Tired tools and discarded parts are reinvented

as works of art

By Sue Allison

Photographs: Juliet Nicholas

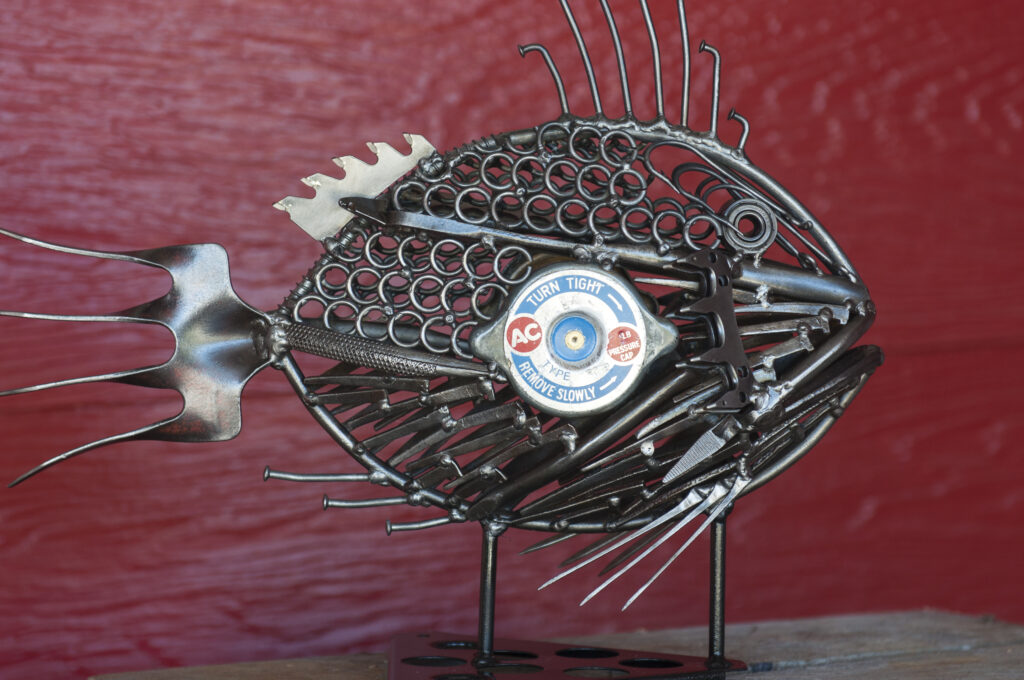

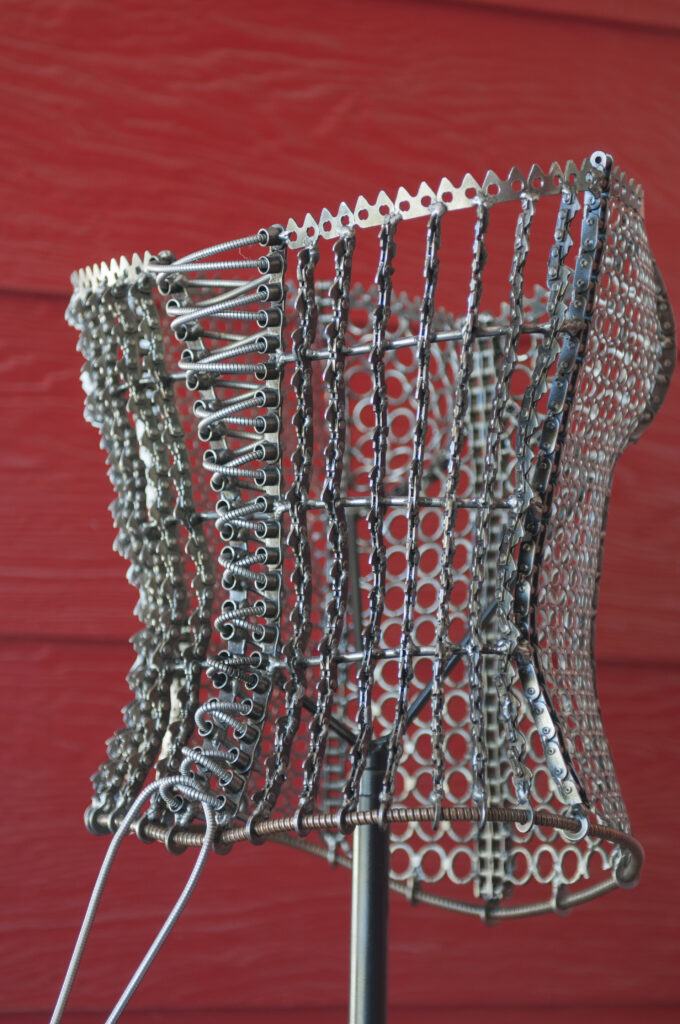

Broken blades, tired tools, worn washers, grimy gears. These are sorry sights for most sheddies, but for Bruce Derrett they are the treasures of his trade. The Motueka metal artist combines his skill wielding a MIG welder with a highly fertile imagination to turn other people’s junk into quirky creatures, funky furniture, and striking sculptures.

Bruce, who ironically failed metal work at school, has always had an eye for mechanical bits and pieces. “As a kid I was always pulling things apart, like clocks and radios. It used to really frustrate my mum,” he says. Now he puts things back together again, albeit it in a very different form.

