E-BIKES ARE IN THEIR INFANCY IN NEW ZEALAND BUT KIWI DESIGNERS ARE KEEPING UP WITH THE WORLD TRENDS.

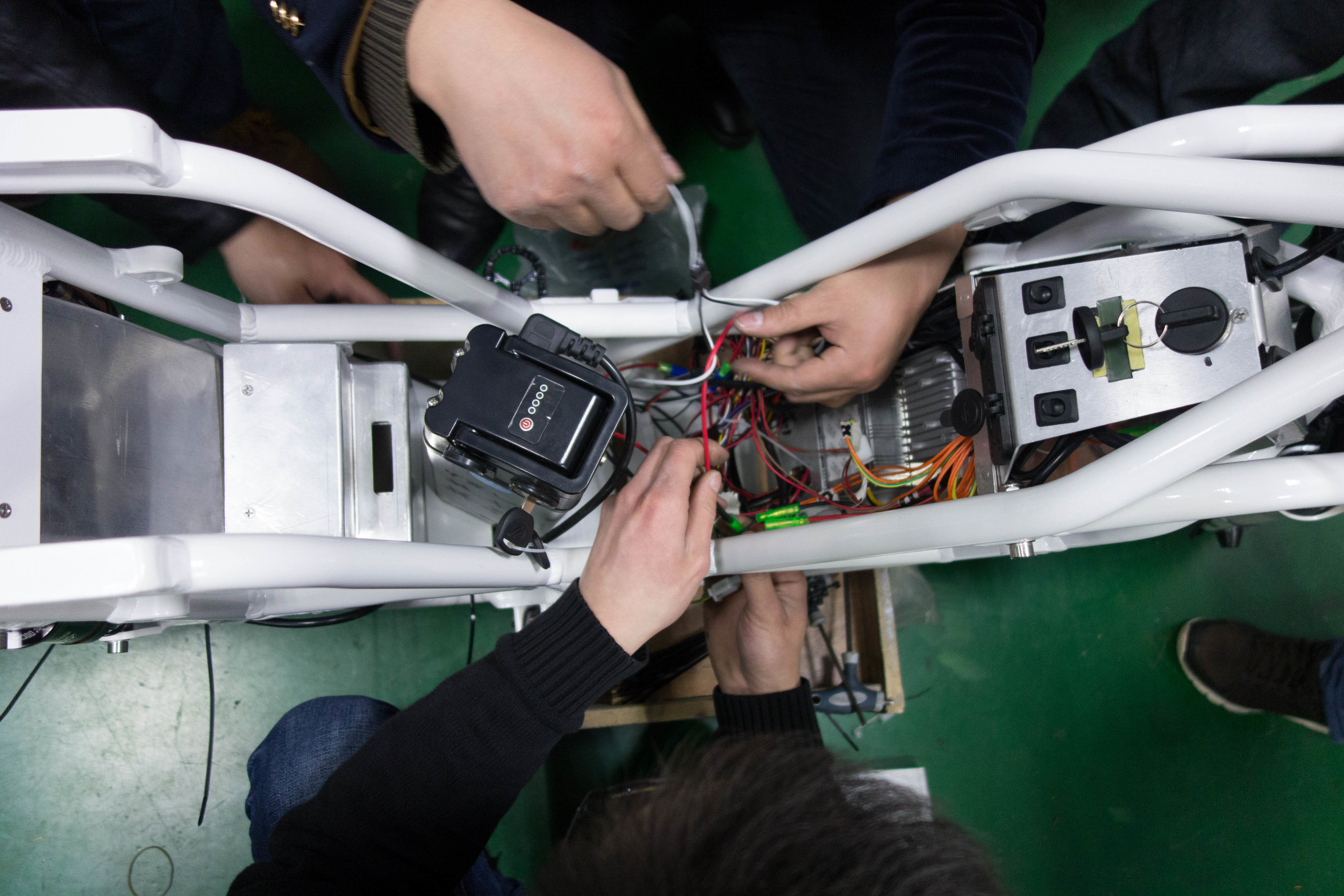

New Zealand has been slow to adopt the electric bike revolution that is sweeping the globe but a couple of keen Kiwis (and a Canadian) are using their ingenuity to create e-bikes with a difference. Anthony Clyde has had a varied background that included an unfinished degree in product development, importing semi-precious jewellery from India and writing a script for a short film that was selected for the Sundance Film Festival. In 2005 he had a dream about making electric bikes and has been focused on them ever since. He initially started importing e-bike conversion kits from other manufacturers but was having some reliability problems with them. While at a bike fair in Australia he met John Shaw from Timaru-based Reiker Cycles who was tendering for the supply of e-bikes for New Zealand Post. They collaborated and built an initial run of 60 bikes for trials. The feedback from the posties helped them to refine the design. “The posties’ bikes get an incredibly hard life,” says Anthony. “They are used every day in all weathers along with constant starting and stopping.” Improvements were made to the cabling and battery case to make them more rugged and easier to swap out parts for repairs. With the lessons learned from the postie bikes and good manufacturing contacts in China, Anthony designed and now sells his own SmartMotion e-bikes throughout New Zealand and in five overseas markets.

