it and also to cure the moulds.”

Rudi has seen cheap imported bronze work selling for less per kilo than he can buy the material for but it is a very inferior bronze. “I’ve tried casting red brass [also known as gunmetal] but it gives off a lot of nasty fumes and doesn’t pour nicely,” he comments.

From a shelf Rudi takes down and shows me his 2011 TCAC Emerging Artist award-winning entry, Horse Power. It is a beautiful hand-cranked automata of 12 cast-bronze horses moved by a Buick V6 camshaft.

Rudi gets great satisfaction from his casting and he has a growing reputation as an artist with pieces being sent around the world. Working in such a beautiful location surrounded by his parents and wife, Sayaka, it is an enviable lifestyle that he obviously loves. While the financial rewards may not be great, being able to work the hours you choose on something you love in such an inspiring environment is beyond value.

Attacking the mould with a hammer…

…reveals the casting…

…has been a success

Bikes and Model T

Rudi’s wax-working studio also houses a collection of motorbikes and his 1927 Model T Ford powered by a flathead V8 that he has been working on for seven years. “It started as a pile of rusty bits,” he says. “I started working on the chassis in my bedroom, tack-welding it together over oven trays filled with water then dragging it outside to finish the welds.” He also cast an aluminium twin-carb manifold for it but has since found and fitted an original single carburettor.