Getting around in style

If there’s one sort of person that cannot resist a challenge that’s a Kiwi backyard inventor. When a mate sent Dave Hunger an internet photo of a giant wheeled contraption and a challenge to reproduce it, Dave rose to the task.

The inventive Stratford dairy farmer is no stranger to The Shed. Readers may recall Dave’s giant trebuchet with 13 metre-long throwing arm (“Man who gives a toss,” Dec 2010/Jan 2011) and this year Dave’s full-sized working replica of Henry Ford’s first tractor was featured (“The first tractor,” Oct/Nov).

Now parked alongside his Taranaki milking shed is his latest machine—his Spring project—a giant pedal-driven two wheeled device that really defies description. The machine took a month to put together.

Two 2.6 metre-high spoked wheels tower over a seating platform where two people provide pedal power to drive the machine along. At the back is a small seat for Dave’s grandson.

Wheels

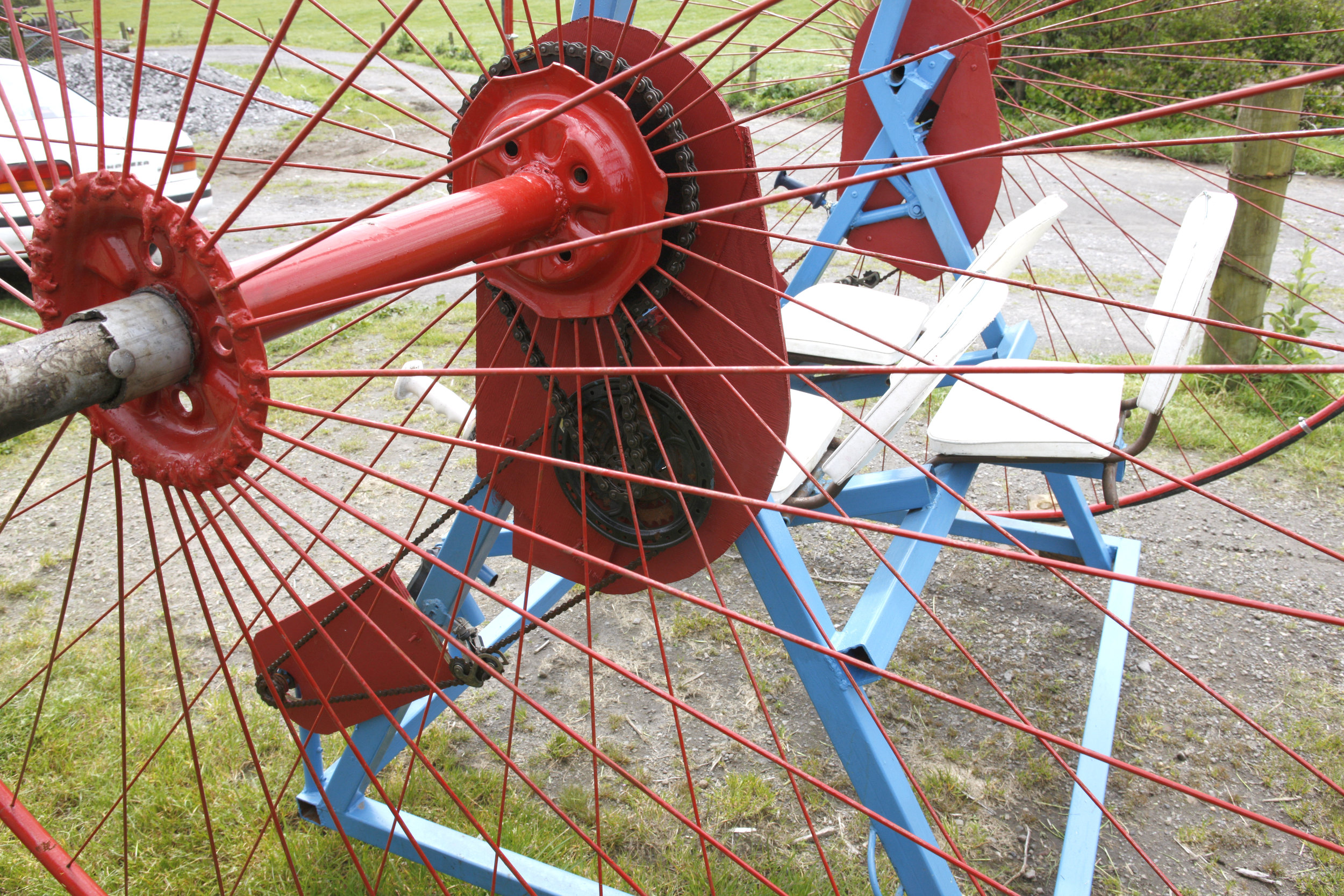

Dave made the wheels first. That was the hardest part. Each wheel has 60 spokes, made from 4 mm mild steel rods which took many hours to fashion and thread.