E-farm bike

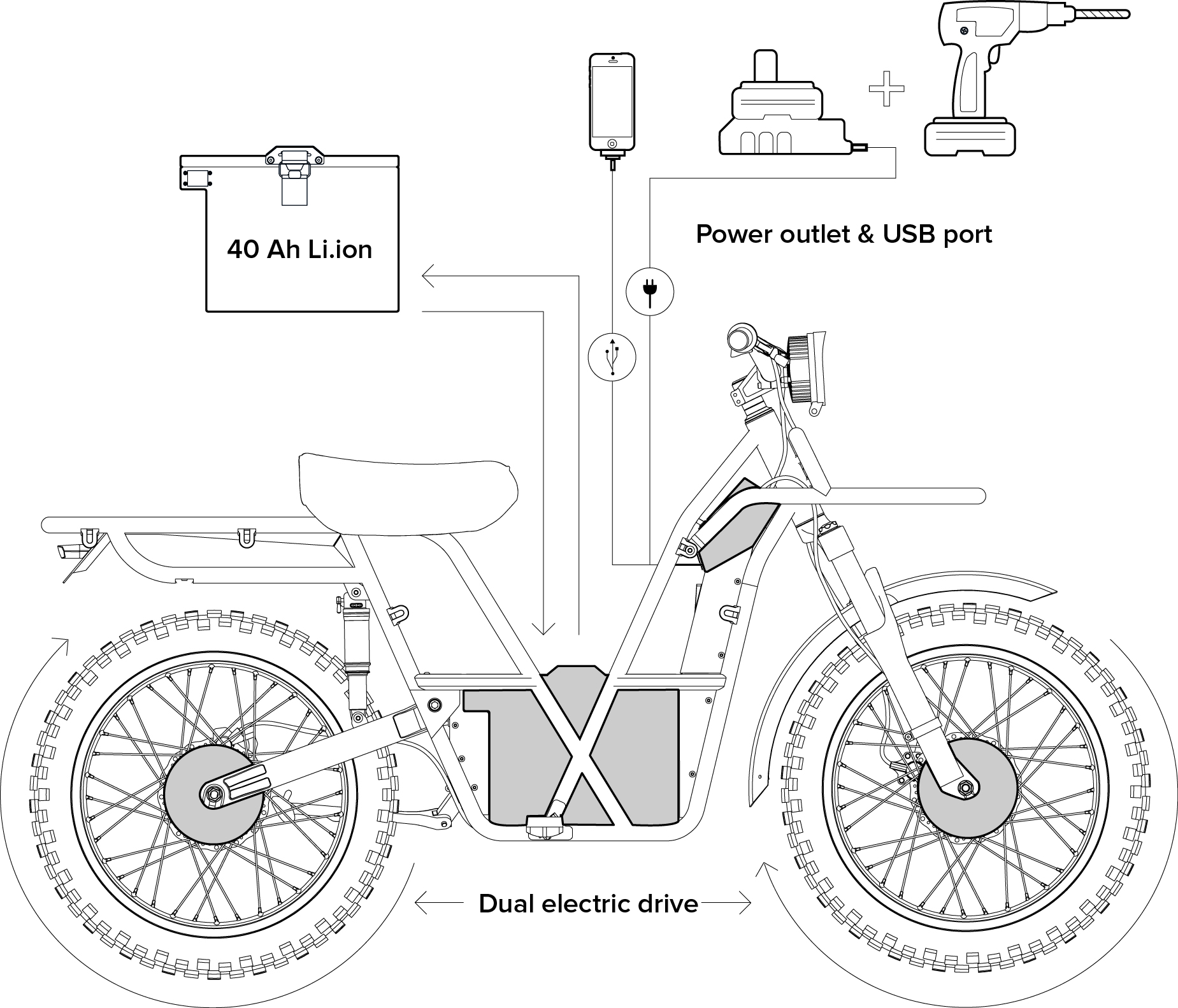

Around 18 months ago, Anthony teamed up with Daryl Neal, an industrial design consultant and e-bike enthusiast who runs Wellington Electric Bikes. Daryl had previously helped Anthony with his SmartMotion bikes and has his own brand of e-bike conversion kits he sells under the Lekkie brand. Together they came up with the idea of developing an e-farm bike and showing it at the 2014 Mystery Creek Feildays. Looking at the calendar they saw they only had six weeks but they managed to get a prototype built just in time. The bike picked up two of the three award categories available to them in the Fieldays Innovation Awards. The prizes helped them accelerate development, marketing and production with the first production run due in time for the 2015 Fieldays. Initially named the Steed, it is now called the Ubco Utility Bike and features two-wheel drive from motors in both the front and rear hubs. Weighing 50kg and able to travel up to 100km on around 60 cents of electricity, the bike comes with charging ports for both a phone and battery powered tools. Two-wheel drive gives the bike excellent traction and hillclimbing ability. The bike has attracted interest not just from farmers but also hunters and emergency services. St Johns Ambulance has tested one with a specially designed stretcher. With a 70 per cent growth in e-bike sales last year and an untapped off-road market, both Anthony and Daryl are excited about the future.

Eureka moment

Canadian Howard Stone was living in Christchurch when the earthquakes struck. He found that his e-bike was a great way to get around the broken city until he got to the badly damaged parts. Flying through the air after hitting a particularly bad crack in Hagley Park one evening, he had the thought that an off-road e-bike might have helped avoid the pain he was about to experience. A short time later while on holiday in California, he saw bikes with fat tyres being ridden up and down steps and along Venice Beach and he had his eureka moment. The soft, wide tyres coped easily with the sand and gave the bike a comfortable ride over the steps— all they needed was an electric motor and they would be perfect for Christchurch. It took five years of development and finding reliable suppliers in China to refine his current range of bikes sold under the RYOT brand name. “One early batch of motors I got ran backwards,” Howard says laughing. His products have been well tested and he tells