Bruce’s full-time foray into the art world is a relatively recent venture. He left school at 14 and, until four years ago, he and his partner of 25 years, Jocelyn White, earned their living working on orchards and dairy farms while raising three children. Along the way, Bruce taught himself the art of gas metal arc welding and tinkered in his spare time making metal creations and selling them at the Nelson Saturday market.

It was Jocelyn who urged him to turn his artistry into a full-time job. “She’s my biggest fan,” says Bruce. “We worked hard and got rid of the mortgage and one day she just said, ‘You’ve got to go home and give it a go’.” He agreed to try it out for one year and has never looked back.

While he sells smaller pieces at the World of Wearable Art (WOW) museum and supplies a couple of shops, the weekend market is still his main outlet.

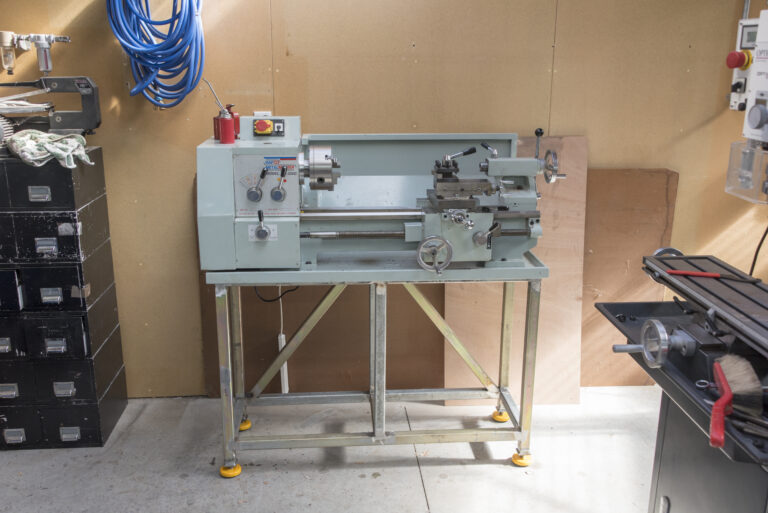

Bruce makes his metal sculptures in a double garage attached to the house. “It isn’t ideal. I’d love a big shed, of course. What guy wouldn’t?” He has lined the interior walls with corrugated iron to reduce the fire risk and made all his own steel work benches. “Everything is on wheels so I can take them all outside if I need my garage to work on a trailer or something,” he says.

“It isn’t ideal. I’d love a big shed, of course. What guy wouldn’t?”

Parts department

It is a highly organised workshop, despite containing huge quantities of paraphernalia waiting in the ‘parts department’.

“You have to be organised or you would never find anything,” says Bruce, who separates bolts and bearings into boxes of different sizes, hangs lengths of chain from a post and has ladders around the walls to reach materials stored in the ceiling space.

“I don’t waste much,” he says. “I use everything except aluminium, even the cut-off pieces unless they are too rubbishy or thin to weld.”

Bruce’s penchant for old tools extends to ones that still work. “Most of my tools are second hand. When I started out I couldn’t afford new ones, and the old ones are often better anyway.” He picked up both his drill press and a grinder at garage sales, and still uses the bench grinder he bought 23 years ago when he was 20.

Preparing the pieces for welding can be as time-consuming as the construction process. Bruce has to dismantle the old machinery and clean all the pieces. For extra-grimy parts, he has invented his own washing machine, tumbling them in a concrete mixer filled with gravel and water. “It makes a big racket for the neighbours, but it cleans off a lot of the rust and grease.” A final scrub is done with a wire brush fitting on a grinder. “My MIG welder doesn’t like rust. You’ve got to clean up all the spanners and bolts before you can weld them.”

“They like to see things being reused rather than going to the dump”

Garage sales

Bruce makes plaster of Paris moulds for some of his forms, such as his half-wood, half-metal bowls. As with table tops, he has to lie the pieces face down so the finished surface will be flat. This makes visualising the end result all the harder as he can’t see the full effect until it has been welded together.

While Bruce often spends more than 40 hours a week working on his sculptures. He enjoys the freedom of setting his own hours, often working into the night or taking time off to scour garage sales for raw materials.

Friends know where to bring their broken tools and appliances, and people drop off bits and pieces at the market. “They like to see things being reused rather than going to the dump,” says Bruce, whose stall always attracts curious people exclaiming as they recognise components in his creations. “People love looking to see what things are made of. Old garden tools are good because people can really relate to them, but they are getting harder to find.”

While Bruce makes standard lines through popular demand, no two pieces are ever the same. “I’m brewing ideas all the time,” he says. “It works both ways. I either have a design in my head or look at a piece and see what it will make.” He sees a bird’s body in a petrol can, scorpion tails in broken darts, a miniature bird cage in a wire cake mixer. “If you see those bits in a box in someone’s shed, it’s just junk, but I can change it into something people appreciate,” he says, mulling over a box of kitchen discards. “It’s not smart technology. It’s just giving old stuff a new life.”

Cube table

Bruce was in the process of making a modern coffee table in metal decorated with sprocket inserts when The Shed visited.

Bruce welded six half-metre square sheets of steel together to form a cube.

He lays out the different sized sprockets, most of which came from motorbikes, then marks their positions with a pen.

He cuts the circles using a plasma cutter. Bruce made his own “compass” jig out of wire and a magnet. The magnet sits at the centre of the circle with the other end of the wire attached to his cutting tool at the length of the radius. “It’s too hard to cut a perfect circle free hand,” he says.

The sprockets are welded into position and then he cleans up the welds.

This trendy coffee table is now in an apartment in Melbourne.