Gary Sarten…fixing kids’ bikes for free.

Fond childhood memories drive a passion for giving kids the freedom of having their own wheels.

Many people of the baby boomer generation will recall the freedom kids had in days gone by. You hopped on your bike and headed off to find your mates to explore and have fun. Building huts, playing cowboys and Indians, forming gangs, co making bows and arrows, playing war games, catching tadpoles, climbing trees—the only rule was to be home in time for dinner. The world was there to enjoy and bruises and injuries were all part of the action. Gary Sarten’s fond memories of those days are something he wants to pass on to today’s kids and he believes an important part of those days was having your own bike. Now semi-retired, 63-year-old Gary lives in the house where he was raised

One of Gary’s tandems.

“I was pretty excited but a bit gutted as it was a girl’s bike. Dad and I then found a boy’s bike.”

in rural Taranaki and he spends a lot of time repairing bikes to give to kids so that they can have the freedom he enjoyed in his childhood. Gary is known locally as “The Bike Dude” and he’s been doing this for a while. There are second and third generations of kids out there riding bikes Gary has renewed. His years of fixing and supplying bikes free to kids who had no wheels were recently recognised with his nomination in the Community Spirit category of the Pride of New Zealand Awards.

Part of Gary’s collection of recycled bikes, including a couple of unicycles.

Rebuilding bikes

He fixes and rebuilds bikes of all sizes, as well as scooters—for no cost—just for the pleasure of knowing the enjoyment the new owners will get from them. Gary has a workshop, once a walk-through milking shed, full of bike parts and tools, plus a number of smaller sheds that surround his house on his two-acre (0.89 ha) property, crammed with bike bits and bikes that have been re-built waiting for a new life. He was aged nine when his father gave him his first bike. “I was pretty excited but a bit gutted as it was a girl’s bike. Dad and I then found a boy’s bike at the Lepperton dump and we did it up. I suppose that’s where it all started.” For a long time Gary sourced his frames and bike parts from the local dumps. “I introduced my son to dump rummaging. It’s fun. Now the New Plymouth and Waitara Transfer Station and Just Rubbish Waitara put aside bikes and parts for me. “We are used to being a throw-away society and many of the bikes that get dumped only have one wheel damaged.” Gary said most of the bikes he resurrects go to Waitara children. When he gets too many he gives them to the Waitara Corso shop.

A steering wheel instead of handle bars!

Part of the frame of a modern kid’s trike. “Some of these new bikes are rubbish and just snap in two—the metal is more like tinfoil.”

Quality control

“Some bikes and trikes on sale today shouldn’t be on the market. The steel is like tinfoil. There are some that are okay compared with the old bikes but some are absolute crap, they are disposable, like many things today. Some new bikes just snap in half.

Gary and one of his sheds full of bikes and parts. Note the lean to on the lean to on the lean to.

“In the old days bikes were passed down through a family. Now there’s planned obsolescence.”

“I can’t understand why they sell some mountain bikes today that have a sticker saying ‘not designed for off road use’. That’s pretty ironic. “Scooters are an exception. Many of those built today are pretty solid. Compared with those made during the big scooter craze of the 1950s, the new ones are stronger and kids give them a really hard time. “In the old days bikes were passed down through a family. Now there’s planned obsolescence and some of the bikes are lucky to last one kid. “It’s a bit tragic that many kids don’t get taught to look after their bikes these days. Many of the bikes I get have parts that are frozen with rust from not being put away at night or not having their chains lubricated. “A lot of people don’t get around to lubricating bikes. I use CRC or WORX on the chains.” Some of the old bikes have enclosed bearings that stop the water from getting in. Gary prefers back pedal brakes and said they are more reliable and there’s no cables to worry about.

“I’m giving away around 100 bikes a year at present.”

A car bonnet has a new lease of life as part of a wheelbarrow.

“I couldn’t imagine life as a kid without a bike and the freedom it gave me.”

One of Gary’s projects—rebuilding a 1928/30 Chrysler 66 sedan.