of a customer who was riding up in the hills around Arthur’s Pass during a torrential rainstorm. “His phone drowned, his GPS drowned, but his bike kept going.” The street-legal bikes have a 300- watt brushless motor in the front hub and a seven-speed derailleur on the back giving them human/electric 2WD. With battery, they weigh around 33kg all up and the low top tube allows riders to step through the frame rather than swing their leg over. “I wanted a bike that could be ridden by anyone. My first customer was a 75-year-old man,” Howard says proudly. The steel frame means they are easily repaired or modified. “I’ve seen them with gun racks and surfboard racks welded on them,” he explains.

Best batteries

Howard is not after making the most technically advanced bikes and is the first to admit they are built to a price. However there is one area he does not compromise on: “I won’t sell cheap batteries, we only use Sony batteries that are good for 1500 cycles.” He regards cheap batteries that are under-powered and last barely a few hundred cycles as not only giving e-bikes a bad reputation but as a waste of precious resources. He has developed 750 and 1000- watt off-road bikes but his latest project and one he is most excited about is proportional regenerative braking— using the motor to recharge the battery while slowing down. He has a patent on his “go & slow” throttle design and sees this as the way of the future for urban e-bikes, giving them around 25 per cent extra range. Howard is certainly not stuck for ideas; he is also working on an e-bike and solar-charging package and sees a huge market for it in developing countries or disaster areas. He also supplies DIY kits for people who want to design and electrify their own bikes. With the e-bike market in its infancy in New Zealand, Howard has seen plenty of e-bikes that have been dropped into the market by people who have imported only a few. His latest shipment of 200 bikes has been mostly sold and he is committed to providing long-term support. Howard has also helped out Burnside High School, supplying them with some of his prototype frames, wheels and plenty of parts for them to build their own e-bikes and e-trikes for the high schools’ EVolocity competition. Next on Howard’s list is building a grid-tied, solar-powered house. He will be installing the newly announced Tesla Powerwall battery as a way of smoothing demand, using cheap nightrate power to top up any solar shortfall. But that is another story.