“I had to spot-weld the nuts where the spokes are attached to the rim. They kept popping off. There is a lot of pressure on them. It took all afternoon just to do that.”

The axles are 500 mm wide. Dave said the bigger the wheel, the wider the hub diameter needs to be for strength.

The axles are 40 mm water pipe welded onto the cut-out centres of car wheel rims and spinning inside 50 mm pipe on the outside. There are no bearings; the space between the pipes is packed with grease.

The wheel rims are made from 1 inch (25 mm) water pipe which Dave cut lengthwise in half with an angle grinder. Before bending this pipe around a water trough to get the big arc, he drilled the spoke holes in it on his drill press.

The tyres are made from 1 inch (25 mm) rubber milking tube, attached to the rim with hose clips.

Gearing

Four old bicycle cranks from the scrap-metal yard support the pedals which chain-drive the wheels.

“I had to gear it down to make is easier to pedal. It took a bit of figuring out,” said Dave.

There’s a 4-1 ratio to the first sprocket, driven though a bicycle chain, and another 4-1 ratio drive to the final cog which is driven by a motorbike sprocket and chain. He put bicycle chain tensioners in-line to keep the chains tight.

The free-swinging seating platform is made from 50 mm box steel. Dave picked up his three “retro” seats from the Salvation Army Thrift shop for $2 each.

He said the original photo he worked off showed the big wheels on a difficult angle to get measurements from, but he estimates his machine is within 150 mm of the American model.

Big Wheel

What do you call this machine? we asked Dave.

“That’s the 64 thousand dollar question. It has no name. I call it my Big Wheel for now. I’m looking for a name—any suggestions welcome.”

Dave was to enter the machine in the Stratford and Inglewood Christmas parades where it was going to be sure to turn a few heads.

You need to be reasonably fit to pedal the Big Wheel. Steering is basic. One person pedals harder than the other to turn a corner.

We took the machine onto the road for a photo and the first vehicle to come along was a cop car. He stopped, wondering if he was seeing things. After muttering about safety he gave a grin and drove off. No arrests were made.

Dave’s farm is full of unique games and inventions he has created for kids. There’s a bicycle driven roundabout, a giant see-saw and crazy bikes of all sizes.

He has even constructed a 10m x 25m maze, made of shade cloth and black plastic.

For the big kids he has sheds full of antique farm machines. He is a keen member of the Taranaki Vintage Machinery Club, and on display are antique bulldozers and old tractors and machinery. His farm is an attraction for visitors to the annual Taranaki Fringe Garden Festival.

Dave’s inventions are everywhere you look on his farm. He is a keen member of the Taranaki Vintage Machinery Club, and as well as sheds full of old machines such as antique bulldozers, he has a bicycle-driven roundabout, a giant see-saw and crazy home-made bicycles of all sizes, including a penny farthing bike.

He has even constructed a ten-metre x 25-metre maze for kids, made of shade cloth and black plastic.

High time

One of Dave’s home-made bikes is 2.6 metres high. After seeing a YouTube clip of a guy riding a tall bike with three front wheels, one above the other, Dave decided to go one better. “I thought I’d take it to the limit and five wheels should work,” he said.

This was Dave’s winter project. He extended the front forks with galvanised water pipe and welded brackets in line for the five 16-inch (406 mm) BMX wheels, one above the other. You pedal the top wheel and this friction-drives the others through the tyres to the driving wheel. There is a 26-inch (660 mm) wheel on the back.

“The bike parts are all from the scrapyard. It was a bit tricky to weld it together with the thin bike parts and the water pipe. I had to turn the arc welder down really low. I used 3.2 mm 68A rods and just spot-welded the joins. It’s not too hard to pedal, I was quite surprised. The main trouble is you are very high off the ground. It’s a long way to fall.”

Dave put a small seat on the back for his three-year old grandson. “He likes the bike but luckily he isn’t that silly to sit behind granddad at that height,” said Dave with a grin.

This bike won’t be in the Christmas parade. “There are no brakes and you have to keep moving,” said Dave.

He entered his penny farthing bike in a previous Christmas parade in Stratford but ran into grief when a clown in front of him stopped to distribute lollies. Dave stopped too and fell off. “Sometimes we learn the hard way,” he said.