Production line

“It’s a different world today. In days gone by the bike was a means of transport, especially if you couldn’t afford a car. Now bikes are mostly for leisure or fitness. “However a lot of people are struggling financially these days. “I’ve amped up production over the last few years and I’m giving away around 100 bikes a year at present.” He showed us his glass house full of bikes ready for new homes. “I guess the bike business has taken over the horticultural business,” he says with a grin. Gary was raised on the family dairy farm and was a home appliance serviceman until appliances stopped being repairable. He is also a semi-retired, award winning wine maker (he spent 12 years at Sentry Hill Winery making fruit wines) and has done various building, landscaping and horticultural jobs. “I’ve always had this bike thing going though. I couldn’t imagine life as a kid without a bike and the freedom it gave me.”

The Akrad Flyer—a solid trike.

Bullets to trikes

Beating swords into ploughshares or ploughshares into swords is an old concept reflecting different times. The pedals and seats of the Akrad Flyer trikes made after World War II were made of recast aluminium from army surplus bullet tips. During and after the war Akrad Flyer trikes like these were made by a firm in Waihi called Auckland Radio. When the line was finally closed in 1969, about 200,000 had been made and Tonka Toys then bought that part of the business, running it for five years.

Pedals and seats were made from aluminium bullet tips

surplus from World War II.

In 1974 the Akrad Flyer returned to Waihi when Brown and Brown (Waihi) took over production for a further 10 years. Both firms had made about 10,000 trikes a year, so from 1945 to 1984 approximately 300,000 Akrad Flyers had been turned out. These trikes were solid and made to last and many baby boomers will recognise them from their childhoods. His stand for holding the bikes while he works on them is hard case. The base of it is an umbrella stand and the clamp is from a scaffolding unit. It does the trick though. He has a potbellied stove warming up the shed.

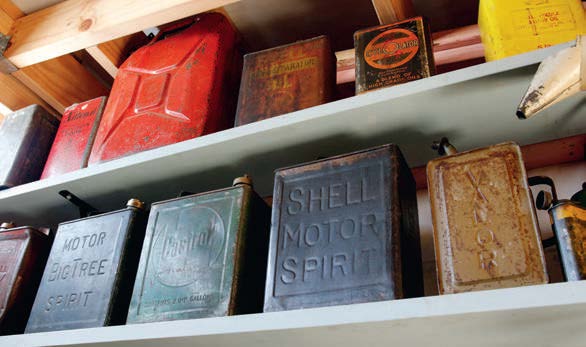

One of Gary’s many collections: old metal oil containers

Unusual bikes

Gary’s wife Charmaine runs after-school care and holiday programmes for kids through the Anglican Church. To tie in with this the couple have a shed full of interesting bikes— two-wheelers, tandems and even unicycles and scooters for these kids to have fun on. Included are some crazy bikes and a few that have steering wheels instead of handle bars. Two old Raleigh 20s have been welded together to make a tandem. “That’s my Raleigh 40,” says Gary. One of his sheds has a big collection including old trikes, many of which are solidly made and have lasted 75 years or so. He said bike fashions are recurring. “The chopper bikes for kids are back in fashion and oldstyle Raleigh 20s for adults, some complete with baskets, are back on the market.” Gary is also a collector. Like any self-respecting eccentric he has collections in all directions—old valve radios, fishing rods, old heaters and clocks, blowlamps, gramophones. You name it. One of his other projects is to rebuild a 1928/30 Chrysler 66 sedan. He has a chassis and some rusty parts but no picture of the car. The chassis is laid out ready to go. At present bikes take up a lot of Gary’s time. As well as repairing bikes Gary also gets given working bikes that are no longer needed. He wants to thank people who have given these. “The biggest buzz I get is when I’m down town and I see a kid going hard on, say, an orange bike with a green wheel and I know that’s one of mine I put together, and there’s a kid having fun on it.” Gary doesn’t want any payment for his bike repair jobs, but the word is out that he’s a big fan of ginger crunch!